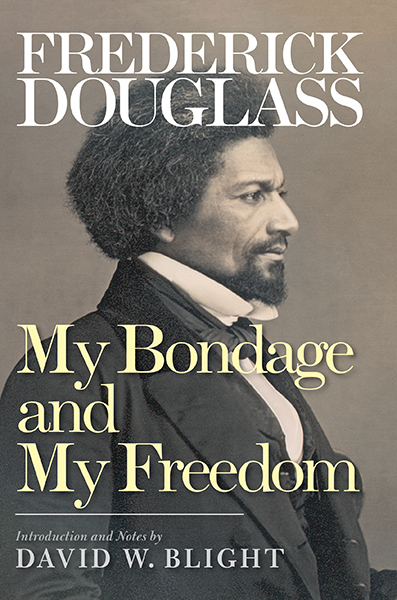

My Bondage and My Freedom by Frederick Douglass and edited by David W. Blight. Yale University Press, 2014. Paper, ISBN: 030019059X. $13.00.

The public domain is a rich and growing trove for any budding historian. Yesterday, the tomes and volumes written by the actors of the past needed to be unearthed from dusty libraries like diamonds hidden in the rough. Increasingly, those same tomes are as far away as a few words in a search box.

The public domain is a rich and growing trove for any budding historian. Yesterday, the tomes and volumes written by the actors of the past needed to be unearthed from dusty libraries like diamonds hidden in the rough. Increasingly, those same tomes are as far away as a few words in a search box.

Clicking the mouse and typing in the words “My Bondage and My Freedom” automatically unearths countless ways to read the autobiography that Frederick Douglass penned in 1855. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Documenting the American South project offers up the former slave’s text in glowing HTML. Google Books’ search function turns up another (this time in the book’s original typeset context) straight from the shelves of Stanford’s library; a similar search of the Internet Archive yields nearly a dozen scanned copies from collections around the world. Project Gutenberg offers up the book not only in plain text, but Kindle-ready for a plane ride from Maryland to New England – covering in a few hours the trek Douglass took years to formulate.

In short, any work in the public domain, and particularly one by such a universally renowned figure as Frederick Douglass, is far from rare. My Bondage and My Freedom is available anywhere, anytime. Which begs the question: why is a new print version of this book necessary? David Blight definitively answers that question with this beautiful new edition from Yale University Press.

Channeling Douglass’ ear for rich and deeply moving language, Blight’s introduction crafts a short and succinct image of the former slave, placing the work in new and stunning context. Blight has a way of using metaphor that throws striking clarity on his subject. The image he conjures of a deeply conflicted Douglass, balancing personal and political struggles, is vivid and powerful.

Blight never loses sight of Douglass’ intent in writing My Bondage and My Freedom, constantly aware that the fugitive-turned-activist was writing for public consumption in a literary style. Douglass, Blight observes, is as much an idealized character in his own narrative as he is an historical subject. And it is just this sort of observation that helps to justify a new edition of the book for the twenty-first century.

This inexpensively priced new edition may prove particularly useful in undergraduate classrooms, where study is swiftly moving away from master texts and toward source-based investigations of the past. Blight is able to act as a surrogate guide to Douglass’ world, both through his introduction and in the body of the book. Peppered liberally throughout Douglass’ original text are Blight’s observations and references. Reading this edition is like reading Professor Blight’s personal reading copy of the book, plucked from his office shelf. Countless times, for example, Blight points out small and large chunks of text that Douglass lifted from his 1845 autobiography, A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave.

But Blight’s observations go well beyond the clerical. One note delves into Douglass’ fascination with Psalm 137. Noting how a particular phrase echoes the Biblical hallmark, Blight adds that a few years earlier, Douglass quoted liberally from the Psalm in his famed Fourth of July speech. Just a handful of pages later, Blight holds a private sidebar with the reader, asking us to question Douglass’ truthfulness. “This is Douglass the master storyteller in control of his tale,” Blight observes. “A fight of two hours? Very doubtful.” In questioning Douglass’ narrative, he offers an example of how a historian must weigh his subject’s motives and honesty; the Yale professor shows us how history is crafted (197).

While perhaps not as fruitful of an experience as participating in one of Blight’s New Haven seminars, this new edition of My Bondage and My Freedom is a valuable teaching tool. Blight’s ample notes and observations will offer imaginative professors innumerable ways to discuss with students how we read texts, what we can observe as historians, and when we should doubt the people of the past.

Another reprint edition of My Bondage and My Freedom was perhaps unnecessary in an age when out-of-print books are easily sent from coast to coast via the magic of the Internet. But then again, this edition is not simply a reprint. It is a veritable guidebook to Douglass’ mind. Through his notes and observations, Blight gives the casual reader, the dedicated student, and even the wizened historian a glimpse into the mind of slavery’s most famous escapee.

John Rudy is a National Park Service Ranger working with the Interpretive Development Program in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.