Mary Boykin Chesnut

Two days after the fall of Fort Sumter, 38-year-old South Carolinian Mary Boykin Chesnut sat down with her journal—something she’d done faithfully since the beginning of the secession crisis and would continue to do throughout the entirety of the Civil War. She’d been in Charleston during the bombardment before returning to her home in Camden, South Carolina. What follows are her first two post-Sumter entries—a personal look at the beginning of the war through the eyes of an elite southern woman.

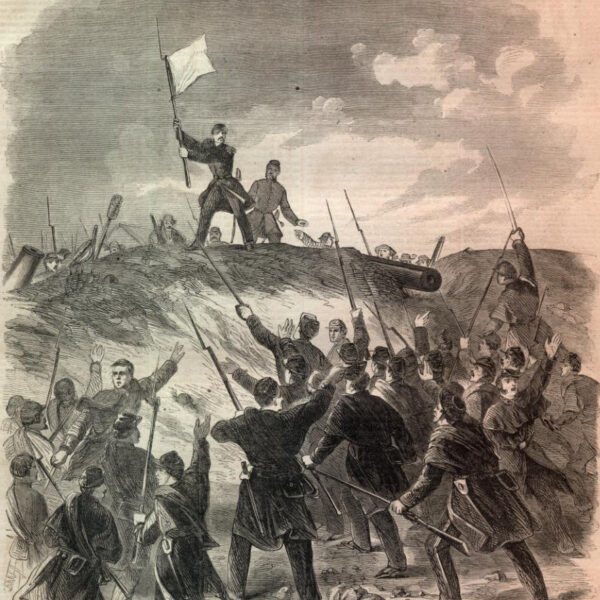

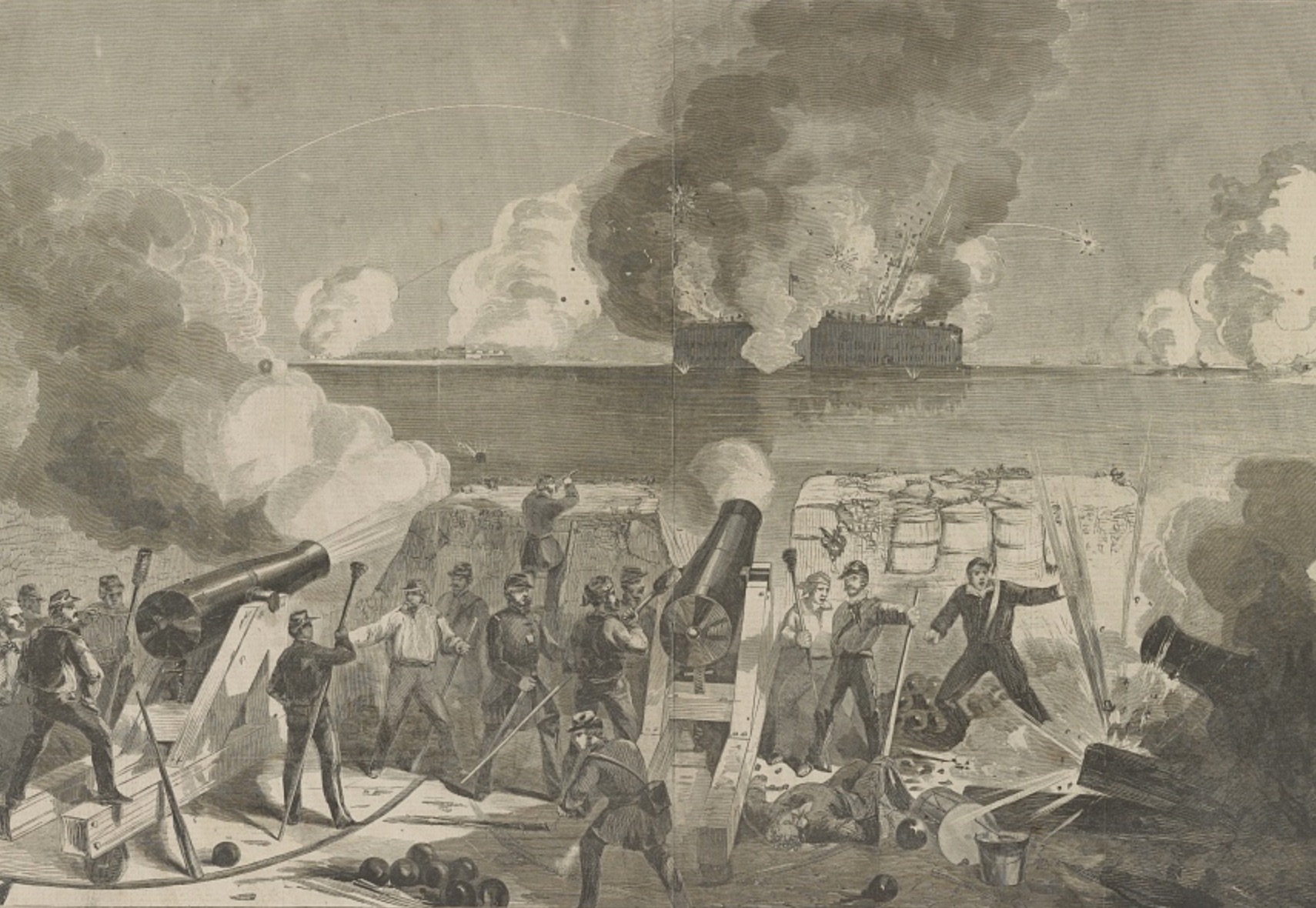

April 15th. I did not know that one could live such days of excitement. Some one called: “Come out! There is a crowd coming.” A mob it was, indeed, but it was headed by Colonels Chesnut and Manning. The crowd was shouting and showing these two as messengers of good news. They were escorted to Beauregard’s headquarters. Fort Sumter had surrendered! Those upon the housetops shouted to us “The fort is on fire.” That had been the story once or twice before. When we had calmed down, Colonel Chesnut, who had taken it all quietly enough, if anything more unruffled than usual in his serenity, told us how the surrender came about. Wigfall was with them on Morris Island when they saw the fire in the fort; he jumped in a little boat, and with his handkerchief as a white flag, rowed over. Wigfall went in through a porthole. When Colonel Chesnut arrived shortly after, and was received at the regular entrance, Colonel Anderson told him he had need to pick his way warily, for the place was all mined. As far as I can make out the fort surrendered to Wigfall. But it is all confusion. Our flag is flying there. Fire-engines have been sent for to put out the fire. Everybody tells you half of something and then rushes off to tell something else or to hear the last news. In the afternoon, Mrs. Preston, Mrs. Joe Heyward, and I drove around the Battery. We were in an open carriage. What a changed scene the very liveliest crowd I think I ever saw, everybody talking at once. All glasses were still turned on the grim old fort. Russell, the correspondent of the London Times, was there. They took him everywhere. One man got out Thackeray to converse with him on equal terms. Poor Russell was awfully bored, they say. He only wanted to see the fort and to get news suitable to make up into an interesting article. Thackeray had become stale over the water.

Charleston, South Carolina, during the Civil War

Mrs. Frank Hampton and I went to see the camp of the Richland troops. South Carolina College had volunteered to a boy. Professor Venable (the mathematical), intends to raise a company from among them for the war, a permanent company. This is a grand frolic no more for the students, at least. Even the staid and severe of aspect, Clingman, is here. He says Virginia and North Carolina are arming to come to our rescue, for now the North will swoop down on us. Of that we may be sure. We have burned our ships. We are obliged to go on now. He calls us a poor, little, hot-blooded, headlong, rash, and troublesome sister State. General McQueen is in a rage because we are to send troops to Virginia. Preston Hampton is in all the flush of his youth and beauty, six feet in stature; and after all only in his teens; he appeared in fine clothes and lemon-colored kid gloves to grace the scene. The camp in a fit of horse-play seized him and rubbed him in the mud. He fought manfully, but took it all naturally as a good joke. Mrs. Frank Hampton knows already what civil war means. Her brother was in the New York Seventh Regiment, so roughly received in Baltimore. Frank will be in the opposite camp. Good stories there may be and to spare for Russell, the man of the London Times, who has come over here to find out our weakness and our strength and to tell all the rest of the world about us. CAMDEN, S. C., April 20, 1861. Home again at Mulberry. In those last days of my stay in Charleston I did not find time to write a word. And so we took Fort Sumter, nous autres; we—Mrs. Frank Hampton, and others—in the passageway of the Mills House between the reception-room and the drawing-room, for there we held a sofa against all comers. All the agreeable people South seemed to have flocked to Charleston at the first gun. That was after we had found out that bombarding did not kill anybody. Before that, we wept and prayed and took our tea in groups in our rooms, away from the haunts of men.

The bombardment of Fort Sumter

Captain Ingraham and his kind also took Fort Sumter from the Battery with field-glasses and figures made with their sticks in the sand to show what ought to be done. Wigfall, Chesnut, Miles, Manning, took it rowing about the harbor in small boats from fort to fort under the enemy’s guns, with bombs bursting in air. And then the boys and men who worked those guns so faithfully at the forts they took it, too, in their own way. Old Colonel Beaufort Watts told me this story and many more of the jeunesse doree under fire. They took the fire easily, as they do most things. They had cotton bag bomb-proofs at Fort Moultrie, and when Anderson’s shot knocked them about some one called out “Cotton is falling.” Then down went the kitchen chimney, loaves of bread flew out, and they cheered gaily, shouting, “Bread-stuffs are rising.” Willie Preston fired the shot which broke Anderson’s flag-staff. Mrs. Hampton from Columbia telegraphed him, “Well done, Willie!” She is his grandmother, the wife, or widow, of General Hampton, of the Revolution, and the mildest, sweetest, gentlest of old ladies. This shows how the war spirit is waking us all up. Colonel Miles (who won his spurs in a boat, so William Gilmore Simms said) gave us this characteristic anecdote. They met a negro out in the bay rowing toward the city with some plantation supplies, etc. “Are you not afraid of Colonel Anderson’s cannon?” he was asked. “No, sar, Mars Anderson ain’t daresn’t hit me; he know Marster wouldn’t ‘low it.” I have been sitting idly to-day looking out upon this beautiful lawn, wondering if this can be the same world I was in a few days ago. After the smoke and the din of the battle, a calm.

Source

A Diary From Dixie (1906), 39–43.