Nurse Annie Bell tends to wounded soldiers after the Battle of Nashville. Many injured troops, North and South, would become addicted to opiates.

Hidden among the many headlines about the United States’ ongoing opioid crisis was an important press release issued by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) earlier this summer. On Thursday, June 8, the FDA requested that drug manufacturer Endo Pharmaceuticals pull the opioid Opana ER from the market. Opana is notorious for its extraordinary power and addictiveness—even compared to other synthetic opioids—and for its causative role in Indiana’s 2015 HIV outbreak. The FDA asked for Opana to be pulled from pharmacy shelves on the grounds that the “benefits of the drug may no longer outweigh its risks,” meaning that the likelihood that patients might become addicted to Opana was greater than the pain relief the drug might bring them.[1]

Although the FDA’s action toward Opana was an extraordinary, welcome step in the unbridled public health crisis that is today’s opioid addiction epidemic, public health experts warn that it will make little difference toward ending the problem. Drug markets where Opana is common are flooded with many other opioids, ranging from synthetic prescription drugs to opium-derived heroin.[2] Take West Virginia, for example, which has one of the highest opioid prescription rates in the nation. Between 2010 and 2016 drug retailers sent about 780 million hydrocodone and oxycodone pills into the state, which has only 1.8 million residents—that’s 433 opioid pills per person.[3] This eye-opening figure illustrates why the FDA’s attempt to reduce the supply of opioids by banning Opana are akin to plugging the U.S. drug policy’s iceberg-sized gash with a single, tiny cork.

Still, as the FDA pointed out, the significance of its decision to pull Opana from pharmacies lies in its symbolism, not its effect. Rather than a cure-all, the FDA’s ban of Opana is instead a bellwether that represents a change in the public health community’s strategy toward addressing opioid addiction. As it turns out, attempting to decrease levels of addition by reducing the supply of opioids is not a new strategy. In fact, Civil War-era doctors developed a similar plan to combat their own contemporary opiate addiction epidemic.[4]

Several historians note that although the number of Americans suffering from drug addiction is higher than ever before, today’s opioid epidemic is not strictly unprecedented.[5] Nineteenth-century Americans were all too familiar with addiction to opiates, made so through the experiences of antebellum women and men, and later, Civil War veterans.[6] The parallels between the two addiction epidemics are striking. Like today’s crisis, conceived out of the irresponsible prescribing of opioids by doctors during the 1990s and 2000s, the Civil War era also saw an opiate addiction crisis derived in part from the widespread medicinal use of painkillers.[7]

“The one indispensable drug on the battlefield”

Opiates were the first line of defense in army doctors’ war on pain and camp illnesses during the Civil War. The Union army alone requisitioned 10 million opium pills, not including the various other opium-based compounds, tinctures, derivatives (like the alkaloid morphine), or patent medicines marketed by sutlers to soldiers that sometimes contained opiates.[8] Every day on battlefields and in hospitals, northern and southern surgeons dispensed opium, laudanum, and morphine to soldiers ailing from a variety of conditions.

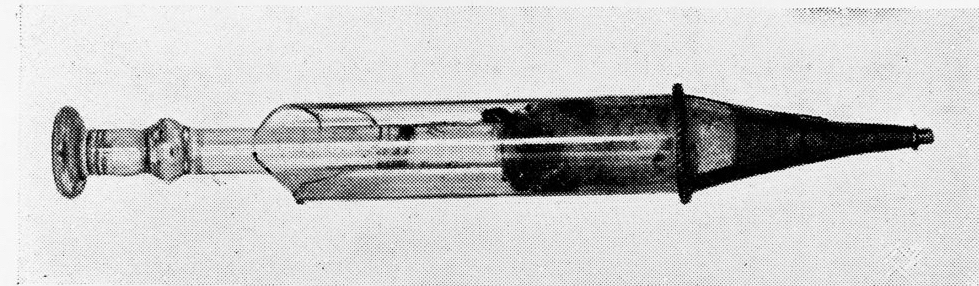

This hypodermic syringe, created by Dr. Alexaner Wood in the 1850s, saw wide use during the Civil War.

Powdered opium and liquid morphine were often given to soldiers suffering from gunshot wounds. One Union physician, William W. Keen, reported that upon finding injured soldiers, he treated their pain by using the tip of a knife as a measure, filling it with powered opium, and dusting it over the men’s open wounds.[9] Morphine, which was about 10 times more powerful than opium, became the narcotic of choice for many doctors and patients during and after the Civil War because, as some historians argue, the Union army issued hypodermic syringes to its medical corps, bringing the device into the mainstream of American medicine for the first time.[10]

Opiates were also useful remedies for the intestinal sicknesses that were soldiers’ constant companions. As Union surgeon general William A. Hammond famously quipped, Civil War soldiers were wounded and fell ill during “the medical middle ages,” before the germ theory of disease allowed medicine to explain the cause of illnesses like infection and to effectively prevent them. So in most cases, physicians could do little for patients other than treat symptoms. To this end, opium and its derivatives caused constipation, which doctors believed was healthier than the alternative—potentially fatal dehydration brought on by dysentery and diarrhea.[11] In appreciation of its many uses, the Confederate military manual concluded in 1863 that opium was a must-have for physicians. “Opium,” it instructed Confederate medical personnel, “is the one indispensable drug on the battlefield—important to the surgeon, as gunpowder to the ordnance.”[12]

Pain and sickness did not necessarily dissipate after the war’s end. Many veterans suffered from the lingering effects of their wartime service for years, necessitating the continued use of opiates. In 1867, Union physician S. Weir Mitchell reported administering 20 to 30 injections of morphine daily to veterans still hospitalized for their war injuries at Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia.[13]

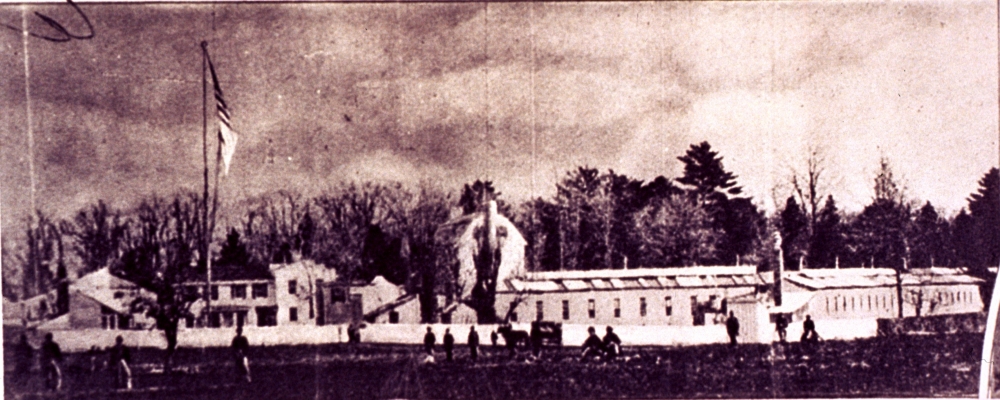

Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia

Because opiates were so effective at mitigating pain, were unregulated, and could be bought on demand—and of course were addictive—many former soldiers continued their opiate regimens throughout their postwar lives. Physicians from the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the precursor to today’s Veterans Affairs hospital system, treated nearly 1,200 cases of morphine addiction among veterans who retired to the system’s old soldiers’ homes between 1885 and 1900.[14] Civilians eventually noted the close connection between veterans and opiates, surmising that many men became addicted through opiate-wielding military doctors.[15] Observers even dubbed morphine addiction “the army disease.”[16]

Then and Now

Yet the somber parallels between America’s opiate and opioid crises do not stop at their similar origin stories. Like a broken record, today’s response of the American medical community to opioid addiction unknowingly parrots the response of Civil War-era physicians to veterans’ opiate addiction during the late 19th century.

Well into the postwar decades, physicians feared that maimed and traumatized Civil War veterans were heavily abusing opium and morphine. In 1871, the pioneering medical researcher and former Union army physician Jacob Mendes da Costa explained how doctors might cause addiction by over-relying on opiates to treat veterans’ ailments. He warned physicians not to employ opium as a long-term

A morphine bottle produced during the Civil War

remedy for chronic illnesses, because as he put it, “in the long continuance of the treatment required there would have been great risk of making the patient an opium eater.”[17] Another physician even anticipated the FDA’s reasoning and language regarding its Opana decision. He wrote: “Opium … is also liable to great abuse, and if we estimate its uses and abuses, it is quite possible that the injuries of the one would quite outdo the benefits of the other.”[18]

During the 1870s and 1880s, medical journals bear witness to doctors’ robust debate about how best to resolve the opiate addiction epidemic. Some physicians proposed a measure resembling the FDA’s recent action toward Opana—they called for the removal of morphine from apothecary shops. The editors of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal took this impulse the farthest in an 1889 report on morphine addiction. “[I]f, finally, apothecaries could be brought to exercise proper care and vigilance in dispensing morphine, never giving it except under a physician’s order, the evil would be virtually suppressed,” they reasoned.[19] Because the practice of medicine and dispensing of drugs were virtually unregulated until the early 20th century, this call to restrict the availability of morphine was an extreme measure in its day.

Ultimately, few organized steps were taken to restrict the availability of opium and morphine in the U.S. until the early 1900s.[20] Yet ironically, like today, reducing the availability of opiates by restricting apothecaries’ ability to dispense them would have had little effect upon Civil War-era America’s addiction epidemic, because the drug market was saturated with unregulated patent medicines compounded from opiates. With the experience of Civil War veterans and physicians in mind, it seems with each passing headline that the Civil War-era opiate addiction crisis and the opioid epidemic of today have too much in common for comfort.

Jonathan S. Jones is a history Ph.D. candidate at Binghamton University. He researches opiate addiction in the U.S., especially its origins in the 19th century. His dissertation, “A Mind Prostrate: Physicians, Opiates, and Insanity in the Civil War’s Aftermath,” is a study of the Civil War-era opiate addiction epidemic, tracing how physicians responded to opiate “insanity” among war survivors by attempting to radically reform American medicine. You can reach him by email at [email protected].