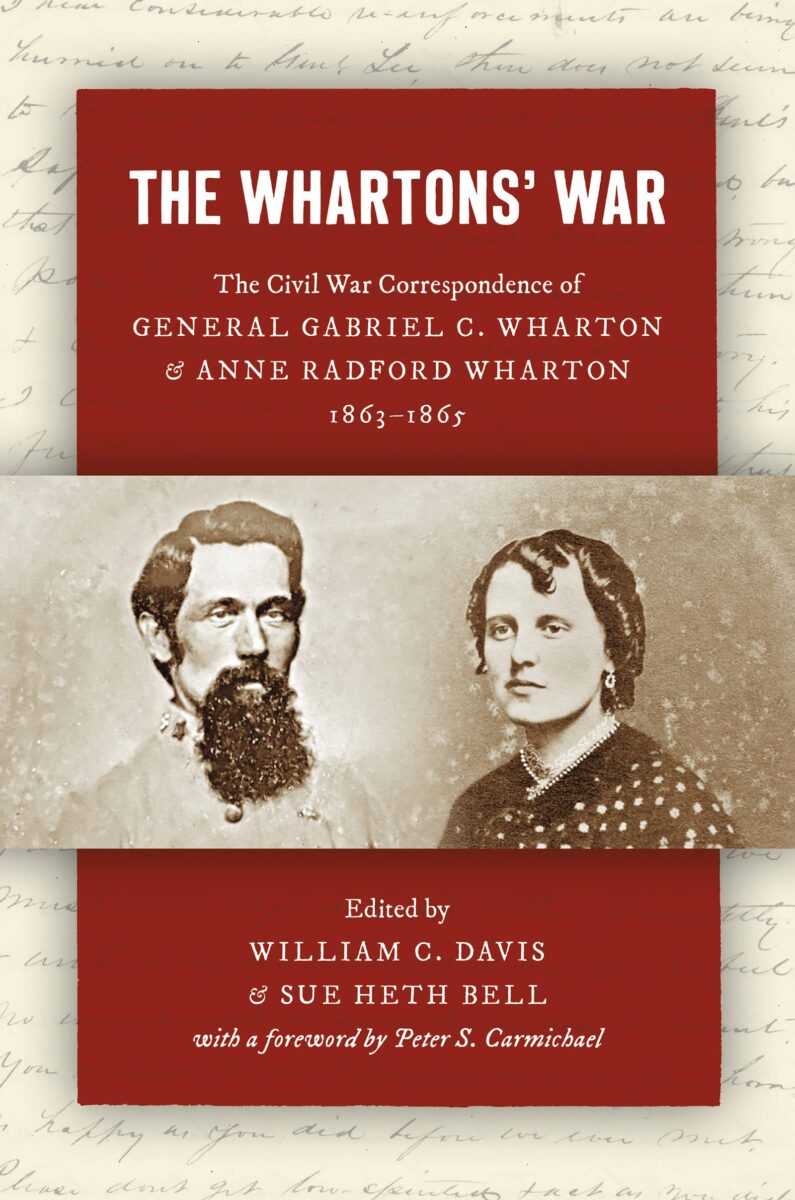

“Emotion” is a key word for reading the Civil War letters of Confederate General Gabriel C. Wharton and his wife Anne Radford Wharton. In recent years, historians such as Michael Woods and Peter Carmichael have focused attention on the need to study the role of human emotion in the Civil War era, and the Wharton correspondence offers many opportunities for doing just that. Here is a voluminous collection covering over three years of the war with no significant gaps.

In this valuable work, the war unfolds along with the Whartons’ evolving, complex, and often fraught relationship. Gabe was a VMI graduate and civil engineer; Nannie was nearly twenty years younger and the daughter of a substantial slaveholder. She was clearly impressed by him, and her early letters carry a decidedly deferential tone. Like many a wartime courtship, theirs had its up and downs, especially since her father’s permission to marry was by no means guaranteed.

During the war, both Gabe and Nannie were ardent Confederates, though their emotional lives often became entangled with their assessments of the southern nation’s prospects. The letters contain much detail on plans (often unsuccessful) to be with each other while Gabe is serving in the army. Gabe was ambitious for promotion and advancement, and Nannie was equally so. The pull of family commitments versus patriotic duty felt by so many Americans during the war years appeared in one way or another in many of the letters. Both Whartons struggled with ideas of honor in assessing their behavior as well as that of others.

The emotional content of the correspondence grew more intense when Nannie became pregnant. She had a somewhat difficult pregnancy, but also was emotionally fragile and prone to outbursts of temper or despair. Gabe’s letters sought to calm his wife, he too become quite frustrated both by their separation and the ups and downs of his military service.

During the period covered by the correspondence, Gabe served in Southwest Virginia, accompanied James Longstreet’s corps to East Tennessee, and distinguished himself during the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. For much of the war, Nannie remained at her family home, “Arnheim,” in the New River Valley of Southwest Virginia, where she closely followed the war news and worried about Yankee raids. An enslaved man and woman—Tim and Emeline—loom large in the correspondence, and even though they do not speak for themselves, the Whartons’ comments are often revealing about the changes occurring for both races. The war, separation, and slavery are all interwoven into the letters as Gabe and Nannie deal with problems in their marriage, the vicissitudes of military campaigns, and the humdrum but important details of life in camp and home. Gabe reported on his dreams, including one in which he committed adultery, and Nannie chronicled her many mood swings. Indeed, Nannie’s mercurial temperament and difficulties as both a wife and mother run through the entire correspondence.

Those interested in Confederate military history may wish Gabe had written about his service in more detail, but his letters well described problems in Confederate command, including great uncertainties about his own role. He offered much commentary on Confederate generals, repeated complaints about superior officers, and showed much concern for his soldiers’ welfare. Readers interested in Jubal Early will find frequent remarks from both Whartons, at first admiring but later sharply critical. Like most Confederates, Gabe greatly admired Robert E. Lee. He has little good to say about Jefferson Davis, and at one point said he had nearly lost faith in “republican government” altogether (80). Many of Gabe’s attitudes were undoubtedly shaped and sometimes soured by his longing to be home, especially as Nannie struggled through pregnancy and childbirth; indeed, the health of both mother and son remained unsettled for the duration of the war. Gabe’s letters from East Tennessee recaptured the problems of idleness, bad weather, food shortages, and other problems during a winter encampment.

The volume begins with a very useful preface and introduction that provides important context. In addition, the editors added extensive introductions to each of the twenty-seven chapters that help the reader navigate through the messy details of the Whartons’ wartime experiences. There is also a thorough and interesting account of their postwar lives. The volume needed a much stronger and more detailed subject index, but it would be wrong to end on a critical note. William C. Davis and Sue Heth Bell deserve much praise for presenting the Whartons’ story in such an effective way to what should be a most appreciative audience of readers and researchers.

George C. Rable is Professor Emeritus at the University of Alabama and the author of many books on the Civil War era, including the Lincoln Prize-winning Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!