Founded in 1818, Brooks Brothers of New York is the oldest clothing retailer in America. Even today, the name alone conjures images of fine silk neckties and Italian wool sportscoats—quality, luxurious, expensive products. Touting a patriotic commitment to American presidents and the armed forces, a pamphlet published to mark the company’s 100th anniversary declared: “During and after the Civil War, it had many distinguished officers … as patrons, among whom were Generals Grant, Sheridan, Hooker, and Sherman. It is also said that the coat worn by Lincoln on the night of his assassination was made by Brooks Brothers.”[1] It was a splendid coat; crafted for Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, the black wool greatcoat featured silk lining with an intricately embroidered eagle and the inscription, “One Country, One Destiny.”[2]

Not all Brooks Brothers menswear was of such quality. Union soldiers in 1861 received lesser goods—or shoddy uniforms—from Brooks Brothers and other manufacturers.[3] “‘Shoddy,’ properly speaking,” explained one 19th-century writer, “is the short wool carded or worn from the inside of cloth, without fibre or tenacity, and with no capability of wear, and yet easily made into the semblance of more durable goods. The same is now used, however, as applied to cloth, in a more general sense—to signify any description of rotten or improper material.”[4]

Outfitting a volunteer army was a monumental task. Mistakes were made—some honest, some dishonest. And during the war’s first months, many soldiers went into the field with subpar equipment and in uniforms made from shoddy wool. With their trousers disintegrating, some “wearers were exposing too much of their anatomy.”[5]

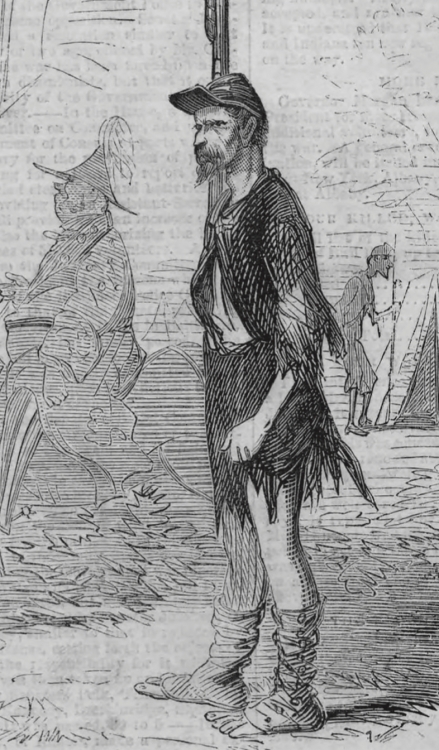

This cartoon, published in Harper’s Weekly in August 1861, depicts a Union soldier who received a shoddy, or poor quality, uniform upon enlistment—the “victim” of contractors “who have ‘influence’ at Washington,” as its caption notes.

The Civil War, however, expanded the definition of shoddy. By late 1861, all badly made goods were shoddy—“shoddy coats, shoddy shoes, shoddy blankets, shoddy tents, shoddy horses, shoddy arms, shoddy ammunition, shoddy boats, shoddy beef and bread.”[6] While associated with northeastern war contractors and profiteers, the problem transcended region. Fraud, for example, thrived in General John Fremont’s Western Department.[7] The Confederacy, too, had low-quality garb. “I have so much marching to do that my shoes is awring out very fast and my pants is warin out as fast as my shoes is,” complained Alabamian George W.

Athey.[8]

Journalists, cartoonists, and the public condemned profiteers. “Who paid for them shoddy pants and them soft-shelled shoes?” protested James Fisk Jr., a New York financier. “Why, they were paid for by the brave men with their blood, and, by G-d, I think they had ought to had a quid pro quorum … for their outlay. The man that will take the upper hand of a soldier in the field, is worse than a thief—there’s no sand in his craw—he’s a d—-d God-forsaken, pink-eyed, white-livered scoundrel, and his cloths don’t fit him.”[9] Providing subpar products to their boys, Americans reasoned, was not just bad business, it was unpatriotic too.[10] Public outrage prompted a series of state and federal investigations in 1861 and 1862, which did effectively expose and reduce fraud in the United States.[11]

By mid-war, shoddy’s definition had metaphorized again; The Days of Shoddy, published in 1863 by Henry Morford, describes the word’s new meaning: “a synonym for miserable pretense in patriotism—a shadow without a substance.”[12] Rather than referring exclusively to products, shoddy was now applied to people as an insult. Those profiting, or perceived to be wrongly profiting, off the war became the shoddyocracy. New York City became the epicenter of the imagined crisis. In August 1862, the “Shoddyites,” wearing “new silks” and “superabundant diamonds,” visited the summer resorts at Saratoga and Long Branch. The same nouveau riche were “driving new equipages about Central Park and inspecting Brignoli through the wrong end of their new opera glasses at the Academy of Music.”[13]

Not all had fraudulently obtained their wealth and, in fact, cases of fraud declined after the war’s first year.[14] The critique, however, remained. In popular opinion, wartime consumption of the wrong sort became explicitly linked to morality and patriotism. Editorials and cartoons published during the war consistently emphasized the appearance and spending habits of the shoddyocracy. Diamonds, in particular, were deemed inappropriate items for some individuals to purchase or possess. Taking aim at conspicuous consumption, a male passenger en route to New York couldn’t help but notice “Mrs. Shoddy” and her daughters’ diamonds, which were “worth another million.” “I may be a little cynical and hard to please,” he remarked, “but it strikes me a time of carnage and death and lamentation like this is poor time for dancing and dissipation.”[15] Established northern elites continued to dress in splendor and their status, like their attire, was not questioned in this context. The main critique was not how the money was obtained, but rather who obtained it and how they spent it.

Cartoons portrayed the shoddyocracy as uncouth, uncultured New Yorkers. In particular, war profiteers spoke with a thick Irish brogue and their wives shoved oversized, workingwomen’s hands into fine kid gloves. Bearded merchants, born in foreign lands, cunningly and knowingly sold badly made goods for profit, and grew immensely wealthy as native-born soldiers died on the battlefield. Malicious stereotypes targeting New York’s Jewish merchants and Irish immigrants were common. “Once again,” concludes historian J. Matthew Gallman, “the Civil War had provided a convenient outlet for broad-based class and ethnic hostilities.”[16]

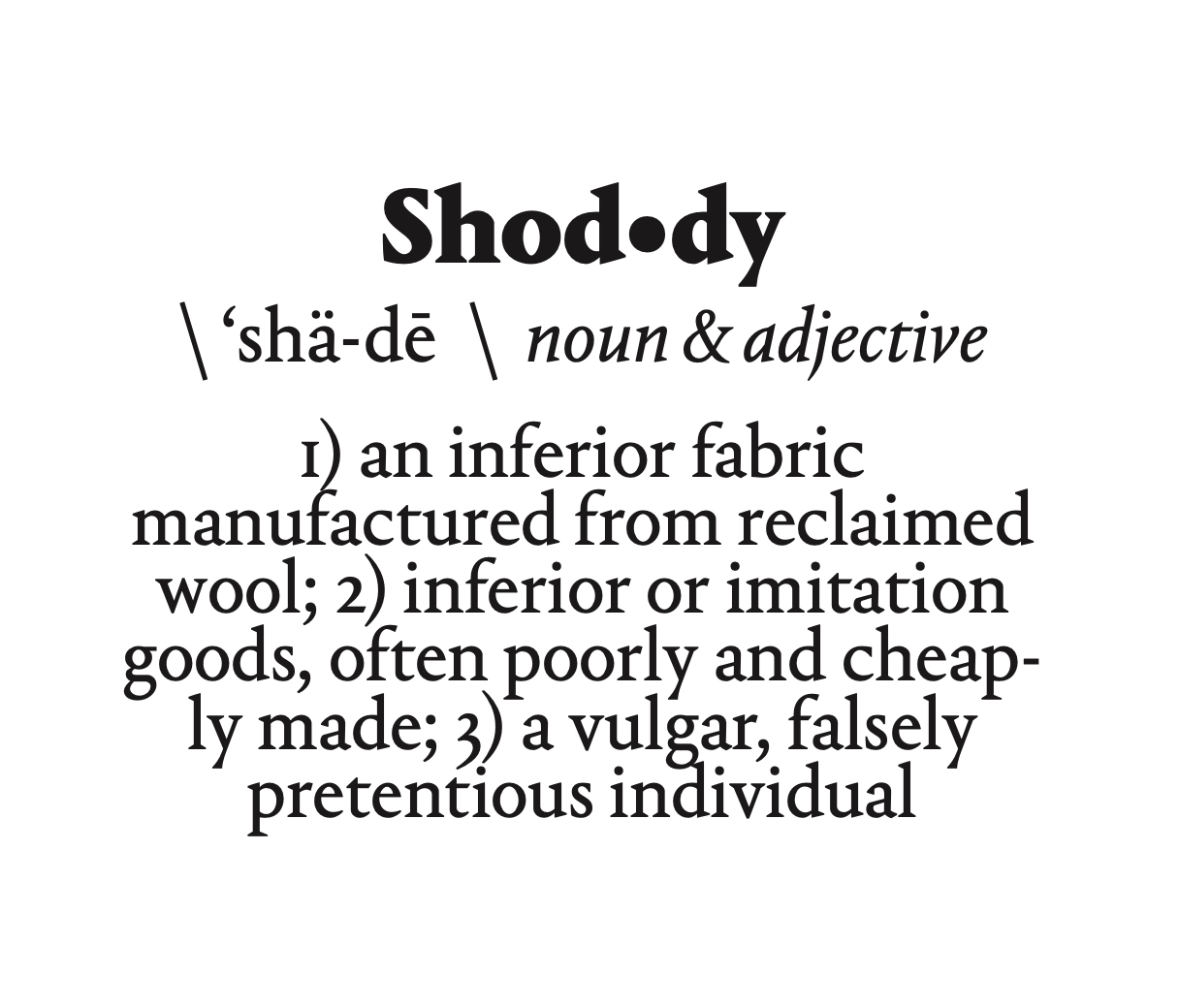

“It was during the Civil War that the word ‘shoddy’ was coined,” claimed Marian Campbell Gouverneur in her memoir of northeastern society life.[17] She is wrong only in part; the word pre-dated the conflict, but it first entered the common American lexicon in 1861. In 1862, it first appeared as an adjective in the Oxford English Dictionary: a person “that pretends to a superiority to which he has no just claim; said esp. of those who claim, on the ground of wealth, a social station or a degree of influence to which they are not entitled by character or breeding.”[18]

Over the course of just four years, the meaning of shoddy transformed from an obscure textile term into a common adjective and further into a slur—a prime example of war’s effect on language for both soldiers and civilians.

TRACY L. BARNETT IS A DOCTORAL CANDIDATE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA. HER DISSERTATION ANALYZES THE HISTORIC ORIGINS OF AMERICA’S GUN CULTURE AND ITS MUTUALLY CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONSHIP TO WHITE SUPREMACIST IDEOLOGY. AS THE DIGITAL HUMANITIES RESEARCH FELLOW, SHE WORKED AS A RESEARCH ASSISTANT FOR PRIVATE VOICES, A WEBSITE DEVOTED TO CIVIL WAR LANGUAGE.

This article appeared in the Fall 2021 (Vol. 11, No. 1) issue of The Civil War Monitor.