Library of Congress

Library of CongressSt. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond.

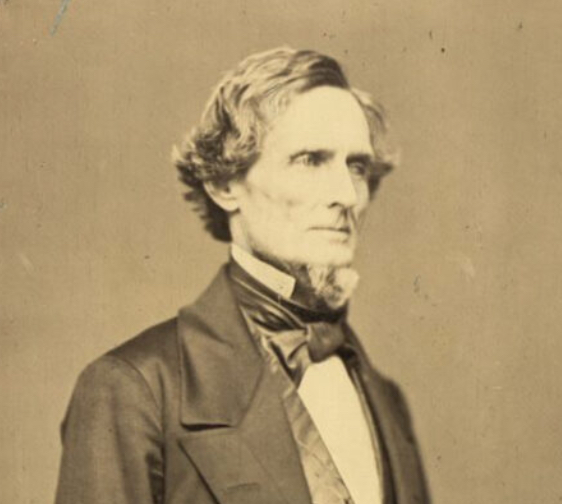

Over at Civil War Talk, there was a discussion recently about a story about Robert E. Lee, and an incident that allegedly occurred soon after the end of the war at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond. There are several slight variations of it, but this one is typical of the way it’s presented now:

One last dramatic scene awaited the rebirth of the Republic. Back in Richmond, soon after the war was over, the congregation of St. Paul’s met again for the usual Sunday services, which were to be the Episcopalian Order of Holy Communion.

The Richmond gentry and the former leaders of the Confederacy were present as usual in spite of the destruction of much of the city. When it came time for the faithful to kneel before the altar and take the Eucharistic bread and wine, a joyful young black man strode forth and knelt at the altar rail alongside the white congregants.

A silence and a gasp went across the segregated congregation. This had never happened before, and the clergy were frozen in their places not sure what to do. A black man kneeling beside a white man? It was unknown in the old South.

From the back of St. Paul’s a lone figure in a gray suit walked forward and knelt beside the freed slave. With a look of command he nodded to the priests, who gave both him and the black man Holy Communion together, eating bread from the same paten and drinking wine from the same cup.

The lone figure was Robert E. Lee, who knelt beside the man whose slavery, among other things, he had only recently fought to defend. And when the vanquished Southern commander came to the altar, the rest of the congregation followed him as well, white and black together.

A heartwarming tale of Christian brotherhood, isn’t it? It’s repeated quite a bit online, with slight variations. This example makes the case that Lee “would have been one of” the “men and women who stood with the black people of America in calling for an end to the horror of segregation.” This Baptist preacher in Louisiana goes so far to claim that Lee “reverently knelt near the black man to receive communion with him. . . , risking his own reputation and standing to help heal the rifts of Union and race.” He goes on to praise Lee’s “Christ-like spirit of grace” exhibited in that situation. The blog at the American Catholic argues that Lee “made a step that day to end” racial conflict in this country. This blogger claims the incident shows “Lee’s acceptance of the new way of life brought forth by the Union victory.”

Not quite. According to the man who claimed to have witnessed the event, it held an entirely different lesson. From the Confederate Veteran magazine, October 1905:

NEGRO COMMUNED AT ST. PAUL’S CHURCH

Col. T. L. Broun, of Charleston, W. Va., writes of having been present at St. Paul’s Church, Richmond, Va., just after the war when a negro marched to the communion table ahead of the congregation. His account of the event is as follows:‘Two months after the evacuation of Richmond business called me to Richmond for a few days, and on a Sunday morning in June, 1865, I attended St. Paul’s Church. Dr. Minnegerode [sic] preached. It was communion day; and when the minister was ready to administer the holy communion, a negro in the church arose and advanced to the communion table. He was tall, well-dressed, and black. This was a great surprise and shock to the communicants and others present. Its effect upon the communicants was startling, and for several moments they retained their seats in solemn silence and did not move, being deeply chagrined at this attempt to inaugurate the ‘new regime’ to offend and humiliate them during their most devoted Church services. Dr. Minnegerode [sic., Minnigerode] was evidently embarrassed.

General Robert E. Lee was present, and, ignoring the action and presence of the negro, arose in his usual dignified and self-possessed manner, walked up the aisle to the chancel rail, and reverently knelt down to partake of the communion, and not far from the negro. This lofty conception of duty by Gen. Lee under such provoking and irritating circumstances had a magic effect upon the other communicants (including the writer), who went forward to the communion table. By this action of Gen. Lee the services were conducted as if the negro had not been present. It was a grand exhibition of superiority shown by a true Christian and great soldier under the most trying and offensive circumstances.”

This same account, with a few very minor word changes, had been published in the Richmond Times-Dispatch the previous April; the Confederate Veteran story, while unattributed, seems to be a simple rewrite of that piece.

Apparently there’s a lot of doubt surrounding the truth of this event; I’m agnostic on whether it really happened or not. What’s genuinely telling is how, in recent years, the same basic elements of the anecdote have been twisted to make Lee some sort of early exemplar of racial harmony. But Colonel Broun sure didn’t see it that way, and the Confederate Veteran—by its masthead, the official publication of the United Confederate Veterans, the Daughters of the Confederacy, and the Sons of Confederate Veterans—didn’t either. They viewed Lee’s actions as a quiet act of defiance, a refusal to acknowledge the racial and cultural upheaval brought about by the end of the war.

It should not be a surprise that Lee would refuse to acknowledge the black man’s presence, or would find the man’s actions to be “provoking and irritating,” as Lee’s own words corroborate Broun’s interpretation of the scene. Several years before Lee had written his wife, Mary, a letter in which he inveighed abolitionist agitators who would “Create angry feelings in the Master,” an “evil Course” that would ultimately work to the detriment of those enslaved. As for the “peculiar institution” itself, Lee found it to be an unpleasant burden on both blacks and whites, but nonetheless a practice established as part of God’s unknowable plan. “How long their subjugation may be necessary,” Lee wrote, “is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.” Lee himself saw no end to the practice of chattel bondage, as unpleasant as it was, nor any proper role for mere human institutions to interfere with it:

The doctrines & miracles of our Saviour have required nearly two thousand years, to Convert but a small part of the human race, & even among Christian nations, what gross errors still exist! While we see the Course of the final abolition of human Slavery is onward, & we give it the aid of our prayers & all justifiable means in our power, we must leave the progress as well as the result in his hands who sees the end; who Chooses to work by slow influences; & with whom two thousand years are but as a Single day.

In the meantime, Lee argued, the institution of slavery was beneficial to those enslaved. “The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically,” he wrote, and “the painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things.”

There is nothing unusual about Lee’s attitude toward slavery in this long passage; it approximates the views that were common among men of Lee’s class of wealthy Virginia patricians. (Lee was not wealthy himself, thanks to his father’s profligate spending, but he nonetheless moved in those same circles.) But neither are these the views of a man who, a few years later, would be likely to willingly take communion at the rail next to a man who, not long before, had likely been a slave, a man who (in Lee’s view) should have rightly remained under white rule as “ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.” It defies credulity to believe that Lee, a man who owned slaves personally for most of his adult life, and had spent virtually his entire life deeply embedded at the top of a Virginia society inextricably enmeshed with the practice, would suddenly embrace a “new way of life brought forth by the Union victory.”

None of this is to say that Lee was a monster, but only that he was a man, subject to the same attitudes and biases in his day that we all are in ours. But it seems clear that Broun gauged Lee’s actions correctly; his presence at the communion rail reflected defiance and disdain for the black man’s actions, not an embrace of them in the mutual brotherhood of Christ.

Modern-day Confederate heritage advocates are continually railing against “revisionism” in history, but even a casual glance reveals the whole Lost Cause narrative itself to be a revisionist tale, carefully crafted in the decades after the end of the war, and little changed since then. This case is a little different, an anecdote from the first decade of the last century, as the Lost Cause narrative neared its zenith, reiterating the Marble Man’s defiance of the new order and refusing to acknowledge a black man as an equal, even briefly at the altar in the eyes of his God and his church. That’s not an acceptable message now, of course, so—not unlike the “faithful slaves” of a century ago who’ve more recently been transformed into patriotic “black Confederates” for a modern audience—Lee’s actions have now been spun to fit a 21st century narrative of Christian benevolence, racial tolerance and brotherhood.

Hogwash. Revisionism is as revisionism does, y’all.

Andy Hall is a Texan and Southerner by birth, residence and lineage, with a family tree full of butternuts. With a background in history, museum studies and marine archaeology, Hall also writes at his own blog, Dead Confederates.