One hundred fifty years ago today, on October 21, 1861, Union troops suffered a humiliating defeat in what would come to be known as the Battle of Ball’s Bluff. After crossing the Potomac River to conduct a reconnaissance in the vicinity of Leesburg, Virginia, a small Union force was routed by the opposing Confederates, who drove the survivors back down the steep banks of the Potomac and into the river in search of the safety of the opposite bank. By day’s end, slightly over 500 Union soldiers had been captured—unable or unwilling to swim the river under fire—and another 500 killed or wounded.

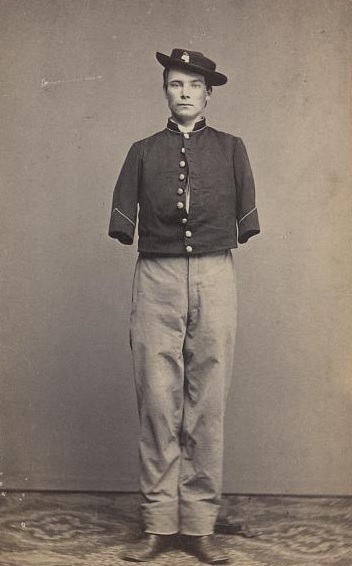

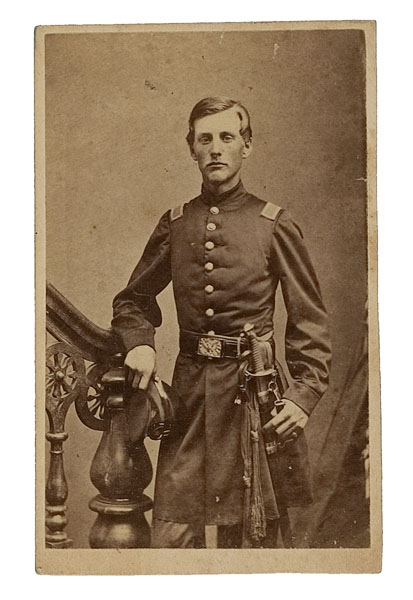

Among the Union soldiers at Ball’s Bluff was Richard Derby, a 26-year-old captain in the 15th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. In the days that followed, Derby described the battle—and his many close calls—in a series of three letters to family and friends. They are presented below, in the order Derby wrote them.

I. Poolesville, Md. October 22d, 1861.

My Dear Mother —

I hasten to send you, by the first mail, a few lines to relieve you from anxiety about my fate. We have had a terrible fight, but I have come out of it “safe and sound,” except the effects of exhaustion and fatigue.

We crossed into Virginia, and were driven back to the river, and had to swim it or be captured; of course I took to the water, but had a hard time over. Ours, Company H, had a fight all by itself before the rest of the regiments were engaged. Everybody acknowledged that we fought nobly, but, after fighting all day, we were repulsed, and I am afraid there isn’t half the regiment left.

I suppose the fight will go on to-morrow, but we shall not take part in it. They are burying the dead to-day, it being cold and rainy.

I am ever your affectionate son,

(Capt.) Richard Derby.II. Poolesville, November 2d, 1861.

[Recipient unknown.]

I HAVE received your two letters after you heard of my safety…. You will see the folly of giving much credit to newspaper reports…. Captain P —, drove me out of the tent to-day (it stormed furiously), and said I must go in-doors to recruit, after my drenching in the river. I was quite ill for several days after. I lost my sword, pistol, and belt, as did all who swam the river. I put them on a board and tried to push them across, but could not get along with one hand, and had to let them go to the fishes. I came out of it better than some who threw away clothes, money, and all. Captain Philbrick swam across with his money in his mouth. Captain Bowman was a schoolmate of mine in Groton. We are now afraid he was drowned. He could not swim, and made one attempt to cross on a small raft, but returned. Some time after, Captain Watson thought he heard his voice out in the stream crying for help, and is afraid he made another attempt and was drowned…. Miss Dix has been up from Washington, and supplied the wounded with all sorts of comforts and luxuries. They are generally getting along finely.

We are looking for great deeds from the “naval expedition.” If that succeeds, it will lighten our tasks on the Potomac; if, on the other hand, it fails, we may have trouble with England and France. I hope it is out of reach of this tremendous storm. You must not look on the dark side in regard to the war: affairs are at this time looking better for us than ever before….

Your ever affectionate

Richard.III. [No date.]

[Rev. James Means.]

The fight was pronounced by all to have been a very severe one, and the ratio of loss was greater than that of “Bull Run.” It is a mystery to me how any man escaped the shower of bullets that was poured in upon us for two hours.

The pieces of artillery seemed to be the especial target of the sharp-shooters, and hardly a man was left standing by them after the second volley. I had always been afraid that the men would become unmanageable, but I was never more disappointed. Through the whole affair, from our embarkation in the miserable little skiffs to the retreat down the bluffs, they obeyed every order as promptly as though they were merely drilling, and fought as coolly as veterans. They showed the real English “pluck,” and I think if they had no seen that it was a hopeless and desperate fight, they would have added some of the French “dash,” and carried every thing before them.

Early in the forenoon, Company H had a skirmish on its own account, with a company of Mississippi riflemen. We got the better of them, even with our old smooth-bore muskets, but had to fall back to the shelter of the woods on the approach of cavalry. Our loss was seventeen killed and wounded in that affair, and the same in the general battle. I went through the whole of it without a scratch, not even a hole in my clothes. I was very much disappointed, as some officers had three or four bullets through their coats and caps; so I made up for it by nearly drowning myself in the Potomac.

I hadn’t a suspicion but what I could swim across with ease, so I pulled off my boots, and laid my sword, pistol, and belt on a small board to push across. I was anxious to save my sword, as it looked too much like surrendering to lose that.

I kept all my clothes on, and my pockets full. I pushed off quite deliberately, although the water was full of drowning soldiers and bullets from the rebels on the top of the bluff. I made slow progress with one hand, and had to abandon my raft and cargo. I got along very well a little more than half way, when I found that every effort I made only pushed my head under water, and it suddenly flashed across me that I should drown.

I did not feel any pain or exhaustion—the sensation was exactly like being overcome with drowsiness. I swallowed water in spite of all I could do, till at last I sank unconscious. There was a small island near Harrison’s, against which the current drifted me, and aroused me enough to crawl a step or two, but not enough to know what I was doing, until I dropped just at the edge of the water with my head in the soft clay mud. My good fortune still continued, and Colonel Devens, swimming across on a log, landed right were I laid. He had me taken up and carried over to Harrison’s Island, to a good fire, where I soon began to feel quite comfortable, but was afterwards taken ill, and have been till this time recovering.

I feel as if it was in answer to the many prayers of my friends that I was saved at last through so many dangers…. Notwithstanding our mutilated condition, we are ready to “try again,” but hope they will show a little better generalship on our side.

[Lieut. Derby]

While Derby would recover from his Ball’s Bluff experience, he would not survive the war. Less than a year later, at the Battle of Antietam, a Confederate bullet pierced his temple, fatally wounding him. At the time of his death, Derby was two weeks shy of his twenty-eighth birthday.

Source: Soldiers’ Letters, from Camp, Battle-field and Prison (New York: Bunce & Huntington, 1865), 34-37. Image credit: Cowan’s Auctions (www.cowanauctions.com).