Confederate first lady Varina Davis, the subject of a new novel by Charles Frazier, as she appeared shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War

A young woman in an unhappy marriage whose rise to first lady makes her both exhilarated and uncomfortable. Her much older husband, loyal only to himself and the power that the presidency will bring him. A past so riddled with lies they tell themselves that nothing is certain.

Charles Frazier’s new Civil War novel, Varina, feels strangely relevant in 2018.

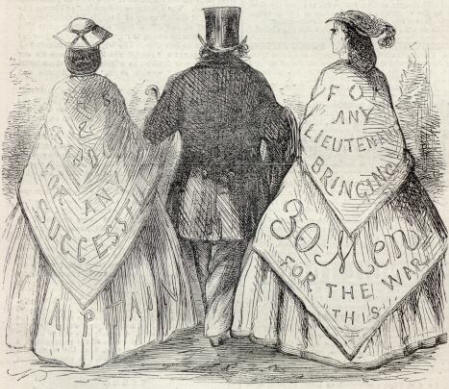

The novel’s protagonist is “V,” better known as the Confederacy’s only first lady, Varina Howell Davis, who married Jefferson Davis when she was 18 years old and he was 36. She chafed against gender convention, often speaking her mind and reveling in her prewar role as an engaging and witty dinner party hostess in Washington. Her actions during and after the Civil War, however, were controversial, provoking rumors that she was not devoted enough to the nation her husband helped to create. Varina supported the South in public but also visited Union prisoners in Richmond hospitals and maintained correspondence with friends in the North. After Jefferson Davis died in 1889, she moved to New York City and wrote pieces for northern papers that advocated for sectional reunion.

Although she was never ardently proslavery, Varina was fully aware that she had benefited from the slave system—and did nothing to resist it. After the war, when her former house slave Ellen tells reporters that her owner was “nice enough,” Varina simultaneously understands and resents that assessment: “V kept thinking, Just all right? Nice enough? We were friends.” In the end, as Frazier shows, Varina is the kind of fictional antihero who has become popular of late: a flawed person whose understandings of herself and the world around her are often compromised. If he were an academic, Frazier would be a dark historian; what he finds so interesting in Varina is her simultaneous hatred of and complicity in the ideologies and actions of the Confederacy.

Frazier is also interested in getting the history right. His acknowledgements include a bibliography that lists Joan Cashin’s biography of Varina, First Lady of the Confederacy (2006), and William Cooper’s examination of her husband, Jefferson Davis, American (2001), among other texts. Frazier’s depiction of the Confederacy’s collapse and the Davis family’s resulting escape from Richmond in the spring of 1865 is deeply rooted in historical detail. Of course, as a novelist and not a historian, Frazier can create visceral images that transport you to the time and place. In Montgomery, at the beginning of the war, red clay oozes between cobblestones, “like margins of recent wounds still weeping.”

Author Charles Frazier

As he proved in his breakout Civil War novel, Cold Mountain, Frazier is adept at conveying the terror of a journey into an unknown landscape. Varina’s flight from Richmond is the best sequence of the book. Although we know what happened, Frazier still generates almost unbearable tension as Varina, her children, Ellen, and a band of armed protectors make their slow, ominous passage through the swamps and forests of the deep South.

But history also constrains Frazier. Cold Mountain’s Inman, Ada, and Ruby were embedded in history, but they were fictional characters that the reader, not knowing how the story would end, could become invested in. Varina’s life is well-known, and she is not so easy to like. The pleasure of this novel is in Frazier’s beautiful writing and the non-chronological narrative structure.

Varina’s story is, as the character herself describes, “distracted by memory—its habit of looping and echoing.” The action jumps from 1906 Saratoga Springs, where Varina is trying to break an opiate addiction, to the end of the war, to her days as a teenage bride, and back again. The impetus for her memories is James Blake, an African-American schoolteacher who has realized late in life that he spent part of his childhood with the Davises. He remembers little and wants the former first lady to fill in the blanks—how she “adopted” him, known then as Jimmie Limber, off the street to live with her at the Confederate White House and why he joined them as a fugitive from the Yankees. She obliges, and the novel takes the form of her memories, with all of their looping and echoing.

The importance of war memory—and its unreliability—is unsettling to contemplate in 2018, as the events of Charleston and Charlottesville continue to reverberate. In an interview with NPR, Frazier gestured to this, and to the other ways that his new novel feels modern. “After Cold Mountain,” he said, “I never thought I wanted to write about the Civil War again. But as the past three or four years have shown, it’s not done with us—as a country, as a culture.”

As Varina says in one of her final conversations with Blake, “Remembering doesn’t change anything—it will always have happened. But forgetting won’t erase it either.” In a way, Varina is a perfect Confederate monument for our time: It reveals all of the racism and the greed and the violence of the Confederate worldview, and the flawed and broken humanity of those who fought for it.

Megan Kate Nelson is a writer living in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Her book manuscript about the Civil War in the desert Southwest, which won a 2017 NEH Public Scholar Award, will be published by Scribner in 2020.

This article appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of The Civil War Monitor.