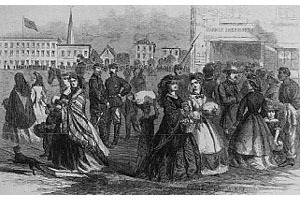

In a New Orleans cemetery in 1863, a woman and her daughters adorn the graves of loved ones killed during the war.

For decades, books about the Confederate homefront were often books about elite white slave-owning women—first Lost Cause-era flowery homages to their patriotism and dedication to the Confederacy, then more critical analyses drawing on the reams of letters and diaries they left behind. The homefront was often constructed as a bounded space, generally far away from the battlefield, virtually untouched by the messiness of combat. The war might intrude, in the form of letters or visits from furloughed kin, or sometimes “Yankee” interlopers disrupting the world of women. Of course, the Confederate homefront was never so simple, and the late-20th-century social history revolution brought new insights to the field. In general, works about the homefront written since the 1970s have fallen into two categories: community studies (which could encompass either a single city or county, a group of counties, or even an entire state) and more thematic or overarching approaches.

As historians became increasingly interested in questions of nationalism, class conflict, and loyalty within the Confederacy, the homefront took on new prominence, as those historians explored the impact of ordinary citizens on the outcome of the war. Historians recognized that even when the Confederacy was winning victories on the battlefield, it was losing ground at home, as the institution of slavery crumbled and food supplies dwindled. African Americans played a crucial role in this struggle as they resisted and ran to Union lines. Given the geographic size of the Confederacy, it’s impossible to think of the homefront as a single space; rather there were multiple fronts, one for every household. This list is by its very nature idiosyncratic, but I think taken together these five books give a sense of the breadth and richness of this topic.

THE DIARY OF DOLLY LUNT BURGE, 1848–1879

(University of Georgia Press, 1997)

Edited by Christine Jacobsen Carter

Dolly Lunt Burge was an affluent young widow in Georgia when she began her diary in 1848, far from her family and native Maine. By the time she wrote her last entry in 1879, she had been married and widowed twice more, raised a family, ran a large plantation, and managed its transition to free labor. She is less well known than other Confederate diarists like Mary Chesnut or Sarah Morgan, but no less eloquent. The long span of her entries gives the reader the texture and rhythm of daily life, showing the degree to which her home was relatively untouched by the war until 1864. Burge’s diary comes alive when she describes William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea enveloping her property, and then in the years after as she coped—often angrily—with the upending of her world that came with emancipation. Although her entries taper off considerably during Reconstruction, their inclusion in this published version remind us that the war at home did not end when the battles did.

UNRULY WOMEN: THE POLITICS OF SOCIAL AND SEXUAL CONTROL IN THE OLD SOUTH

UNRULY WOMEN: THE POLITICS OF SOCIAL AND SEXUAL CONTROL IN THE OLD SOUTH

(University of North Carolina Press, 1992)

By Victoria E. Bynum

Victoria Bynum’s study of “unruly” women in the North Carolina Piedmont revolutionized the study of the Civil War homefront. What made her subjects unruly was their unwillingness to be contained by the power of the state in the antebellum and war years: complaining publicly about abuse by men, engaging in forbidden sexual behaviors, and finally defying or challenging the Confederacy. Bynum’s subjects are not elites like Dolly Burge; rather they are non-slaveholding whites, free blacks, and enslaved women. Their common struggles to survive during wartime led them to turn to petty theft, prostitution, illegal trade, and at times open protest (as during bread riots). Bynum mines court records and a variety of other public documents to excavate the lives of women (and their families) who were left out of Lost Cause tales of dedicated women and faithful slaves. The class conflict and dissent that she uncovers complicates the picture of a largely unified Confederacy with only isolated pockets of unionism. Rather, it was a place full of internal conflict, and those conflicts often grew out of family concerns rather than the lofty rhetoric of liberty and secession. But as Bynum shows, the personal could quickly become the political.

OUT OF THE HOUSE OF BONDAGE: THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE PLANTATION HOUSEHOLD

(Cambridge University Press, 2008)

By Thavolia Glymph

Thavolia Glymph’s brilliant and searing book turns the home—or household—into a literal battlefield. Her work reminds readers that the mythical plantation household was never peaceful and free of violence, and was always a site of work and struggle. She systematically dismantles the myth that there was any kind of sisterhood or affinity between mistresses and the women who labored for them. Rather, enslaved women resisted when they could, pushing back against their female owners, who in turn responded physically. Enslaved women seized on wartime upheaval to further disrupt the institution of slavery and emancipate themselves. Glymph’s work takes Dolly Lunt Burge’s postwar complaints about the challenges of free labor and turns them around, showing how freedwomen sought to control their own labor in ways that had previously been impossible. Freedwomen, traditionally seen as relatively powerless, are shown articulating their rights as both workers and citizens. This beautifully written book forces us to reconsider the myths that often shrouded elite white women in a mantle of gentility and manners, reminding us of the brutality at the heart of the Civil War-era South.

ROUTES OF WAR: THE WORLD OF MOVEMENT IN THE CONFEDERATE SOUTH

ROUTES OF WAR: THE WORLD OF MOVEMENT IN THE CONFEDERATE SOUTH

(Harvard University Press, 2012)

By Yael A. Sternhell

When we think of the homefront, we think of a static place: a farm, a neighborhood, a city. In the powerfully original Routes of War, Yael Sternhell puts the Confederacy in motion. Its roads were constantly flooded with people—soldiers moving around the landscape from camp to battlefield, but also stragglers and deserters, and thousands upon thousands of refugees, both white and black. This vast swirl of humanity was rarely organized, and created a powerful sense of disorder among civilians, many of whom came to believe that the Confederate state could not protect them from internal as well as external enemies. White southerners who thought they were safely behind the lines saw their fields raided and trampled by their own soldiers as they marched to the front; later in the war, deserters on the move literally embodied the Confederacy’s collapse. By far the most disturbing change to white southerners came with the presence of African-American refugees, who ran to Union lines or otherwise sought their freedom. The roads, rather than binding the Confederacy together, seemed to be the fraying threads of its disintegration.

EMBATTLED FREEDOM: JOURNEYS THROUGH THE CIVIL WAR’S SLAVE REFUGEE CAMPS

(University of North Carolina Press, 2018)

By Amy Murrell Taylor

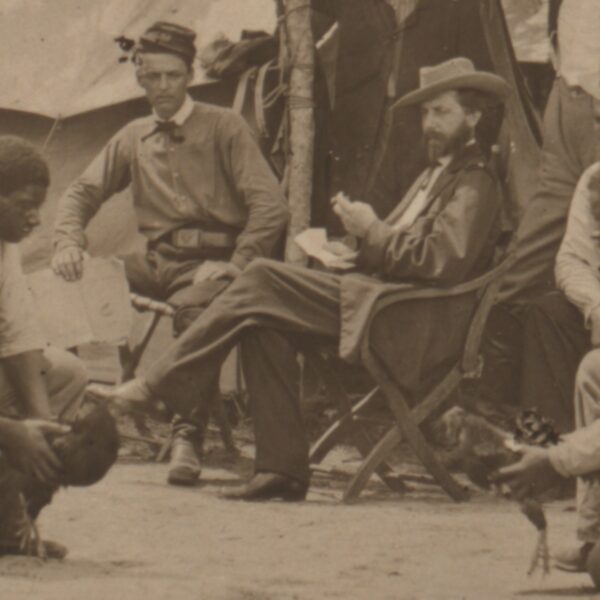

The 500,000 African Americans who fled to the Union lines and became known as “contrabands” (or in Taylor’s preferred phrase, “slave refugees”) forged new lives in the worst of circumstances. Their lives in Union refugee camps, as Taylor shows in her powerful and eloquent book, were a kind of semi-freedom, no longer bound to masters, but instead under the tight controls of the federal government. With meticulous research and deep sensitivity, Taylor reconstructs the lives of black men and women who struggled to survive against disease, mistreatment at the hands of Union soldiers, and repeated forced relocations. Some of the best chapters of this multiple prize-winning work look at the material conditions of refugee lives: the rations they received, the clothing and housing they did (and did not) get, the labor they were forced to provide. The refugee camps were a different kind of homefront, where the enemy was not opposing troops, but the elements and indifference.

ANNE SARAH RUBIN IS A PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY. SHE IS THE AUTHOR OF A SHATTERED NATION: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE CONFEDERACY(2005) AND THROUGH THE HEART OF DIXIE: SHERMAN’S MARCH AND AMERICAN MEMORY(2014) AND THE CO-EDITOR OF THE PERFECT SCOUT: A SOLDIER’S MEMOIR OF THE GREAT MARCH TO THE SEA AND THE CAMPAIGN OF THE CAROLINAS(2018).

This article appeared in the Fall 2020 (Vol. 10, No. 3) issue of The Civil War Monitor.