Author Shelby Foote

Asked to name the writer whose work had the greatest influence on their early love for the Civil War, most lay students of the conflict would offer one of two responses: Bruce Catton or Shelby Foote. Each wrote as if they owned the Civil War, and for millions of readers they brought America’s greatest conflict to life in a way that few historians, however gifted, had done. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, Catton, a journalist, wrote more than a dozen books on the conflict, most notably his Army of the Potomac trilogy; his three-volume Centennial History of the Civil War; two volumes covering the wartime career of General Ulysses S. Grant; and The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War, the gateway drug to a generation of Civil War buffs. Foote, a novelist, wrote during the same period, although his fame rests upon the single massive work, The Civil War: A Narrative. Between them, these nonprofessional historians and near contemporaries have a strong claim to being the greatest bards of the American Iliad.

Catton (1899–1978) published his first book of Civil War history in 1951, Foote (1916–2005) in 1958 (six years after his historical novel Shiloh). On completing his mammoth Civil War trilogy in 1975, Foote would return to writing fiction. Catton was the better known in his own time—until in the 1990s, when Foote became at least as famous, thanks to extensive screen time as a “talking head” in Ken Burns’ 1990 PBS documentary, The Civil War.

Speaking for myself, it was Catton, not Foote, who drew me to the Civil War (and who, more than that, made me want to write history). From the time I was 12 and discovered A Stillness at Appomattox, the Pulitzer Prize-winning final volume of his Army of the Potomac trilogy, I read everything by Catton I could lay my hands on. I don’t think I had even heard of Foote until 1979, when I chanced upon The Civil War: A Narrative on a dusty shelf in my college library. I mentioned the find to one of my professors, who airily dismissed Foote as “a poor man’s Bruce Catton,” thereby extinguishing any curiosity I had about Foote.

As it turned out, that was very much my loss. So let me make amends for that youthful slight by turning first to Foote in this appreciation of the bards of the Civil War.

In 1954 the president of Random House, Bennett Cerf, approached Foote about writing a short history of the Civil War. Foote was 37, an up-and-coming novelist from Mississippi Delta country who had come to Cerf ’s notice with his 1952 novel, Shiloh. By a “short” history, Cerf meant something in the range of 200,000 words. That seemed easy enough; Foote estimated that he already wrote 100,000 words a year as a novelist and figured he could double that output as a historian. “Fiction is hard work,” he later said; “history, I figured, well, there’s not much to that.”[1] He decided he could execute the entire project in 18 months (one year for the rough draft plus six months to revise it).

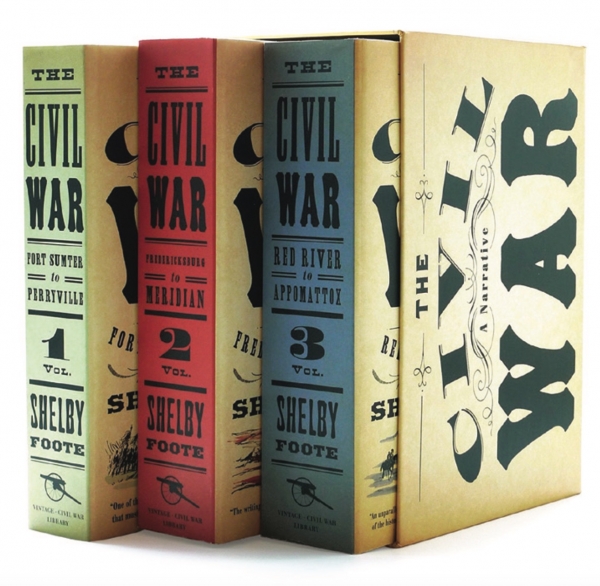

Instead he spent 20 years—and ended up producing not a short history of the war but a sprawling trilogy totaling 2,968 pages and, by Foote’s estimate, 1,655,000 words. He liked to joke that it took him five times longer to write the Civil War than it took the soldiers to fight it, but that in his defense, “there were a good many more of them than there was of me.”[2]

The length was intentional. As soon as the ink was dry on the contract with Random House, Foote made a detailed outline of the project, concluding that to cover the war without just skittering along the surface, he would need well over 200,000 words. He wrote the press: “Instead of a short history, I think I would rather do this three-volume thing, running about 500,000 or 600,000 words a volume.”[3] Random House approved the change, issued a new contract, and Foote set to work. Neither he nor the publisher realized it would require two decades. “If I had had any idea that it was going to take twenty years out of the middle … of my writing life,” Foote told an interviewer in 1978, “I would not have started the War.”[4]

Foote worked with several principles in mind, among them: He would give equal coverage to the western and eastern theaters (this at a time when Civil War military historians still focused mainly on Virginia); he would operate according to the Aristotelian dictum that stories should have a beginning, middle, and end (each volume follows that trajectory); he would keep the political history to a minimum and ignore the war’s social, cultural, and economic history altogether; he would eschew footnotes, on the theory that they would pull the reader out of the dramatic world he intended to create; and he would bring his skill as a novelist fully to bear. “Dramatize! Dramatize!” he told himself. “But don’t goose it up.”[5]

Foote immersed himself in the war, visiting the major battlefields (and many minor ones) and even growing a beard for the first time in his life, because most Civil War soldiers had beards. Along the way he sent regular reports to his close friend and fellow novelist, Walker Percy. “Work goes slow and well,” ran a typical letter, “particularly on little-known events, like Roanoke Island, whose neglect I cannot understand, now that I know how important they were. Loss of the island, for instance, lost the Confederacy the whole NC coast…. Also it began the career of [Major General] Ambrose Burnside—so perhaps it was a Southern gain after all, collectable at Fredericksburg.”[6]

Volume 1, Fort Sumter to Perryville, came out in 1958; volume 2, Fredericksburg to Meridian, appeared in 1963. For a variety of reasons, most having nothing to do with the project, volume 3, Red River to Appomattox, did not appear for another 12 years, in 1975. Reviews of each volume were similar, with critics—mainly academic historians—acknowledging the vividness of Foote’s prose but complaining that his work focused almost entirely on battles and lacked the proper citation apparatus (while conceding it was obvious that Foote had consulted hundreds of sources and employed no dramatic license). This occasionally resulted in unfavorable comparisons to Catton, whose books had equivalent literary flare but were far more wide-ranging and did provide citations.

Foote was unrepentant, and had his own opinions of academic historians. Generally speaking, he maintained, they lulled readers to sleep with analytical accounts of events: “It’s what makes historians such poor reading, and I’m not talking about being entertaining, I’m talking about what makes you dissatisfied with a historian…. A lot of modern historians are scared to death to suggest that life has a plot. They’ve got to take it apart and have a chapter on slavery, a chapter on ‘The Armies Meet,’ chapters like this, that, and the other.”[7]

In the end, Foote received a strong defense from C. Vann Woodward, an academic historian and the undisputed dean of southern history. In a review of the final volume of The Civil War: A Narrative, Woodward warned, “Professionals do well to apply the term ‘amateur’ with caution to the historian outside their ranks. The word does have deprecatory and patronizing connotations that occasionally backfire. This is especially true of narrative history, which nonprofessionals have all but taken over. The gradual withering of the narrative impulse in favor of the analytical urge among professional academic historians has resulted in a virtual abdication of the oldest and most honored role of the historian, that of storyteller. Having abdicated … the professional is in a poor position to patronize amateurs who fulfill the needed function he has abandoned.”[8]

And after a survey of Foote’s book’s chief characteristics, Woodward went after academic historians again: “But what has all this to teach our ‘psycho-historians,’ our ‘cliometricians,’ and our crypto-analysts busy with their neat models, parameters, and hypotheses?” he asked. “It is hard to say for sure. It is possible, however, that the 1,100 pages of this raw narrative, bereft as it is of ‘insight,’ might serve to expose them to the terrifying chaos and mystery of their intractable subject and disabuse them of some of their illusions of mastery.”[9]

MARK GRIMSLEY, A HISTORY PROFESSOR AT THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY, IS THE AUTHOR OF SEVERAL BOOKS, INCLUDING AND KEEP MOVING ON: THE VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN, MAY–JUNE 1864 (2002) AND THE HARD HAND OF WAR: UNION MILITARY POLICY TOWARD SOUTHERN CIVILIANS, 1861– 1865 (1995). HE HAS ALSO WRITTEN MORE THAN 50 ARTICLES AND ESSAYS.

This article appeared in the Spring 2020 (Vol. 10, No. 1) issue of The Civil War Monitor.