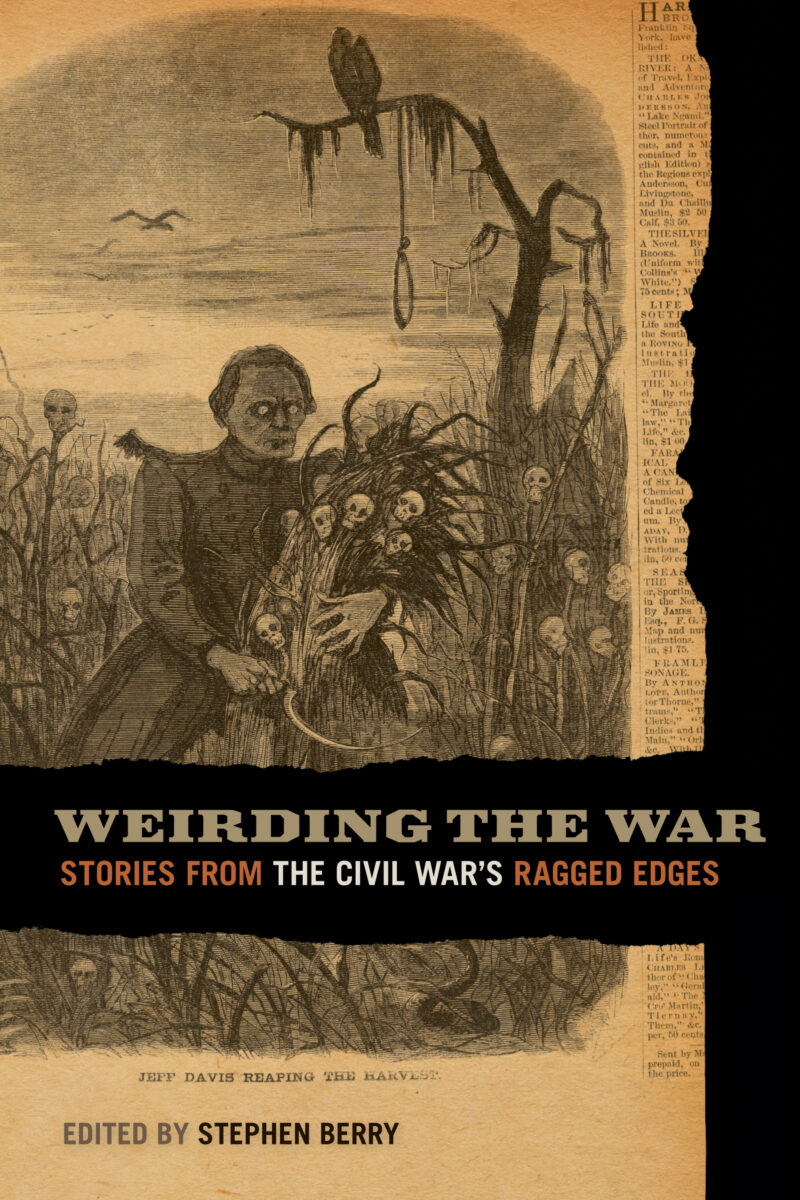

What we have here is an excellent collection with a terrible title. (I confess I am a curmudgeon about titles. It is time to stop torturing nouns by turning them into verbs. I also long for the day when gerunds are not used in book titles.) The title implies more and less than the collection delivers. Many of the essays are solid scholarly contributions that could have been published in any number of journals or places during the past quarter century. Labeling such contributions “weird” does not make them “weird.” Rather it speaks to the contributors’ ambition to free themselves from the heavy hand of convention that weighs on the field of Civil War history. Stephen Berry, the editor, is at pains to separate this collection from the mythic rendering of the Civil War that still grips the imaginations of countless Americans. But the self-conscious positioning seems overdone and overly self-important. The good news is that the scholarship on the Civil War era is livelier and more interesting than at any time in the past half century. There really isn’t a need to “weird” the Civil War. What is needed is a translation of the new scholarship into a form that the vast lay audience of Civil War enthusiasts will consume. And it is in this regard that the title (and this collection) falls short. A few of the essays play with language and the essay structure, but most comply with the conventions of academic scholarship. Not only is their subject matter less “weird” than the title might suggest, their form is entirely familiar. So I’ll assume the title is at once a marketing ploy and a playful trope and I’ll leave it at that.

The essays themselves explore nooks and crevices of Civil War history that are always interesting, sometimes poignant, and often revelatory. Berry’s introduction is especially cogent about the thread that runs through the collection: the “littleness” of the war. Almost certainly this view of the conflict is rooted in the experience of contemporary Americans with war. We have a half century of experience with the littleness of war. The avoidance of grand narrative tropes in the collection also reflects the popularity of “micro-narratives” that allow scholars to tell stories, replete with thick description, but to avoid the flattening and simplification that often detracted from the history produced by scholars of yore.

Some of the essays are suggestive and should inspire historians to pursue the subjects in question further. Rodney Steward, for example, compiles compelling evidence to suggest that wartime confiscation laws enabled obscure Confederate bureaucrats, specifically in North Carolina, to enrich themselves. One is left to wonder how many postwar fortunes in the South had their origins in similar corruption. Barton Myers revisits the torture of a Unionist wife in North Carolina to speculate about the catalysts for wartime atrocities. Other essays are playful and inventive. Berry’s own essay on mining coroners’ reports is a tour de force, written with élan. It is both a reflection on the tragic effects of the war and their continuing fascination for us. Daniel Sutherland’s counterfactual essay traces artist James Abbott Whistler’s career as a Confederate officer, a career that he never had. The value of this exercise is that is underscores the contingencies in Whistler’s life that might have broken very differently, while simultaneously enabling Sutherland to explore, in an highly entertaining manner, Whistler’s ties to the Confederate South. Some essays take a familiar topic and recast it in a provocative manner. Joan Cashin’s essay lingers on hunger in the Confederacy. Rather than dwell on the familiar story of the bread riots of 1863, Cashin delves into the broader implications of hunger within the Confederacy and during the immediate postwar years. In her telling, we see glimpses of the privations inherent in all wars. Finally, some essays, like Leslie Gordon’s, are poignant miniatures whose larger meanings are ambiguous. Gordon recounts the heartrending story of a Union veteran who sinks into apparent insanity and is eventually institutionalized by his former comrades. This saga prompts us to reflect on the long shadow the war cast over the lives of the Civil War generation.

Taken as a whole, this collection implies that most of the “weird” Civil War took place in the South and involved southerners. Southerners may be prone to an abnormally lengthy list of pathologies, but the southern accent here left me wondering whether the definition of “weird” upon which this collection rests might not impose its own limits. I’m all in favor of a picaresque history of the Civil War. But if we are to limn the “littleness” of the Civil War and expose the full extent of the venality unleashed by the war the net will have to be cast wider. But let there be no mistake; this collection deserves (and repays) careful reading. My hat’s off to the editor and contributors. (Did I mention I still don’t like the title?)

W. Fitzhugh Brundage is the William B. Umstead Professor of History at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.