Major General Benjamin F. Butler

What if? This is the eternal question that so often confounds students of Civil War military history, and leads to groundless flights of fancy (or fantasy) as often as to any deeper understanding of the past. Still, the what ifs of the conflict—What if Great Britain had intervened? What if the Confederates had won at Gettysburg? What if Lincoln had not been assassinated?—still preoccupy us because they point to what might have been, what need not have been, and perhaps most interesting, how human decisions shaped historical outcomes.

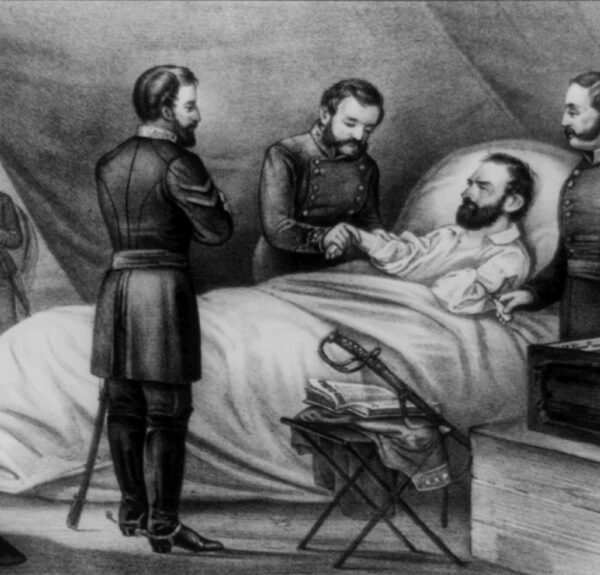

Often our hypotheticals and analyses take place on battlefields, and there is no doubt that war is an excellent motif in which to test the power of decisions and their outcomes. However, I would like to examine another, less celebrated moment of decision that had profound implications for what followed, one that represents a crucial moment in the history of slavery’s demise: Major General Benjamin F. Butler’s decision to implement military emancipation in 1862.

In May 1861, Butler commanded Union forces at Fort Monroe in Virginia. Before the war Butler, a Massachusetts Democrat, had been a trial lawyer and owed his position in the army to political connections, including to allies in the Lincoln administration. Which is to say Butler was a savvy political operator who understood the touchy issues at play early in the war. Faced that summer with a wave of runaway slaves who escaped through Union lines, Butler decided to go beyond his mandate and engage in military emancipation. He probably didn’t view the runaways as anything more than a problem that needed solving, but as a lawyer, he certainly understood how Confederates saw the runaways—as chattel and military assets.

Butler figured that if he could somehow deprive the enemy of the use of these human assets, he would not only undermine Confederate forces in the region, but he could also defend the decision as consistent with the principal Union aim of dismantling the Confederacy’s war-making ability. The problem was that the Lincoln administration had not granted him any emancipatory permission. Butler refused to let this stop him, and so made a momentous decision: He designated the Fort Monroe runaways as “contraband,” and thus subject to confiscation under his authority as a United States Army officer. Since the Confederates considered slaves to be property, Butler reasoned, then he would oblige them, and treat them as property to be taken under the rules of war.

Lincoln’s advisers were, to say the least, dismayed. Without Butler realizing it, his decision forced Lincoln to confront the question of emancipation before he had thought it necessary to do so. Facing this dilemma, Lincoln could either accept Butler’s act and support the policy, or face the unacceptable alternative of returning the runaways to slavery. With little wiggle room, Lincoln decided to let Butler’s acts stand. Later, the policy was manifested in law as the First Confiscation Act.

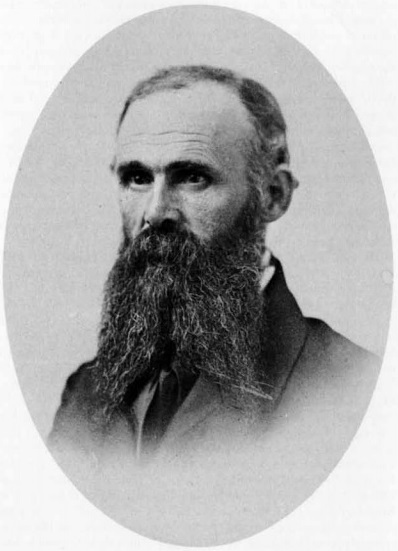

John W. Phelps

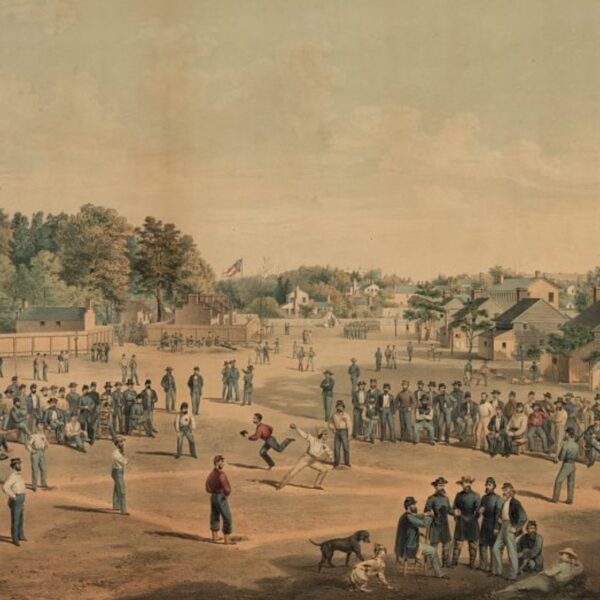

Butler’s intervention was not finished though. The next year, in the spring of 1862, he took over command of occupied New Orleans. One of Butler’s subordinates was the Vermont abolitionist and West Pointer Brigadier General John W. Phelps. When a wave of runaway slaves arrived, as had happened at Fort Monroe, Phelps wanted not only to implement emancipation but also to enlist such freed slaves into the Union army; he saw confiscation for what it was, a legal maneuver that was largely semantic in nature. He began encouraging enslaved people in the area to escape and take refuge with the Union army. After all, Phelps reasoned, slavery was “a universally recognized social and moral evil”; he declared slaves “ripe for manumission, and any measure to avert it may put off, but cannot long prevent, a revolution—a revolution of that kind where men are restored to their original rights.”[1]

Butler had had a change of heart after his Fort Monroe experience, and feared that Phelps’ invitation would overwhelm the army’s ability to support the runaways. Butler tried and failed to rein in Phelps, and they quickly had a falling out. “I shall have trouble with Phelps,” Butler fumed to his wife that summer. “He is mad as a March Hare on the ‘nigger question.’ He is arming them against the law and refuses to have them work. My respect for him will lead me to treat him very tenderly but firmly, and I hope involve myself no more than is absolutely necessary for my duty.”[2] Phelps had, to Butler’s chagrin, allowed runaways to “range the countryside, insult the Planters and entice negroes away from their plantations,” all of which contributed to a general climate of lawlessness and disorder.[3]

At first, Butler attempted to re-create his Fort Monroe confiscation policy. The result was a flood of more runaways, encouraged by Phelps. By mid-June 1862, nearly 300 fugitive contrabands had swamped the Union facilities, and by November, that number had swelled throughout the region to, in Butler’s estimate, “ten thousand negroes to feed … principally women & children.”[4]

Phelps had given Butler a taste of his own medicine, making decisions that forced Butler’s hand in much the same way that Butler had forced Lincoln’s. When Butler complained to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, Chase sympathized: “It is quite plain that you do not find it so easy to deal with the contraband question [in New Orleans] as at Fortress Monroe.” Chase made it clear that the president would remain noncommittal for the moment. “Of course until the Government shall adopt a settled policy,” Chase said, “the commanding General will be greatly embarrassed by it.” Butler would not be able to move the timetable, and Chase could only promise him that a decision would come “soon,” and though the president’s “mind is not finally decided,” his language “points to a contingency in which he may recognize the same necessity.”[5]

The situation resolved by the end of the year. Phelps, who had overplayed his hand, eventually resigned under pressure, but the bell had been rung. Butler realized he would not be able to stem the tide of runaways to Union lines and, over time, came around to the idea of raising regiments of black troops.

Without intently meaning to, Butler, along with other, more abolitionist-leaning Union officers, made decisions that nudged the broader national emancipation policy toward reality in January 1863. Furthermore, Butler’s decisions in Virginia and Louisiana encouraged thousands of enslaved African Americans to free themselves in 1861–1862 on an unprecedented scale. Had he not engaged in confiscation or emancipation, these acts of agency might not have happened in the same way—or at all. This can tell us something about the nature of decisions: They set others in motion, sometimes in unexpected ways that can have profound ripple effects on the political and strategic consequences that follow. Union military confiscation and emancipation policies also influenced the Lincoln administration’s development of its war aims, its timing of the Emancipation Proclamation, and, ultimately, the very nature and purpose of the Civil War.

Far from being inevitable or predetermined, emancipation unfolded in an uncertain, nonlinear progression of interconnected actions and choices, subject to politics, personality, law, custom, and chance. What if Butler had not tried to emancipate slaves in Virginia and New Orleans? Would Lincoln’s emancipation policies have unfolded in the same way historically, or would the timing and outcome have looked very different?

ANDREW S. BLEDSOE IS ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AT LEE UNIVERSITY IN CLEVELAND, TENNESSEE. HE IS THE AUTHOR OF CITIZEN-OFFICERS: THE UNION AND CONFEDERATE VOLUNTEER JUNIOR OFFICER CORPS IN THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR(LSU PRESS, 2015); THE CO-EDITOR, WITH ANDREW F. LANG, OF UPON THE FIELD OF BATTLE: ESSAYS ON THE MILITARY HISTORY OF AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR(LSU PRESS, 2019); AND AUTHOR OF THE FORTHCOMING DECISIONS AT FRANKLIN: THE NINETEEN CRITICAL DECISIONS THAT DEFINED THE BATTLE (UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE PRESS).

This article appeared in the Winter 2021 (Vol. 11, No. 4) issue of The Civil War Monitor.

Notes

1. Kristopher A. Teters, Practical Liberators: Union Officers in the Western Theater during the Civil War (Baton Rouge, 2018), 29.

2. Benjamin F. Butler to Sarah Hildreth Butler, April 2, 1862, Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, compiled by Jesse Ames Marshall 5 vols. (Norwood, MA, 1917), 2:154.

3. Benjamin F. Butler, quoted in Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy toward Southern Civilians, 1861–1865 (New York, 1995), 128.

4. Benjamin F. Butler to Abraham Lincoln, November 28, 1862, Private and Official Correspondence, 2:448.

5. Salmon P. Chase to Benjamin F. Butler, June 24, 1862, Private and Official Correspondence, 1:633.

Related topics: emancipation