The subject of African Americans fighting for the South tends to generate two polar responses: either it’s a neo-Confederate fantasy with no more legitimacy than Holocaust denial, or it’s a historical reality that politically correct academic historians are conspiring to hide because it contradicts their interpretation of the war. The problems with the second response are legion, starting with the fact it assumes academic historians could agree on anything, much less a universal conspiracy to violate their professional duty to follow the evidence wherever it leads. The first response has a problem of its own, however, in that there exists at least anecdotal evidence of occasional black participation in combat for the Confederacy.

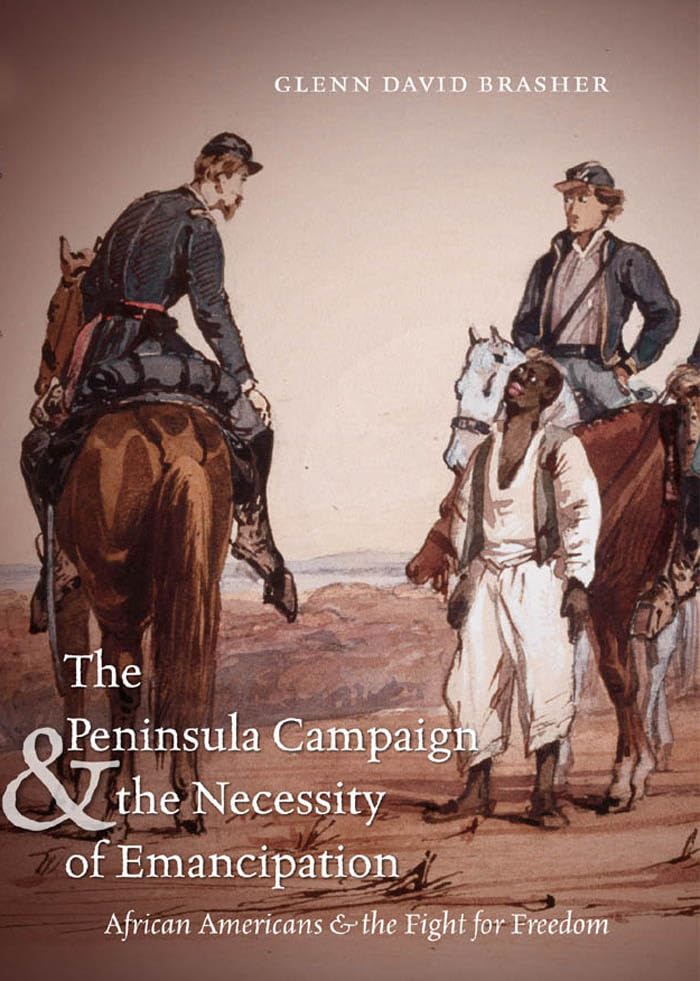

No serious historian accepts the idea that many thousands of black southerners voluntarily fought for a society that held them and their families in bondage, but how does one reconcile this with the contemporary accounts of northern soldiers and newspaper correspondents that mention southern use of armed African Americans? Glenn David Brasher brilliantly breaks the impasse between these two views and advances the argument beyond “Were there any black Confederates?” to analyzing the meanings that both sides attached to the idea of black Confederates. He shows that enslaved and free African Americans contributed substantially (but not voluntarily) to the military effort of the Confederacy in the Peninsula Campaign, and even more crucially to that of the Union, and that their involvement on both sides was critical in moving the northern public toward emancipation in 1862.

The Virginia Peninsula was the scene of interaction between slaves and Union soldiers from the beginning of the war. Brasher demonstrates how the process that led to emancipation began there, and how contingent it was on the actions of individuals, including the first enslaved people who sought refuge at Fort Monroe, the soldiers they encountered, and of course Major General Benjamin Butler, whose decision to treat them as “contraband of war” set the pattern for other Union commanders. Brasher details the influence that the intersactions of slaves and soldiers had on northern war aims, which in 1861 did not include emancipation. The extensive use of slaves to build Confederate entrenchments, and reports (accurate or not) of slaves coerced into fighting against the Union, were cited repeatedly by abolitionists as reasons why the army should employ escaped slaves as laborers, if not as soldiers, and why Congress should pass the First and Second Confiscation Acts. At the same time, Union soldiers came to value the services of African Americans who could guide them through the swamps and forests of the Peninsula, inform them about Confederate positions, and relieve them of fatigue duty digging trenches in the hot Virginia sun. Although their commander George McClellan was determined to dodge the question of slavery and to fight only to restore the Union as it was, Brasher shows how the troops on the ground came to feel otherwise by midsummer 1862. The “military necessity” argument for retaining escaped slaves and putting them to work, instead of allowing the Confederates to take advantage of their labor, was so strong that even conservative, anti-abolition newspapers like the Chicago Times eventually accepted it. Lincoln’s decision in July 1862 to issue the Emancipation Proclamation (as soon as the military situation permitted) fits seamlessly into Brasher’s argument that the actions of African Americans during the Peninsula Campaign, particularly the use of their labor by both armies, played a critical role in the evolution of emancipation as a war aim.

This book does what history does at its best. It starts with an argument that has hardened into fixed positions (“Were there any black Confederates?”) and revisits the evidence in order to move beyond the original issue and redirect our attention to a larger, equally polarized, and more important historical question, that of who freed the slaves. Brasher shows how emancipation evolved from the actions of many parties, starting with the enslaved people of the Peninsula, but significantly including the officers and men of the Union and Confederate armies, the slaveholders of Virginia, radical Republicans in the Senate, Abraham Lincoln, and the northern public as a whole. The Peninsula Campaign may have been a defeat for the Army of the Potomac, but the author concludes that it was a decisive victory for African Americans, whose emancipation would not likely have come about in 1862 had McClellan taken Richmond and ended the war.

As for the “black Confederate” question, this book explodes the old positions. No, there were no armies of willing African Americans fighting for the South. No, accounts of armed African American participation in the Confederate war effort are not the invention of 21st century neo-Confederates. Brasher presents evidence that some did take up arms during the Peninsula Campaign, if only under duress. Far more important, he conclusively shows that many northerners believed in 1862 that there were black Confederate soldiers as well as laborers, and those beliefs pushed the federal government toward emancipation. Brasher wisely leaves it for the reader to recognize the irony that the accounts of black Confederates cited today by those who imagine that the war was not about slavery and emancipation were in many cases written by abolitionists like Frederick Douglass to advance just the opposite point. No student of the Civil War who wants to give an informed answer when next confronted with the “black Confederate” question can afford to miss this fine book.

Gerald J. Prokopowicz is a Professor of History and Chair of the History at the University of East Carolina.