Readers of Civil War history know there’s no shortage of books on the Confederate military. The Confederate States of America was, after all, a country born at war and destroyed by war. To understand the Confederate experience one needs some grasp of the fledgling nation’s fighting forces—yet in innumerable military studies, those many thousands of men who did the fighting are mostly background to the profiles of elite officers and studies of major battles. Those works touch occasionally on elements of soldier life by default but do not mean to offer up the experiences of Johnny Reb. Even Confederate unit histories focus more on the operations of a regiment or brigade, or its reputation, than on the daily grind of marching, digging, freezing, starving, fighting, coping, dissenting, persevering, healing, and dying in terrible and painful ways.

Where did Johnny Reb come from? What motivated him? What kept him fighting when all appeared lost? What did the men do to socialize or entertain themselves in the sometimes monotonous periods between battles? What did they eat or wear or spend their money on? How did they feel about their commanders? How did they distinguish the Confederate cause from the government in Richmond? How did they imagine themselves compared with Union soldiers? And how did they understand their place as individual soldiers inside an unimaginably large military conflict?

Variations in class, geography, and social cultures within armies always exist. But taken collectively, these books put a face on Johnny Reb and so lay a foundation for understanding the men who made up the Confederate experience.

The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy

Bell Irvin Wiley (Bobbs-Merrill, 1943)

Bell Wiley’s The Life of Johnny Reb has been reprinted several times since 1943—for good reason. Rooted in letters and diaries penned during the war, this is the original social history of the Confederate soldier and the one that all subsequent historians attempt to update or supplant. (Wiley’s 1953 The Life of Billy Yank provided a mirror for Union soldiers.) Writing well before the New Social History exploded in the 1960s and without the benefits of digital technology available to historians today, Wiley touches on everything from procuring food, camp life, and the fighting spirit to the emotional struggles of men dealing with cowardice or homesickness (or both). As the preface to an edition from the late 1970s makes clear, Wiley admired the character of rank-and-file Confederates—he contends they relished being rebels—and sought to rescue them from their oafish depictions in popular culture. This view of average Confederate soldiers motivated Wiley to thoughtfully explore their lives; it also led him to sidestep issues of race, something a more modern historian could not have done without immediate criticism.

Co. Aytch

Samuel R. Watkins (Times Printing Company, 1900)

In the wake of the war, a public consumed with controlling the conflict’s historical legacy couldn’t get enough of soldiers’ memoirs. Between the 1870s and 1920s, firsthand accounts of army life became an industry. Today, the great majority of accounts written by enlisted men are unknown outside of local history circles or roundtables. The recollections of Sam Watkins, a Confederate soldier from Maury County, Tennessee, are a notable exception; this might be the most famous Civil War memoir not written by a former general or president.

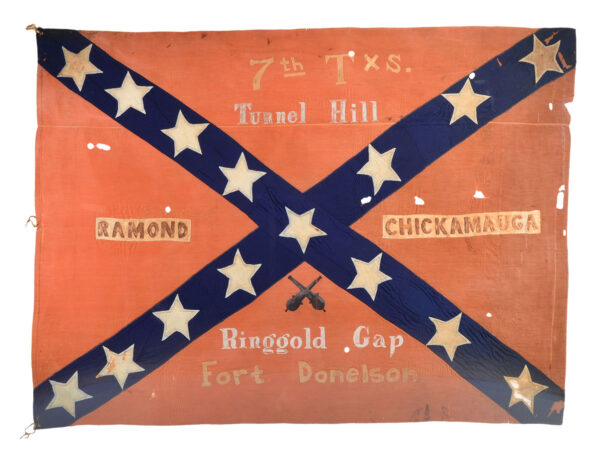

As with all firsthand accounts, and especially ones recorded 20 years after the fact, readers should take Watkins’ memories, in his folksy dialect, with a grain of salt. Even well-intended memoirists have agendas— historical, commemorative, or otherwise—and target audiences. With all that in mind, Watkins provides great insights into how men entertained themselves in camp, dealt daily with the weather, and fed themselves when provisions were short. Most interesting are his narratives of the bloodlettings at Shiloh and Chickamauga. So often battle histories are told from a bird’s-eye view, with an omniscient quality that erases the fog of war. But “Co. Aytch” tells of these engagements from the perspective of an individual soldier in real time—which is to say, by a man who experienced great physical and emotional trauma but was little aware of what was happening elsewhere on the line, let alone on the battlefield.

Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served Under Robert E. Lee

Joseph T. Glatthaar (University of North Carolina Press, 2011)

What many readers don’t realize about their favorite histories of the Civil War is just how much material wound up being cut. Joseph Glatthaar’s Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia—a companion piece to his General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse (The Free Press, 2008)—is unique on this list because it shows us virtually everything that would have been considered excess. Glatthaar surveyed census data for 600 soldiers from Robert E. Lee’s army and sorted it into more than 50 analytical categories including (but not limited

to) wealth, age, class, marriage status, property ownership, and connections to slavery. From the patterns that emerge in the form of charts and graphs and sequences, Glatthaar makes instructive arguments about trends in enlistment and desertion, the representation of slaveowners in the Army of Northern Virginia, and the adage that it was a “rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight.” Based on his sampling from Lee’s army, Glatthaar pushes back against this last notion and reveals just how ingrained the institution of slavery was in the Confederate rank and file.

Diehard Rebels: The Confederate Culture of Invincibility

Jason Phillips (University of Georgia Press, 2007)

Jason Phillips’ Diehard Rebels has the narrowest focus among these books but it also attempts to answer perhaps the trickiest question: Why did so many Johnny Rebs keep marching, following orders, fighting, and most importantly, believing they could win the war long after it became apparent their cause was doomed? Mining letters and diaries from “diehard Rebels” who served in all theaters of the war, Phillips blueprints an ethos or culture of invincibility that existed among a select demographic of Confederate ultras. The belief that God would not allow the Confederacy to lose, hate-fueled perceptions of Yankee invaders, and misinformation (read: rumor and gossip) about the actual state of their war effort were necessary elements to the culture. Given the nature of his study, it’s difficult for Phillips to precisely identify and quantify diehard Rebels, which may seem odd given the other social histories here. That said, he approaches the study of Confederate fighting men and their values and motivations without hindsight—because soldiers didn’t have it in 1864–1865. Phillips illuminates a simple but critical point about understanding Rebel soldiers: What enlisted men thought was true during the war, not what we know today, spurred their actions.

Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee: A Portrait of Life in a Confederate Army

Larry J. Daniel (University of North Carolina Press, 1991)

While Bell Wiley’s The Life of Johnny Reb skews toward men who served in the East, Larry Daniel’s landmark Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee offers the same level of detailed coverage but for the troops of a western unit. Daniel focuses on what soldiers in the famous army (commanded in turn by Braxton Bragg, Joseph E. Johnston, and John Bell Hood) ate, how their operations were affected by disease, how they coped with the loss of comrades, and how they practiced their religion in the middle of a war. Daniel also attends to literacy, morale, and discipline as he creates his composite Johnny Reb in the western theater. Relying on wartime letters and diaries and avoiding postwar memoirs, Daniel argues that noteworthy cultural and practical differences set Confederates in different geographic theaters apart—and he pioneers the notion of prioritizing the western perspective. This is a well-illustrated book that, like The Life of Johnny Reb before it, underscores the necessity of “bottom up” history to fully understand the experiences of everyday fighting men. Like Wiley, Daniel somewhat avoids issues of race and slavery that undoubtedly influenced men in the Army of Tennessee, whether or not they owned slaves.

Matthew Christopher Hulbert is Elliott Associate Professor of History at Hampden-Sydney College. He is the author or editor of five books, the most recent being the biography Oracle of Lost Causes: John Newman Edwards and His Never-Ending Civil War (Bison, 2023), which was a 2024 Spur Award finalist.

Related topics: Confederacy