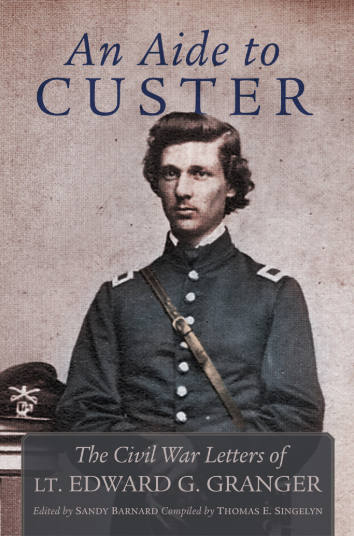

An Aide to Custer: The Civil War Letters of Lt. Edward G. Granger edited by Sandy Barnard and compiled by Thomas E. Singelyn. University of Oklahoma Press, 2018. Cloth, ISBN: 978-0806160184. $39.95.

George Armstrong Custer’s legend largely rests on his participation in the Indian Wars and his death at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876; however, as many scholars have observed, Custer’s service during the U.S. Civil War service is equally worthy of attention. How fortunate, then, that Thomas Singelyn took advantage of an offer made by of one of Lieutenant Edward Granger’s descendants to let him borrow and transcribe forty-three letters Granger wrote during the U.S. Civil War. Granger, who enlisted in the 5th Michigan Cavalry Regiment in 1862 and became one of Custer’s aides in 1863, had a great deal to say about the general. As editor Sandy Barnard contends, Granger “provides unique personal insights into his celebrated leader, General Custer. He frequently comments on Custer’s unparalleled abilities as a combat leader on the battlefield, but he also describes the general’s personal actions as a still young and single officer who enjoys hanging out with his subordinates in camp and keeping an eye on the young ladies” (xvi).

George Armstrong Custer’s legend largely rests on his participation in the Indian Wars and his death at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876; however, as many scholars have observed, Custer’s service during the U.S. Civil War service is equally worthy of attention. How fortunate, then, that Thomas Singelyn took advantage of an offer made by of one of Lieutenant Edward Granger’s descendants to let him borrow and transcribe forty-three letters Granger wrote during the U.S. Civil War. Granger, who enlisted in the 5th Michigan Cavalry Regiment in 1862 and became one of Custer’s aides in 1863, had a great deal to say about the general. As editor Sandy Barnard contends, Granger “provides unique personal insights into his celebrated leader, General Custer. He frequently comments on Custer’s unparalleled abilities as a combat leader on the battlefield, but he also describes the general’s personal actions as a still young and single officer who enjoys hanging out with his subordinates in camp and keeping an eye on the young ladies” (xvi).

Throughout the letters, Custer received much positive attention from Granger. In one letter to his sister, Granger wrote, approvingly, “Custer is one of the ‘fighting Generals’ of whom we read so much and see so little: but there is no doubt about his fighting qualities, for his command has not been in a single engagement in which he has not been under fire” (118). In addition, Granger often referenced Custer’s coolness and bravery under fire.

Granger’s letters are not interesting merely because they provide information about Custer, however. In fact, until he joined Custer’s staff, Granger had little to say about the man. Rather, his letters provide “an intimate look into a maturing young man as he meets the ever-challenging experiences of the Civil War” (xv).

Granger’s descriptions of the minutiae of army life are worth noting. For instance, speaking of two captains vying for the position of major, Granger wrote, “Capt Hunt was raving mad. He cursed the ‘political influence’ which had obtained for Dake the Majority, he was going to resign and charges would be preferred against Dake, etc. Now I believe the game is to have Dake brought up before a Board of Examiners. If this is done, he will certainly be thrown out as, like some of his brother officers, he has been so busy figuring for promotion that he knows nothing about the tactics” (47). Here, Granger provides glimpses of the legendary infighting in the Army of the Potomac; how disappointed aspirants for promotion sought to explain and avenge their defeats; and the classic complaint that some officers paid too much attention to promotion and not enough to tactics.

On another occasion, Granger complained to his mother that his clothes were falling apart: “my jacket is minus half the regulation number of buttons, there is a hole under the arm through which I get my fist, once in a while, by mistake, and now one of my shoulder straps is torn off. My pantaloons are some that I drew—regulation—and pretty shabby at that. My cap looks as if it had been in the service six years, instead of six months” (53). Many of Granger’s contemporaries complained about “shoddy aristocrats,” or industrialists who sold defective goods to the government. Perhaps Granger’s clothing came from one of these men, or perhaps it illustrated how army life tended to chew through clothing.

Interestingly, Granger disliked George Meade’s pursuit of Lee after the battle of Gettysburg and commented that the commander of the Army of the Potomac “was considered an out & out Rebel at the beginning of the war” (114). Granger would have little patience with a recent trend among historians to exonerate Meade’s performance in July and August 1863.

Granger’s relationship with his family also merits comment. Like all soldiers, he complained that he wrote more than his family members and that the folks on the homefront needed to write with greater regularity. Comments such as “I had almost given up expecting letters from anyone” (172) appeared quite often in his letters. Furthermore, he sometimes threatened to cease writing. In one instance, he told his mother that he would have answered her letter earlier “if I had not happened to feel somewhat provoked at the irregularity of my letters from home & thought I would try and see how you like the style of corresponding you practiced” (208). Furthermore, Granger continued, “if my correspondents don’t ‘come to time’ hereafter, I shall quit writing, entirely” (208). Despite impatience with his relatives, Granger’s letters to his mother and sister nevertheless demonstrated great love and affection.

Readers familiar with the letters of Civil War soldiers will see many similarities between Granger’s letters and those of other soldiers. Granger perceptively detailed his army experiences and, in so doing, provided another perspective about the U.S. Civil War. Furthermore, as a member of the 5th Michigan and an aide to Custer, Granger helps readers understand the evolution of the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry from “an amateurish collection of near circus riders who lacked a precise combat role” to “an increasingly polished force that seized the momentum from its enemy and became dominant” (3).

In sum, Singelyn and Barnard have produced a useful volume of letters that detail an officer’s perspective about military life and Custer. Custer scholars will no doubt appreciate having Granger’s impressions of the general transcribed and published, but these letters will also prove helpful to scholars who focus on U.S. Civil War and military history.

Evan C. Rothera teaches in the Department of History at Sam Houston State University.