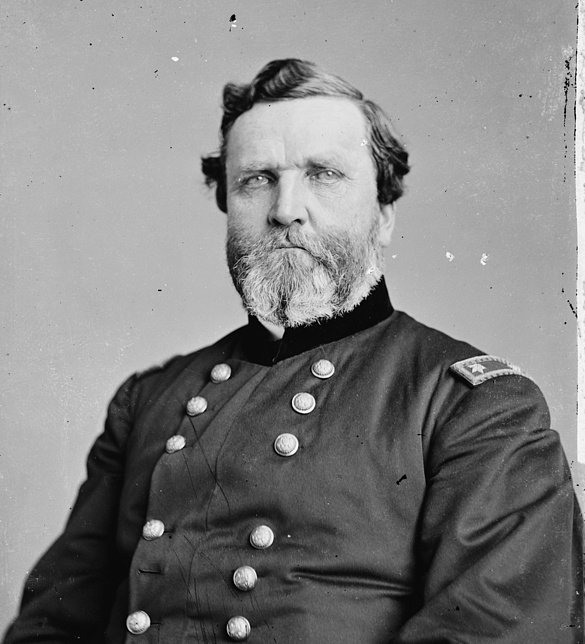

Major General George H. Thomas, the “Rock of Chickamauga”

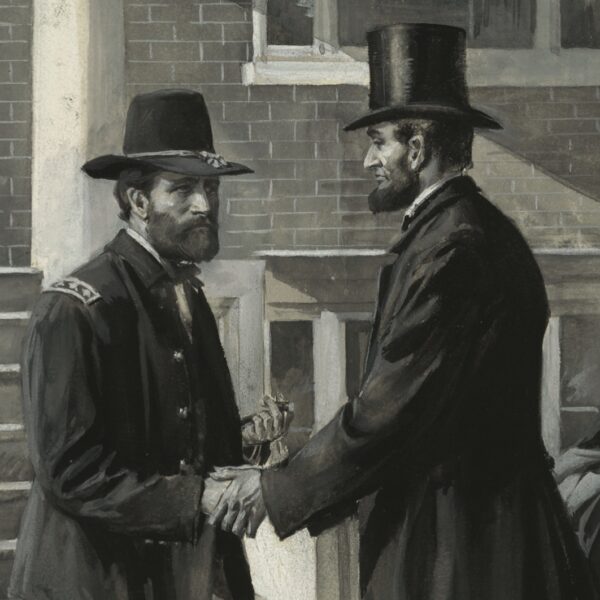

In the American Iliad, the Civil War’s chief victors are well known: Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and his partner in command, Major General William T. Sherman. Largely eclipsed by these two commanders is Major General George H. Thomas. Yet Thomas not only led one of the North’s main field armies, he was almost alone among Union generals in never losing a battle. If there is a third general with a claim to the highest place in the Union pantheon, many would argue that it belongs to Thomas.

A taciturn Virginian who had been a major in the prewar U.S. Army, Thomas was 44 years old when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter. Unlike most West Pointers who hailed from the South, he elected to remain loyal to the Union—a choice for which his siblings disowned him. (His brothers eventually reconciled with Thomas; his sisters never did.) Soon elevated to the rank of brigadier general, he achieved one of the North’s earliest victories at the Battle of Mill Springs in January 1862, which cracked the eastern flank of the Confederate defensive line in Kentucky. Thereafter he rose to command a corps, played a key role in several major battles, and in October 1863 was placed in command of the Army of the Cumberland.

Under his leadership that army achieved its greatest success. His triumph at the Battle of Nashville in December 1864 was one of the few truly decisive victories of the entire conflict. His success at the Battle of Chattanooga in November 1863 was nearly as great. His troubled relationships with Grant and Sherman, however, frequently led them to damn him with faint praise, and that is perhaps the primary reason he is not especially well known today.

Yet Thomas does occupy one prominent place in the mythology of the war: his performance on the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga, when he saved the Army of the Cumberland from likely destruction and earned a lasting nickname—“the Rock of Chickamauga.”

Fought in mid-September 1863, Chickamauga was the largest battle in the western theater and one of the bloodiest of the war. It came about in the aftermath of the almost bloodless capture of Chattanooga, Tennessee, a major rail center and the gateway into the Deep South. The seizure of the city owed to Major General William S. Rosecrans—“Old Rosy” to his men—who was then in command of the Army of the Cumberland. Rosecrans immediately continued to advance, moving south of Chattanooga into the northern fringe of Georgia. Alarmed by the loss of Chattanooga, the Confederate government heavily reinforced the Army of Tennessee, under General Braxton Bragg. Bragg began planning a counterattack, one that would pin Rosecrans against Lookout Mountain, a massive ridge that overlooked Chattanooga and ran north to south for many miles. Foiled in his initial attempts to ambush the Army of the Cumberland, which for a time was widely dispersed through two gaps in Lookout Mountain, Bragg finally brought Rosecrans to bay in a heavily wooded area only a few miles south of Chattanooga. On its eastern fringe lay Chickamauga Creek, which lent the battle its name.

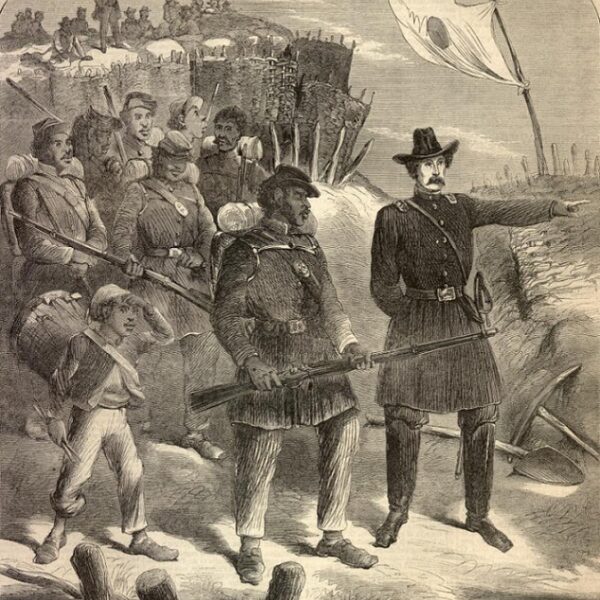

Major combat began on September 19. Bragg attacked, but although his force outnumbered the Army of the Cumberland, its attacks on the first day were uncoordinated. The Federals had little difficulty in fending off the assaults. When Bragg resumed the battle the next day it was much the same story, and the Army of the Cumberland gamely held its ground. Things went well for the Federals until a confusing order by Rosecrans opened a division-wide gap in the Union line. By unfortunate coincidence, the opening was created just as Confederate lieutenant general James Longstreet launched a heavy assault. His troops struck the Union line almost exactly at that opening and routed the northern army’s entire right wing.

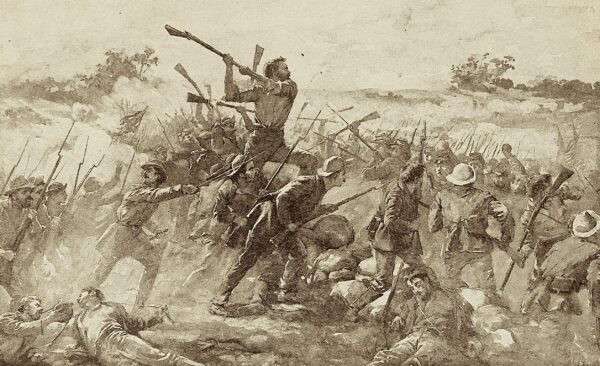

Union and Confederate troops clash during the Battle of Chickamauga is this postwar lithograph by Kurz & Allison.

Recognizing that his only hope was to get the remnants of his army to Chattanooga, Old Rosy left the battlefield to organize the city’s defense. Thomas, who led the army’s XIV Corps, took charge of the troops still organized and able to fight. The bulk of them took up a position on Snodgrass Hill, in what had been the center of the Union line. Thomas inspired the beleaguered troops with his confidence and indomitable spirit. Periodically he “would jump off his horse,” one officer recalled, “swing his hat, rush among the men and encourage them by his own acts of valor.”(1)

Brigadier General James A. Garfield, Rosecrans’ chief of staff (and future president of the United States), rode to Snodgrass Hill during the heaviest fighting, saw Thomas’ determined stand, and that evening sent a dispatch to the army commander: “General Thomas has fought a most terrific battle and has damaged the enemy badly”—so much so, he believed, that if Rosecrans sent the balance of the army to reinforce Thomas, it could still win victory the next day.(2) That message appears in the Official Records. In the lore of the battle, however, Garfield is credited with sending another dispatch during the height of the fighting. It read simply: “Thomas standing like a rock. Seven divisions intact.”(3)

Numerous historians point to this dispatch as the origin of the “Rock of Chickamauga” sobriquet, and some of them claim that the northern press quickly seized upon it. This was not the case: A computer search for the phrase in dozens of newspapers returns no hits for “Rock of Chickamauga” prior to 1869. However, evidence does suggest that by then Thomas was commonly known by that nickname. For example, at a reunion of the Army of the Cumberland in November 1870, a few months after Thomas’ death, Garfield gave a memorial oration in which he declared, “He was, indeed, the ‘Rock of Chickamauga,’ against which the wild waves of battle dashed in vain. It will stand forever in the annals of his country, that there he saved from destruction the Army of the Cumberland.”(4) The statement presumes that his listeners were already familiar with the phrase.

Although Thomas amply deserved the moniker, it has a larger significance because of the light it casts on Rosecrans. For a time Old Rosy was considered one of the North’s best generals, and until the fall of Vicksburg he was arguably more successful than Grant. Grant and Rosecrans despised each other, however, and in his memoirs Grant performed a deft but merciless hatchet job on his rival—one that has influenced our understanding of Rosecrans to this day.(5) But “Rock of Chickamauga” makes the case far more economically. It tacitly draws attention to Rosecrans’ departure from the battlefield. In the wake of the Confederate breakthrough Rosecrans was understandably shaken; still, when viewed objectively his decision to organize Chattanooga as a rally point makes sense, and he did the job effectively. Yet the choice appears fatally weak when contrasted with Thomas’ epic stand on Snodgrass Hill. In view of the fact that he held Rosecrans in high regard, then and later, this juxtaposition would have dismayed Thomas. Nonetheless, “Rock of Chickamauga” helps to frame Rosecrans in the American Iliad as a badly flawed commander, a reputation that has clung to him ever since.

Mark Grimsley, a history professor at The Ohio State University, is the author of several books, including And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May–June 1864 (2002) and The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern Civilians, 1861–1865 (1995). He has also written more than 50 articles and essays.

This article appeared in the Fall 2019 (Vol. 9, No. 3) issue of The Civil War Monitor.

(1) Quoted in Christopher J. Einolf, George Thomas: Virginian for the Union (Norman, OK, 2007), 177.

(2) Garfield to Rosecrans, September 20, 1863, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series I, vol. 30, pt. 1, 145.

(3) The alleged dispatch appears nowhere in the Official Records. The earliest source I can find for the claim is Byron A. Dunn, On General Thomas’s Staff (Chicago, 1907), 344.

(4) “Oration of General James A. Garfield, on the Life and Character of General George H. Thomas,” Society of the Army of the Cumberland, Fourth Reunion (Cincinnati, 1870), 84.

(5) All of Rosecrans’ biographers make this case, and it is argued at length in Frank P. Varney, General Grant and the Rewriting of History: How the Destruction of General William S. Rosecrans Influenced Our Understanding of the Civil War (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2013).