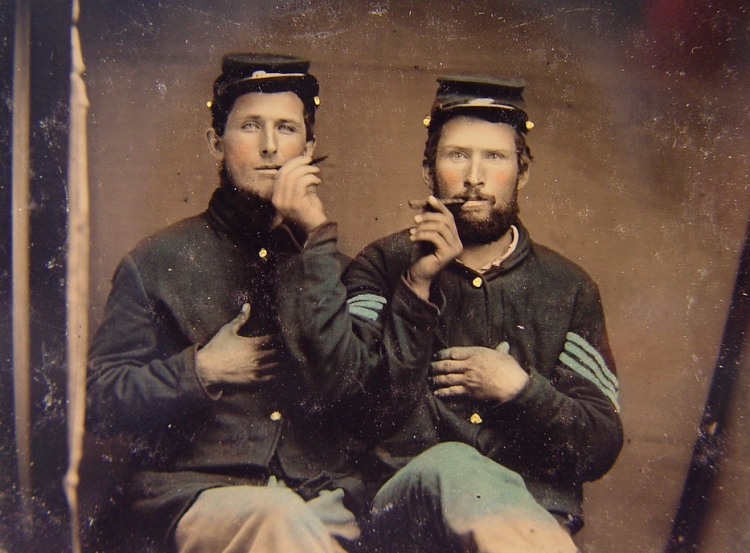

In the Voices section of the Spring 2018 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted first-person quotes from Union and Confederate troops about the use of tobacco among soldiers and civilians. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that didn’t make the cut.

“I’m sorry you feel so bad about my smoking. I think, after you had spent a night or two on picket and saw the comfort the soldiers draw from a pipe or cigar as they sit round the fire, you would say, ‘I forgive you—smoke, at least while you are in the army.’”

—Oliver Wilcox Norton, 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry, in a letter to his cousin, February 27, 1862

“The boys are greatly in need of tobacco, but I managed to get a handkerchief full of smoking—you know I don’t chew—while out foraging on my own hook; it was a good thing I can assure you. Some of the captains supply the men from company funds, and Captain Partridge buys it himself, and trusts the men until they are paid. Our captain has company funds, but is so mean, he will not use it for any thing. He has never done any thing for the men, by which he would spend a cent of his own money.”

—Alfred Davenport, 5th New York Infantry, in a letter to his mother, April 21, 1862

“Saw Wardell to-day, and he gave me some tobacco, which ‘saved my life’ for 24 hours at least.”

—Andersonville prisoner Eugene Forbes, on an encounter with a fellow POW, in his diary, November 15, 1864

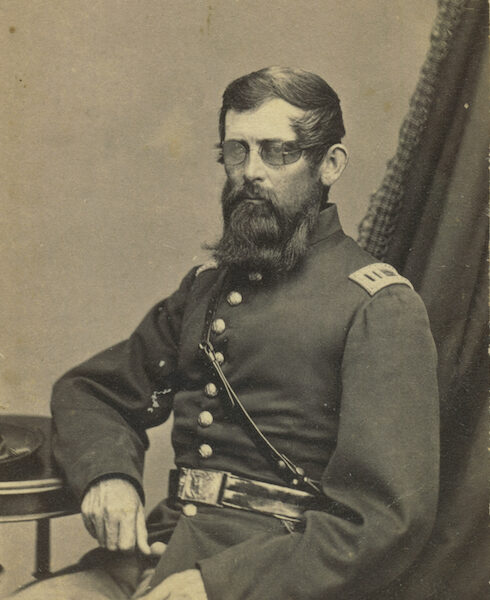

Captain William Thompson Lusk, 79th New York Infantry

“I have given up smoking. Think of that! You see, at first, when I found there was little to do, I smoked vigorously to pass away time. But when the cigar was smoked, there was an end to the amusement, so I then determined to break off smoking altogether, and, to make it exciting, I kept a handful of cigars in my pocket so that the temptation might be frequently incurred. Whenever I longed for a fragrant Havana, I would take one in fingers, and then sitting back in my chair, reason philosophically on the pernicious effects of tobacco. On reaching the point of conviction, I would return it to my pocket unlighted. This, you see, has afforded me a very excellent pastime.”

—Captain William Thompson Lusk, 79th New York Infantry, in a letter to his mother, July 10, 1863

“It would be difficult to find elsewhere than at this place a collection of two hundred and fifty women so unkempt, frowzy, ragged, dirty, and altogether ignorant and wretched. Some of them were chewing tobacco; others, more elegant in their tastes, smoked. Another set indulged in the practice of ‘dipping.’ Sights like these soon put to flight our rosy ideals.”

—Union staff officer George Ward Nichols, on encountering the female workers at the Saluda Factory in Columbia, South Carolina, in his diary, February 16, 1865

“Tobacco, in all its forms, seems indispensable, by reason of the moral courage with which it is supposed to inspire alike the soldier and the civilian. This article is laid in by the men whenever and as often as occasion presents. In our great country it has all sections for its own. It is certain that the war is going to give an immense permanent stimulus to the consumption of this standard narcotic.”

—Private Louis Richards, 2nd Pennsylvania Emergency Militia, in his diary, September 15, 1862

“We could go out to the fire at any time of night we pleased … and we would always find half a dozen of the boys sitting about the fire-logs, smoking their pipes, telling yarns, or singing snatches of old songs.”

—William Bircher, 2nd Minnesota Infantry, in his diary, December 24, 1864

“Run across a dead Johnny; went through his pockets, found a plug of Virginia leaf tobacco. By his side lay a small bag of flour. Appropriated both, and that night had some flour fritters mixed with water, and a good smoke. Such is war!”

—Henry Warren Howe, 13th Massachusetts Infantry, in his diary, September 24, 1864

“It is a pleasant sight to look on a group sitting round a fire in the evening, whiling away the time with stories of the past and speculations of the future. Then you would always see the pipes there. That you wouldn’t like. But for some reason a soldier does enjoy his tobacco. A count was made the other day of the men in our company who use tobacco and of the eighty-seven present sixty-one fell under the ban. I think that a fair average of the regiment. Since we came here the boys have gone to making pipes of the laurel roots that grow on the old breastwork thrown up in the Revolution. I have one that I think a great deal of.”

—Oliver Wilcox Norton, 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry, in a letter to his cousin, May 1, 1862

“Tobacco scarce, prices high; men will as surely have it as they can get it. This proves the strength of the habit of its use; but the use of it does not prove the theory propagated by users, that it prevents scurvy in the mouth. It is extensively used, but I notice that scurvy in the mouth is as common among chewers as non-chewers. Eight out of ten of my company who use tobacco, have scurvy. Most of those who have died used it; several of those alive are toothless because of diseased gums. I know of an inveterate chewer whose cheeks are badly swollen who still munches it, if he can get it, and expectorates blood and matter and tobacco juice. In these cases it may only irritate parts affected and add poison to disease. Smoking is more consistent; the fumes of burning tobacco are more preferable than diseased atmosphere. I think it tends to purify it from pestilence. Smokers resort to gathering quids that have been chewed, dry them in the sun, pulverize, then burn it in their pipes.”

—Andersonville prisoner John W. Northrop, in his diary, August 27, 1864

“I think I shall quit the use of tobacco altogether, as I am inclined to believe that it injures me.”

—First Lieutenant Elisha F. Paxton, 4th Virginia Infantry, in his diary, August 18, 1861. Paxton would rise in rank to brigadier general and be killed in May 1863 at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

“Snuff-dipping is an universal custom here, and there are only two women in all Iuka that do not practice it. At tea parties, after they have supped, the sticks and snuff are passed round and the dipping commences. Sometimes girls ask their beaux to take a dip with them during a spark. I asked one if it didn’t interfere with the old-fashioned habit of kissing. She assured me that it did not in the least, and I marveled.”

—Illinois soldier Charles Wright Wills, on the women of Iuka, Mississippi, in his diary, June 9, 1862

“The other day I was at the Christian Commission, and they were distributing a large number of beautiful medals, on which was inscribed the pledge ‘Rum and tobacco I’ll not use, Nor take God’s name in vain,’ etc. I went directly to the Sanitary Commission, and found them issuing large quantities of tobacco free to the boys! Which is right?”

—Union chaplain Hallock Armstrong, in a letter to his wife, March 23, 1865

“The passion for tobacco among our men continues quite absorbing, and I have piteous appeals for some arrangement by which they can buy it on credit, as we have yet no sutler. Their imploring, ‘Cunnel, we can’t lib widout it, Sah,’ goes to my heart.”

—Thomas Wentworth Higginson, colonel of the 1st South Carolina Infantry, a regiment comprised of former slaves, in his diary, December 16, 1862

“The women here have a filthy habit of snuff chewing or dipping as they call it, and I am told it is practiced more or less by all classes of women. The manner of doing it is simple enough; they take a small stick or twig about two inches long, of a certain kind of bush, and chew one end of it until it becomes like a brush. This they dip into the snuff and then put it in their mouths. After chewing a while they remove the stick and expectorate about a gill, and repeat the operation. Many of the women among the clay-eaters chew plug tobacco and can squirt the juice through their teeth as far and as straight as the most accomplished chewer among the lords of creation.”

—David L. Day, 25th Massachusetts Infantry, on the women of New Bern, North Carolina, in his diary, April 20, 1862

“I have quit chewing tobacco from necessity. I can not procure the weed at any price, so I thought that it was as good a time to quit as I will ever find. Probably I will not chew any more. I can break myself of any habit I desire to, I believe.”

—Confederate surgeon Junius Bragg, in a letter to his wife, July 30, 1863