A statue of Robert E. Lee sits atop the Virginia Monument on the Gettysburg Battlefield.

The Confederate monument controversy that has exploded in recent months raises fundamental questions about the American Iliad. The removal of Robert E. Lee’s statue in Charlottesville, Virginia, is only the best known of several examples that place these questions before us.

By way of offering a response, let me begin by reminding the reader that my maiden column for this series argued that “the Civil War routinely functions, in important part, as a national myth that is central to our understanding of ourselves as Americans. And like the classic mythologies of old, it contains timeless wisdom of what it means to be a human being. Homer’s Iliad tells us much about war, but it also tells us much about life. The American Iliad does the same thing.”

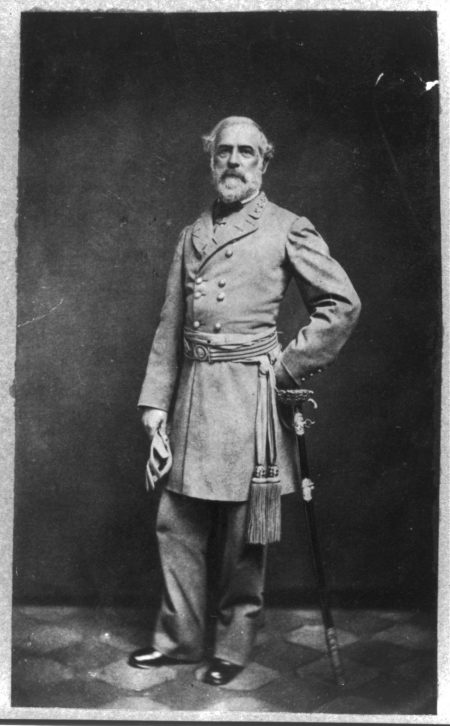

To illustrate this, I pointed to Robert E. Lee’s grace in defeat. And in a book I wrote some years ago I underscored the mythic value of Lee’s example. “Sooner or later,” I observed, “everyone loses. The dreams of youth are left behind, the promising career falters, the fatal diagnosis is pronounced. The idea of facing inevitable defeat with courage, dignity, and humanity—as Lee is rightly said to have done—therefore has powerful attraction.”

This has been very much the case for me. I am now 58 years old. At age 26 I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder—a problem with the brain’s biochemistry once called manic depression—and for more than three decades now my life has been characterized by a perpetual cycle of moving forward, being flattened by depression, and having to pick myself up to move forward again, all in the face of certain knowledge that this pattern will never end. It isn’t as bad as “inevitable defeat,” at least not in any final sense. But it is bad enough, and occasionally made worse by the stigma still attached to mental illness. To persevere in these or similar circumstances, most of us need sources of inspiration. For me, one of the most meaningful has been Robert E. Lee: his stoicism, his realism, and his willingness to play a difficult hand with courage and guts.

So let me make the obvious confession. Robert E. Lee is one of my personal heroes.

General Robert E. Lee

But let me also make an observation. The real Lee is not necessarily my hero. It would be more accurate to say that my hero is the image of Lee as I encountered it in Hodding Carter’s Robert E. Lee and the Road of Honor (1951) at age eight; in Bruce Catton’s A Stillness at Appomattox (1954) at age 12; at the Virginia Monument during my first trip to Gettysburg at age 13; and many times in Douglas Southall Freeman’s unforgettable portrait of the man in R.E. Lee: A Biography (1934–1935), which I read for the first time at age 14.

And finally, let me make a declaration. Notwithstanding the above, I am firmly of the opinion that every statue of Lee in the country, unless it is strongly contextualized, needs to be removed from public spaces. The wonderful statue of Lee atop Gettysburg’s Virginia Monument can stay. But the even more wonderful statue of Lee on Richmond’s Monument Avenue (which Freeman saluted every time he passed it) must go. I’m not happy to have reached this conclusion. But I am convinced that to do anything else risks a much greater loss.

Those opposed to removing Confederate statues often complain that it represents the erasure of history. That is patently incorrect. We are not talking about the burning of Confederate biographies or some Orwellian rewriting of history—and that isn’t what critics really mean. What they really mean is the erasure of the American Iliad, of a mythic retelling of the Civil War that for many Americans has the same cherished importance as it does for me. But let us be clear. In its present form, the American Iliad is really the white man’s Iliad, grounded in the conviction that white southerners and white northerners, similar in so many ways, tragically fought for different but morally equivalent visions of the American republic. Or, as British military observer Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle describes the two opposing sides in the movie Gettysburg (1993), one of the best cinematic expressions of the American Iliad: “The same God. Same language. Same culture and history. The same songs, stories, legends, myths. But different dreams.”

This interpretation of the Civil War did not emerge by accident. It was an important, perhaps even necessary, element in the rapid sectional reconciliation between North and South. It helped to bury the deepest resentments fast enough for the United States to move into the 20th century largely free from the internal dissension that might otherwise have hobbled its ability to achieve great power status. But it came at the expense of African Americans, for it made invisible the contribution of black troops and devalued emancipation to the point where the destruction of slavery was almost a happy side effect of the war’s outcome.

The political utility of such an interpretation has long since passed. And therefore, so has the moral utility of a national myth that is, whether we like it or not, a celebration of whiteness. If we insist that this attribute is fundamental to the American Iliad—which is the implication of the cries against the removal of Confederate monuments from public spaces—then the American Iliad is a mythic remembrance the country can no longer afford.

But unlike Homer’s Iliad, the American Iliad remains open to revision. We can change it, enlarge it, and, most importantly, set forth more forcefully its central theme: the Civil War as a struggle for human freedom. This would give emancipation the central place in our mythic understanding of the war that for decades now it has occupied in our scholarly understanding of the war.

Glory, director Edward Zwick’s 1989 cinematic masterpiece about one of the first black regiments, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, offers proof that this transformation is already underway. I have never heard a white southerner say a bad word about Glory. Indeed, hundreds of Confederate reenactors donated their time and energy as extras during its filming. (Instructively, given the way the American Iliad has excluded blacks, Zwick’s difficulty was in finding enough African-American reenactors, most of whom had to be recruited, uniformed, and equipped specifically for the film.) I do not know precisely what a revitalized American Iliad—one that speaks to all Americans—would look like. But surely it would yield a national myth more profound as well as more useful.

This should not involve the demonization of Confederate heroes such as Lee. It is needless and counterproductive to repackage Lee as a traitor, racist, and slaveholder, and it smacks of an off-putting moral sanctimony. Most of us are not just flawed but profoundly flawed (something the classic myths have always acknowledged). So why then do I regard it as imperative to remove statues of Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and other Confederates from public spaces? First, because many of those statues were erected less with the aim of honoring such figures than with co-opting their valor to make them deliberate expressions of white supremacy. But more importantly, because it is a matter of civility. As the father of a six-year-old daughter, I have grappled with the task of explaining that Lee fought to defend a republic created to perpetuate the enslavement of fellow Americans. How much more difficult is it for African-American parents, strolling through a park with their own children, who are called upon to explain the meaning of a splendid equestrian statue of someone obviously portrayed as a hero, planted in an apparent place of honor?

Assuredly, I will experience the disappearance of these statues as a personal loss. But how I feel about them is beside the point. As a citizen of this great nation I have a responsibility to understand what the statues evoke in the hearts of millions of my fellow citizens. And as for my personal investment in Lee’s example, the general himself offers the best counsel. In his postwar years Lee gave good advice to the mother of a newborn son: “Teach him he must deny himself.” That is a lesson every admirer of Lee should learn.

Mark Grimsley, a history professor at The Ohio State University, is the author of several books, including And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May–June 1864 (2002) and The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern Civilians, 1861–1865 (1995). He has also written more than 50 articles and essays.