A coffee cup used during the Civil War

In the Voices section of the Winter 2020 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about the importance of coffee to the troops. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that didn’t make the cut.

“[W]e halted … and, stacking arms, began to boil our coffee, the favorite occupation of the soldiers upon all occasions when a halt is ordered….”

—Captain Augustus C. Brown, 4th New York Heavy Artillery, on his unit’s pausing en route to the Battle of the Wilderness, in his diary, May 6, 1864

“Sometimes, where companies preferred it, the rations were served out to them in the raw state; but there was no invariable rule in this matter. I think the soldiers, as a whole, preferred to receive their coffee and sugar raw, for rough experience in campaigning soon made each man an expert in the preparation of this beverage. Moreover, he could make a more palatable cup for himself than the cooks made for him; for too often their handiwork betrayed some of the other uses of the mess kettles to which I have made reference. Then, again, some men liked their coffee strong, others weak; some liked it sweet, others wished little or no sweetening; and this latter class could and did save their sugar for other purposes.”

—Massachusetts artillerist John D. Billings, in his memoirs

“I wish you to buy, and forward by express, a large coffee-roaster, which will roast thirty or forty pounds at a time. There is a kind, I am told. It would be of immense advantage to us.”

—Wilder Dwight, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter to his parents, August 31, 1861. Two weeks later, he wrote, “Coffee-roaster has arrived, and is merrily at work. This is a comfort. Tell father he is the regiment’s friend, and I bless him.”

“As the Battery boys had not had much time the whole day long for anything but fighting and watching, their stomachs had not been cared for. I asked some of the staff officers if the men could not make coffee. They said, ‘You can do so at your own risk.’ A sheltered place, where, it was thought, the light could not be seen, was soon found and a fire started. The coffee was just boiling, when the order came to march at once. The temptation was too great; the men all came running up, cup in hand, dipped the cup into kettle, then ran to their several places each with a cup full of boiling hot coffee. While they were mounting their horses, I heard on all sides, various exclamations; such as, ‘But this coffee is hot!’ ‘How I burned my mouth!’ ‘Whoa, pet, I did not mean to burn you!’ I was powerless; I could not order them to throw the coffee away, for I knew what a precious boon it was to those tired and worn men.”

—New York artillerist Jacob Roemer, in his memoirs

“Coffee was their staff of life, and they must have it, no matter what risk attended. The most disheartening event that could happen a soldier was to be called into line just as his coffee pot was beginning to bubble.”

—Fenwick Hedley, 32nd Illinois Infantry, in his memoirs

“The individual coffee-boiler of one man in the Army of Northern Virginia was always kept at the boiling point. The owner of it was an enigma to his comrades. They could not understand his strange fondness for ‘red-hot’ coffee. Since the war he has explained that he found the heat of the coffee prevented its use by others, and adopted the plan of placing his cup on the fire after every sip.”

—Carlton McCarthy, a private in the Richmond Howitzers, in his memoirs

“[A]s a whole our rations were sound and wholesome. The coffee was especially good, and was in fact the soldier’s main stay. What we each man drank at every meal would keep a New England family a day, but in the open air it did not hurt us, and it was a constant comfort.”

—Charles Bardeen, 1st Massachusetts Infantry, in his memoirs

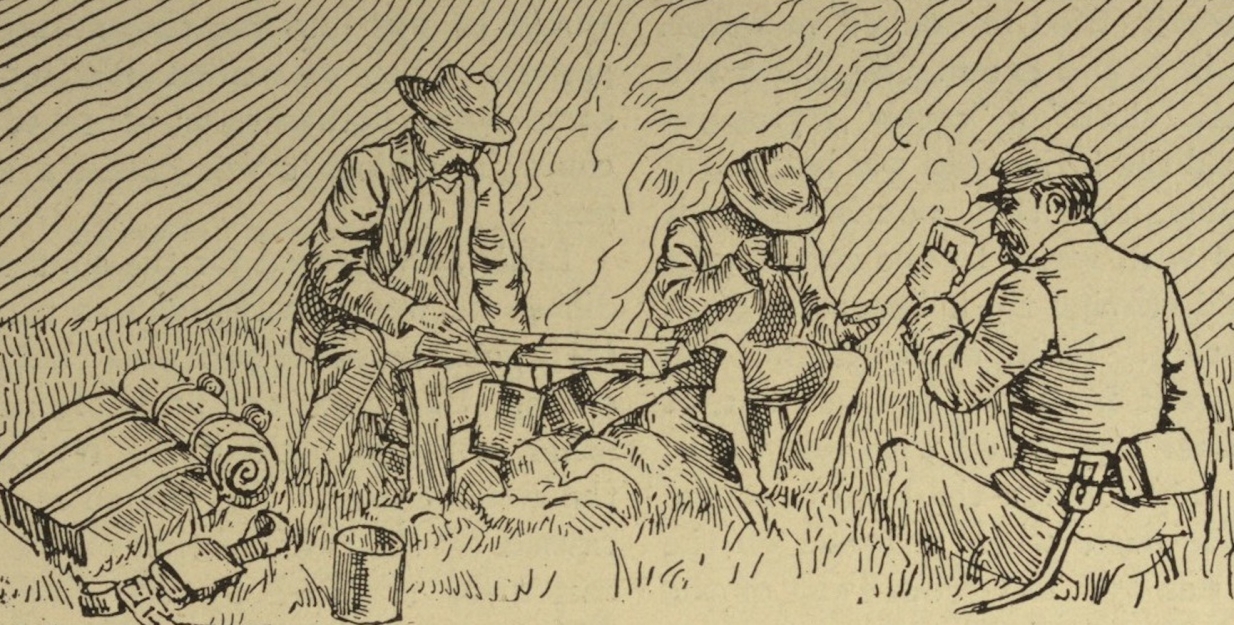

“There is a good deal of complaint, in our company at least, about the coffee we get. It seems not quite so good as that we have had, and I suspect it has been adulterated by somebody who is willing to get rich at the expense of the poor soldier, whose curses will be heaped strong and heavy on anybody who deteriorates any of his rations, and particularly his coffee. The only time a soldier can not drink his coffee is when the use of that ration is suspended. In fact, there is nothing so refreshing as a cup of hot coffee, and no sooner has a marching column halted, than out from each haversack comes a little paper sack of ground coffee, and a tin cup or tin can, with a wire bale, to be filled from the canteen and set upon a fire to boil. The coffee should not be put in the water before it boils. At first I was green enough to do so, but soon learned better, being compelled to march before the water boiled, and consequently lost my coffee. I lost both the water and the coffee. It takes but about five minutes to boil a cup of water, and then if you have to march you can put your coffee in and carry it till it is cool enough to sip as you go. Even if we halt a dozen times a day, that many times will a soldier make and drink his coffee, for when the commissary is full and plenty, we may drink coffee and nibble crackers from morning till night. The aroma of the first cup of coffee soon sets the whole army to boiling; and the best vessel in which to boil coffee for a soldier is a common cove oyster can, with a bit of bent wire for a bale, by which you can hold it on a stick over the fire, and thus avoid its tipping over by the burning away of its supports.”

—Osborn Oldroyd, 20th Ohio Infantry, in his diary, June 20, 1863

“Last Monday the Yanks condemned a barrel of green coffee and turned it over to us. It smelled awfully, but we scalded it, then toasted it and now drink it with avidity.”

—Confederate prisoner Henry C. Dickinson, in his diary, January 19, 1865

“Fine, cool morning. Drew rice, meat, beans, flour, hominy and beef. Nothing new of importance. Some rascal stole my coffee pot.”

—Andersonville prisoner Philip Koempel in his diary, September 16, 1864

“We marched up the river road about 18 miles, getting into camp late in the evening, having met with no obstacles during the day. Here again was a scramble for rails and wood for fires; all the rails near by were gone, and we had to tote ours about a quarter of a mile. The fires kindled, making coffee was in order; after a twenty mile tramp and toting rails for fires, as they stood around them, roasting one side and freezing the other, the boys are not feeling very amiable. If there is any one thing more than another that will draw the cuss-words out of them, it is when a dozen cups of coffee are sitting along a burning rail boiling, and some careless fellow comes along, hits the end of the rail, dumping it all over. It is not the loss of the coffee they care so much about, but it is going perhaps half a mile for water to make more.”

—David L. Day, 25th Massachusetts Infantry, in his diary, December 1862

“During the existence of the war, coffee was a luxury in which only the most wealthy could constantly indulge; and when used at all, it was commonly adulterated with other things which passed for the genuine article, but was often so nauseous that it was next to impossible to force it upon the stomach. Rye, wheat, corn, sweet potatoes, beans, groundnuts, chestnuts, chiccory, ochre, sorghum-seed, and other grains and seeds, roasted and ground, were all brought into use as substitutes for the bean of Araby; but after every experiment to make coffee of what was not coffee, we were driven to decide that there was nothing coffee but coffee, and if disposed to indulge in extravagance at all, the people showed it only by occasional and costly indulgence in the luxurious beverage.”

—Richmond resident Sallie Brock Putnam, in her memoirs

“Soon after our arrival on board the boat coffee was prepared for us. It was made in a large barrel, by steam. Oh, but that sweet odor from the coffee was delicious. It testified that we had passed from a land of starvation to a land of plenty. We had not smelled coffee for about six months until now, and were receiving our first meal from Uncle Sam since our exchange.”

—Henry Harrison Eby, 7th Illinois Cavalry, on returning to Union lines after his release from a Confederate prison, in his memoirs

“We were in a great strait for coffee, which, for a long time, seemed utterly out of the question. At length, however, Joe Pray, a ‘cute’ genius, was inspired. Just in front of my place rose the escape-pipe of the steamer, ten or twelve feet above the deck: from this, hot steam was constantly issuing. Joe was seen to eye this, to grow thoughtful, then to pour a handful of ground coffee into his canteen, partly filled with water. With this he came to the foot of the pipe; and, after a few efforts, he tossed the canteen clear over its edge into the current of steam, holding it by its long white string. It was an entire success. Joe withdrew in a few minutes with a canteen full of hot, well-steeped drink. As he squeezed his way back to his place, there was a crowd to profit by his experiment. The old pipe puffed away, and many were the coffee-makers who invoked blessings upon the head of Joe Pray.”

—James K. Hosmer, 52nd Massachusetts Infantry, on the ingenuity of a comrade while the regiment was aboard the transport St. Mary’s, in his diary, April 21, 1863

“[It’s] the soldier’s chiefest bodily consolation.”

—Zenas T. Haines, 44th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, on the importance of coffee to the troops, in a letter home, October 23, 1862

“As the regiment was going to move in light marching order at daylight, I got up and hunted for some coffee. I was lucky enough to find one house pretty well supplied, and engaged them to make me ten gallons for our company. We were very fortunate in getting this, as it enabled the men to start off feeling warm and comfortable, which is a great thing.”

—Charles F. Morse, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter home from Charlestown, Virginia, March 2, 1862

“[E]ach man is permitted to cook his rations in his own way, and so every man has a frying pan of some sort, and a tin peach can in which to boil his coffee. One man in our company, ‘Long John,’ as the boys have nicknamed him, is a great coffee drinker. He carries a two-quart peach can strapped to his haversack, and every day buys up one or two rations of coffee from the boys who do not use much.”

—Alexander G. Downing, 11th Iowa Infantry, in his diary, August 18, 1862

“To make coffee on the march, the boys provide themselves with an empty tin can with a wire stretched across the top for a bail. They put the coffee and water in this little can which they carry with them, and holding it on a stick in the flame of a camp fire, soon have coffee boiling.”

—Oscar Lawrence Jackson, 63rd Ohio Infantry, in his diary, September 20, 1862

“[D]uring the winter months, when we needed some kind of beverage to wash down our hardtack, the only thing we could get was horse feed, which was roasted and boiled. We called it coffee. It was very good then. We had to rob our horses for this, and we all felt mean when we did it.”

—Luther W. Hopkins, 6th Virginia Infantry, in his memoirs

“The good understanding between the pickets went so far that during the evenings there was a regular trading of the tobacco of the Confederates for the coffee of the Federals. Coffee was an abundant and daily ration for our men. To the Southern soldier, who had had none since the war began, it was a delicious luxury. They met each other without arms, in a little ravine near a spring from which they drank in common. They traded the New York for the Richmond journals, and often they drank their coffee together, while making their barter. The most severe orders were necessary to suppress those polite attentions, and break up these clandestine meetings.”

—Union officer Régis de Trobriand, in his memoirs

“That night, I remember, every man of the command had coffee in abundance, for so closely had we pursued that the enemy had thrown away many haversacks and bags of rations they had.”

—Frank Alexander Montgomery, 1st Mississippi Cavalry, on an incident during the Atlanta Campaign, in his memoirs

“We are reduced to about quarter rations, and no coffee, and nobody can ‘soldier’ without coffee.”

—Ebenezer N. Gilpin, 3rd Iowa Cavalry, in his diary, April 28, 1865

“Come to think of it, my prettice, you must have been up all night to have made up and sent out such a basket of goodies, and baked and buttered such a lot of biscuits, and made so many jugs of coffee as came this morning. My, I tell you it all tasted good, and the coffee—well, no Mocha or Java ever tasted half so good as this rye-sweet-potato blend! And think of your thoughtfulness in wrapping blankets around the jugs to keep the coffee hot. Bless your thoughtful heart!”

—Confederate general George E. Pickett, in a letter to his wife, May 7, 1864

“I drank two cups of coffee this morning, which seem to have had an extraordinary effect upon my strength, activity, and spirits; and indeed the belief that the discontinuance of the use of this beverage, about two years ago, may have caused the diminution of all. I am, and have long been, as poor as a church mouse. But the coffee (having in it sugar and cream) cost about a dollar each cup, and cannot be indulged in hereafter more than once a week.”

—Confederate War Department clerk John Beauchamp Jones, in his diary, July 2, 1864

“Up at the first ray of light, and cooked a scanty meal of coffee and hard bread. Coffee was the main stay; without it was misery indeed.”

—Joseph Newell, 10th Massachusetts Infantry, in his diary, May 6, 1862

“A soldier’s first care, after halting, is to cook his little tin-cup of coffee, which ‘subtle poison’ is considered as indispensable to him as the air he breathes. A cup of strong, black coffee, minus milk, and oftimes made of the muddiest ditch water, will do more towards recuperating and cheering a tired, travel-worn soldier than a person who never tried it can imagine.”

—Edwin Houghton, 17th Maine Infantry, in his memoirs

“How much I miss the good coffee I used to get at home. I would cheerfully pay one dollar for as much like it as I could drink….”

—Texas soldier A.N. Erskine, in a letter to his wife, July 20, 1862

“I have a large cup that holds nearly 2 qts. I now can manage that full 2 times a day and sometimes 3 of them a day.”

—Union soldier Isaac Jackson, on the amount of coffee he was drinking while away at war, in a letter to his brother, October 21, 1862

“What is that faint aroma which steals about on the night air? Is it a celestial breeze? No! it is the mist of the coffee-boiler. Do you not hear the tumult of the tumbling water? Poor man! You have eaten, and now other joys press upon you. Drink! drink more! Near the bottom it is sweeter. Providence hath now joined together for you the bitter and the sweet—there is sugar in that cup!” —Carlton McCarthy, a member of the Richmond Howitzers, in his memoirs

Sources

The Diary of a Line Officer (1906); Hardtack and Coffee (1888); Life and Letters of Wilder Dwight (1891); Reminiscences of the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865 (1897); Marching Through Georgia (1884); Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861–1865 (1882); A Little Fifer’s War Diary (1910); A Soldier’s Story of the Siege of Vicksburg (1885); Diary of Capt. Henry C. Dickinson, C.S.A. (1910); Phil Koempel’s Diary, 1861–1865 (1923); My Diary of Rambles with the 25th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (1884); Richmond During the War (1867); Observations of an Illinois Boy in Battle, Camp and Prisons (1910); The Color-Guard (1864); Letters from the Forty-fourth Regiment M.V.M. (1863); Letters Written During the Civil War, 1861–1865 (1898); Downing’s Civil War Diary(1916); The Colonel’s Diary (1922); From Bull Run to Appomattox (1908); Four Years with the Army of the Potomac (1889); Reminiscences of a Mississippian in Peace and War (1901); The Last Campaign (1908); The Heart of a Soldier (1913); A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital (1866); “Ours” (1875); The Campaigns of the Seventeenth Maine (1866); Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb (1943); Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861–1865 (1882).

Related topics: food and drink