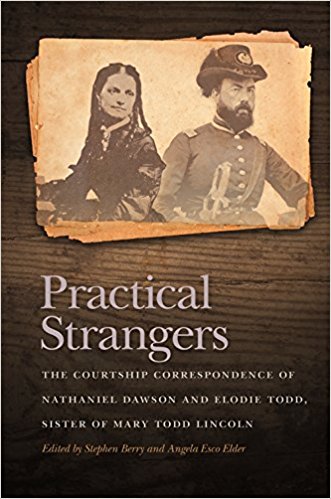

Practical Strangers: The Courtship Correspondence of Nathaniel Dawson and Elodie Todd, Sister of Mary Todd Lincoln edited by Stephen Berry and Angela Esco Elder. University of Georgia Press, 2017. Paper, ISBN: 978-0820351025. $32.95.

Even in the overcrowded field of Civil War material, Practical Strangers: The Courtship Correspondence of Nathaniel Dawson and Elodie Todd, Sister of Mary Todd Lincoln deserves attention. This collection of some 300 letters is unique because it is a lettristic conversation between two newly engaged southerners: Kentucky-born Elodie Todd, visiting her sister in Selma, Alabama, when the war begins, and Nathaniel Dawson, serving as an officer in the Fourth Alabama regiment, stationed in Virginia. For the most part Civil War correspondence is a one-way affair, usually in letters sent from the battlefront and carefully cherished by those at home. In this case, though Elodie wanted her letters destroyed, Nathaniel Dawson sends them back to her and persuades her to keep them, as she kept his, so that he could read them after the war in the loving family circle they will create after their marriage. Thus, readers are privy to an intimate conversation that takes place from April 1861 to April 1862, with the letters serving as proxies for two lovers deepening their relationship.

Even in the overcrowded field of Civil War material, Practical Strangers: The Courtship Correspondence of Nathaniel Dawson and Elodie Todd, Sister of Mary Todd Lincoln deserves attention. This collection of some 300 letters is unique because it is a lettristic conversation between two newly engaged southerners: Kentucky-born Elodie Todd, visiting her sister in Selma, Alabama, when the war begins, and Nathaniel Dawson, serving as an officer in the Fourth Alabama regiment, stationed in Virginia. For the most part Civil War correspondence is a one-way affair, usually in letters sent from the battlefront and carefully cherished by those at home. In this case, though Elodie wanted her letters destroyed, Nathaniel Dawson sends them back to her and persuades her to keep them, as she kept his, so that he could read them after the war in the loving family circle they will create after their marriage. Thus, readers are privy to an intimate conversation that takes place from April 1861 to April 1862, with the letters serving as proxies for two lovers deepening their relationship.

Divided into two sections, “To War” and “To the Altar,” with maps of Selma and Bull Run (as well as lists of the fifteen children of Robert Todd, who make frequent appearances in Elodie’s letters), Practical Strangers is lightly edited. It is especially strong on the identification of persons mentioned in the letters, but is weaker on contextual strategic information about the movements of Nathaniel’s regiment and events such as the sinking of the Pensacola. Surely the translation of “entre nous” is less deserving of mention than material on developments in Kentucky, a constant worry for Elodie, or identification of Hardee’s book on tactics or editorial material on the treatment of Elodie’s sister, Margaret Todd Kellogg, in Cincinnnati. But these are quibbles about a carefully transcribed series of letters that presents a fascinating primary source illuminating several aspects of the Civil War.

The letters between Elodie and Nathaniel tell us much about courtship in the South. Nathaniel has just proposed to Elodie before he leaves Selma to fight for the Confederacy. Eleven years older than his fiancée, his letters evoke his sentimental hopes for the household they will establish when they marry after his one-year military service ends. In the flowery language of a besotted lover, he writes that she has the winning combination of modesty and cultivation. With a lock of her hair in his locket, he intends to protect her as he presses for a marriage that she, for the moment, deflects. Indeed, he conflates his romance into a reason for his military service: “Am I not fighting for you?” and then, in the classic southern connection to medieval times and Sir Walter Scott’s novels, “Am I not your sworn knight and soldier?” (21).

Elodie responds with affection but also warns that she is a Todd, a family well known for its tempers. She never mentions his first two marriages—his second wife has been dead less than a year—or the fact that after her marriage, she will become the stepmother of his two young children. (Faced with a widowed father who was courting her, Elodie’s famous half-sister Mary Todd noted her suitor’s “two sweet objections.”) At first Elodie is reticent—a characteristic typical of young women who hesitate before marriage, having much to lose—even as Nathaniel encourages her to write with frankness. But in time, reacting to his persistent assertion of his love (and perhaps his insistence that there can be no happiness if a wife has no influence over her husband), her commitment intensifies. She signs her letters “Dee”; she moves from affectionate to “I am as ever yours” (166). And their love sealed by their letters, the two marry in Selma shortly after Nathaniel completes his service to the Confederacy.

These were the months of all quiet along the Potomac, and Practical Strangers illuminates the hardships of camp life that became especially intolerable during the winter—the bad food, the disease that kills several members of Nathaniel’s company, the fights among soldiers, the marches and anticipated battles. Nathaniel, who is accompanied by one of the enslaved who worked on his plantation, did fight at the Battle of Bull Run, but some considered his actions cowardly after he sprained his ankle and was accused of leaving the battlefield.

Meanwhile, Elodie’s letters from Selma describe life on the homefront in the early days of the Confederacy, when white women organized tableaux, sewed and knitted—in this case, so many hats and socks that Nathaniel informs her his company is oversupplied. Elodie visits friends; sings as a solo the Marsellaise at fundraising events; reads Motley’s Rise of the Dutch, with its lessons for the Confederacy; and spends time writing 1500-word letters to Nathaniel. In these letters, she displays political understandings unusual for even elite women. She decries the neutrality of her home state of Kentucky and worries about her brothers, especially the baby Alec, who later dies in a friendly fire incident at Baton Rouge. Given her strong sense of family loyalty she will not permit criticism of her brother-in-law Abraham Lincoln in public, but in private, she complains of his tyrannical policies.

Finally, these letters display the optimism of the Confederacy in its early days. It is clear to both Elodie and Nathaniel that they are fighting the “Black Republicans” led by “King Lincoln,” that the North will not have the resources to subdue the South and, according to Nathaniel, that the Confederate army will be in Washington by Christmas. These predictions did not come true; what did was the abiding, mutual affection of Elodie Todd and Nathaniel Dawson.

Jean Harvey Baker is the Bennett-Harwood Professor of History at Goucher College and the author of Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography.