Roosters prepare for battle in a Union army camp.

In the Voices section of the Fall 2021 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about nicknames. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“I looked and poor Fed was dead. The other rooster had popped both gaffs through his head. He was a dead rooster; yea, a dead cock in the pit.”

—Samuel R. Watkins, 1st Tennessee Infantry, on the death of a comrade’s rooster during a cock fight, in his memoirs. It “was named Southern Confederacy; but this was abbreviated to Confed., and as a pet name, they called him Fed,” noted Watkins.

“They were nicknamed by the people and soldiers ‘featherbeds,’ because they always scattered at night and slept in their own or other people’s houses, and were usually safe in doing so, as raids were seldom made at night.”

—Frank Alexander Montgomery, 1st Alabama Cavalry, on the local Mississippi troops of Major W.E. Montgomery, who were “considered by the federals as guerrillas,” that he and his comrades faced, in his memoirs

“There was in the battalion a simple-witted fellow nicknamed Possum. This man planted himself in front of General Lee, and, looking up into his face, grinned and said, ‘Howdy do, dad?’ General Lee, roused from his reverie, looked up, and, in a kindly sad voice, answered, ‘Howdy do, my man?’ and rode on.”

—Confederate soldier Royall W. Figg, on an incident that reportedly occurred between Robert E. Lee and one of his soldiers shortly after the 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor, in his memoirs

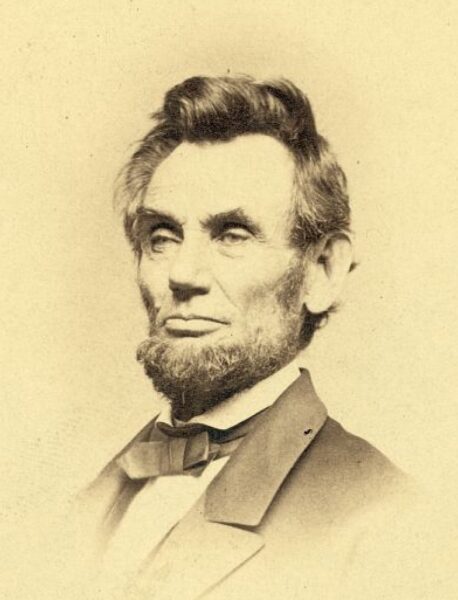

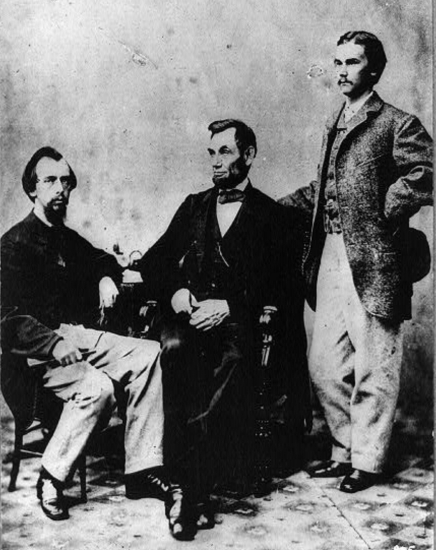

Abraham Lincoln (center) with secretaries John Hay and John Nicolay

“As the Ancient was in bed I volunteered to receive the harrowing communication.”

—John Hay, personal secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, using a nickname he had for the president, in his diary, April 1861. Actress Jean Margaret Davenport had arrived around midnight on April 19 to report a rumor that several men had planned to kill or capture the president, who was asleep.

“Started on our return at 8 o’clock, with drove of cattle and horses. Major and Purps went ahead, and a few miles from the road, to a deserted camp and got a secesh wagon, old style, hitched in four horses and had a gay time. Lead horses whirled after a time and broke the tongue, fixed it and with two horses drove through the camp. Horses balked several times, once in the river. Hadley and I undressed and helped across.

Command stopped at Hudson’s. Jayhawked the people badly. (‘Purps’—nickname for noncommissioned staff.)”

—Luman Harris Tenney, 2nd Ohio Cavalry, in his diary, June 8, 1862

“We have an energetic man near us, nicknamed ‘Slick.’ His name is Brown, from Georgia. He was confined with us at Andersonville. He left his home to escape Rebel rule, and joined the army of the Cumberland; has been a prisoner ten months…. His expressions against the Rebel cause are bitter. For a while during the summer he was placed in a dungeon. He goes outside to chop. On return at night choppers are searched, not allowed to bring in anything except wood or a bundle of wild grass, unless they buy it of the sutler. Citizens are forbidden. ‘Slick’ and one other I know, make a sly trade now and then, and splitting a large piece of pine they scoop out one of the halves in the form of a trough, and frequently bring in a peck of beans or potatoes or something that fits the cavity, concealed by replacing the pieces.”

—Andersonville prisoner John Worrell Northrop, in his diary, November 17, 1864

Andersonville Prison

“I don’t think that one man in a thousand thought it possible for a person to escape to the Union lines, even if he was outside the stockade. My tent mates often chaffed me for thinking I could get away and they nicknamed me Dick Turpin.”

—Andersonville prisoner Thomas Hinds, in his memoir of the war. Dick Turpin was an 18th-century English criminal who was romanticized as the wily “Knight of the Road” in popular culture in the decades after his execution for horse theft.

“A curious little Irishman in our company, nicknamed ‘Dublin Tricks,’ who was extremely awkward, and scarcely knew one end of his gun from the other, furnished the occasion of another outburst of laughter, just when the bullets were flying like hail around us. In his haste or ignorance, he did what is often done in the excitement of rapid firing by older soldiers: he rammed down his first cartridge without biting off the end, hence the gun did not go off. He went through the motions, putting in another load and snapping his lock, with the same result, and so on for several minutes. Finally, he thought of a remedy, and sitting down, he patiently picked some priming into the tube. This time the gun and Dublin both went off. He picked himself up slowly, and called out in a serio-comic tone of voice, committing the old Irish bull, ‘Hould, asy with your laffin’, boys; there is sivin more loads in her yit.’”

—Confederate soldier William G. Stevenson, in his memoirs

“The officers of the Army of the Cumberland were assigned to the middle rooms of the second and third stories. The lower and middle room was used as a general kitchen, and the basement immediately below was fitted up with cells for the confinement and punishment of offenders. These rooms received the sobriquet of ‘Chickamauga.’”

—Wisconsin officer Harrison Carroll Hobart, who had been among the captured Union soldiers sent to Libby Prison in Richmond after the Battle of Chickamauga, in his memoirs

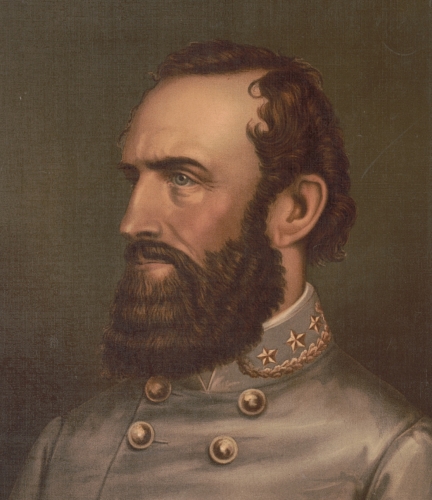

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson

“The enemy has taken a position, or rather several positions, on the Fauquier side of the Rappahannock. I have only time to tell you how much I love my little pet dove.”

—Confederate general Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, in a hurried note to his wife, Mary, a few days before the Second Battle of Bull Run, August 25, 1862

“The nurses can do nothing with him. He cannot talk plain, and if they do not understand the first time, he flies into a rage and curses them soundly. The first time he called on me to dress his wound he snatched the dish from my hand…. The next day he asked me to warm some water to dress his wound. No, said I, I will have nothing to do with you until you can treat me as one man should treat another…. In a day or two he came to me and asked, very civilly, if I would try and get him some tea, as his mouth was so bad he could eat nothing. ‘With pleasure,’ said I. From that day he is my fast friend. The boys call him ‘the boss’s pet tiger.’”

—David Lane, 17th Michigan Infantry, on one of his patients—an “old fellow … sounded through the cheeks … [and] as cross as a grizzly, ferocious as a hyena”—while he was on detail for hospital service at the United States General Hospital in Knoxville, in his diary, January 6, 1864

“The shot and shell fell all around us, throwing up showers of red dirt, but doing no harm. While these guns were thus engaged, I noticed a large, fine-looking man, mounted on an iron gray horse, near one of the pieces, and who was intently watching our advance across the field. He evidently was a Confederate officer, and I thought possibly of high rank; so, taking careful aim each time, I gave him two shots from ‘Trimthicket’ (the pet name of my old musket,) but without effect, so far as was perceivable.”

—Leander Stillwell, 61st Ohio Infantry, on an incident during the Battle of Wilkinson’s Pike, December 7, 1864, in his memoirs. Captured Confederates informed Stillwell after the battle that the officer he had shot at was Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest

“The five hundred men of the Third Regiment who accompany us … are known … as the ‘men in mourning.’”

—Zenas T. Haines, 44th Massachusetts Militia, on what they called the soldiers of the 3rd Massachusetts Militia, who wore black overcoats, while both regiments were transported to war by steamship, in a letter home, October 23, 1862

“Thereafter Kill-cavalry (as scoffers call him) gave us a charge of the 500, which was entertaining enough, but rather mobby in style.”

—Union staff officer Theodore Lyman, on the appearance of cavalry commander Hugh Judson Kilpatrick during a review of the Army of the Potomac’s II Corps, in a letter to his wife, February 24, 1864

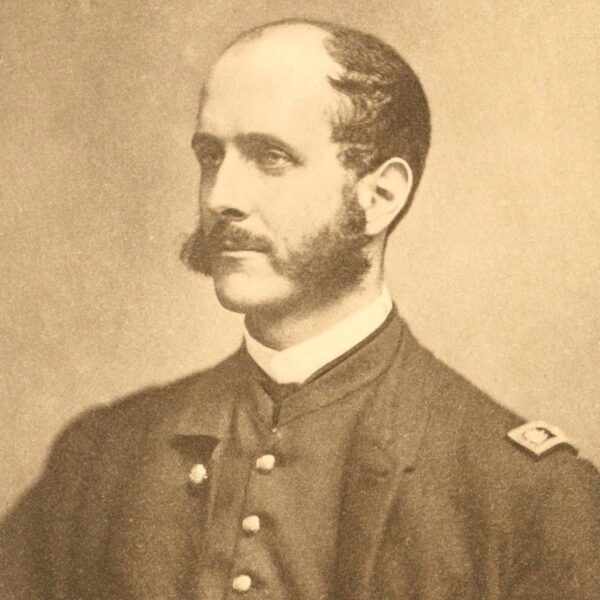

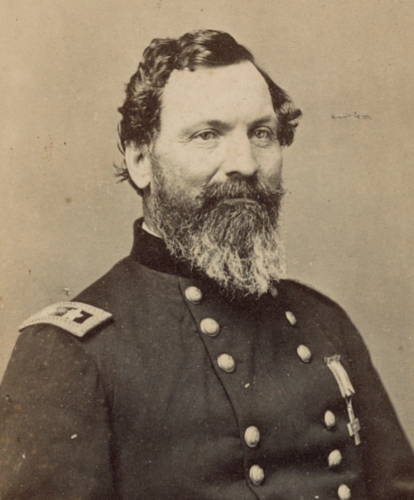

Union general John Sedgwick

“He has a magnificent profile, well cut, with the nose and forehead forming almost a straight line, curly, short chestnut hair and full beard, cut short, with a little gray in it. He dresses carelessly … and is honest and modest. You might see at once why his men, because they love him, call him ‘Uncle John,’—not to his face of course, but among themselves.”

—Union officer Franklin A. Haskell, on Major General John Sedgwick, in his diary, July 16, 1863

“Our Corps, the 8th, also known as the Army of West Virginia, the Mountain Creepers, Foot Cavalry, and the Buzzards, so called by its making so many forced marches over the mountains and valleys of Virginia.”

—Charles H. Lynch, 18th Connecticut Infantry, on the nicknames given to the Union army’s VIII Corps, in his diary, August 16, 1864

“We called him ‘rough diamond,’ as he is so rough-looking, and seems to have such a kind heart. He thinks nothing a trouble which he has to do for the wounded.”

—Confederate nurse Kate Cumming, on a Dr. Wellford from Fredericksburg, Virginia, who had arrived to help treat soldiers wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga, in her diary, December 25, 1863

“The affection his soldiers bore him has always been an enigma…. His strong religious bent, his devotion to a form of religion the most gloomy—for his Calvinism amounted to very little less than fatalism, and his men called him ‘old bluelight’—his strictness of life, and his utter lack of vivacity and humor, would have been an impassable barrier between any other man and such troops as he commanded.”

—Confederate soldier George Eggleston on the affection the men had for Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, in his memoirs

“There was an inferior looking Frenchman at our review the other day, highly adorned with decorations, and gold lace, who is a mystery as yet. He is some sort of a foreign Prince. Our boys call him ‘Slam Slam.’”

—Rufus Dawes, 6th Wisconsin Infantry, on a recent review of the Army of the Potomac, in a letter to his sister, Fall 1861

Sources

Co. Aytch (1900); Reminiscences of a Mississippian in Peace and War (1901); Where Men Only Dare to Go! (1885); The Life and Letters of John Hay (1915); War Diary, 1861–1865 (1914); Chronicles from the Diary of a War Prisoner … (1904); Tales of War Times (1904); Thirteen Months in the Rebel Army (1862); War Papers, Read Before the State of Wisconsin (1891); Life and Letters of General Thomas J. Jackson (1891); A Soldier’s Diary (1905); The Story of a Common Soldier (1920); Letters from the Forty-Fourth Regiment M.V.M. (1863); Meade’s Headquarters, 1863–1865 (1864); The Battle of Gettysburg (1898); The Civil War Diary … of Charles H. Lynch (1915); Kate: The Journal of a Confederate Nurse (1998); A Rebel’s Recollections (1875); Service in the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (1890).