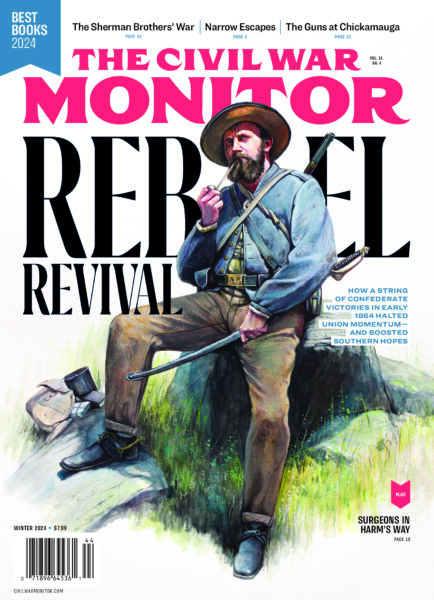

REBEL REVIVAL

William Marvel’s statement in his recent article [“Rebel Revival,” Vol. 14, No. 4], “The disproportionate number of killed among Colored Troops implied an inclination to refuse quarter” at Fort Pillow, is like saying that the crashing of two planes into the Twin Towers implied a deliberate plan.

Neither conclusion need rest on implication or statistics, as there is direct evidence: in the case of Fort Pillow, sworn statements by dozens of eyewitnesses to the killings. Moreover, Fort Pillow was but one instance of Confederates murdering prisoners in the first half of 1864, including at several of the skirmishes Marvel’s article mentions. A question is whether the murders reflected increasing desperation on the part of the Confederacy, or were they the natural acts of a tribal people, who treat nonmembers of the tribe as subhuman? In either case, it’s time we stopped coddling the Confederacy by whitewashing its atrocities, many of them proven by the words of the Confederates themselves.

John Braden

Fremont, Michigan

Ed. Thanks for your note, John. We asked William Marvel if he cared to respond. He writes: “While trying to make dispassionate inquiries into the Saltville massacre, over three decades ago, I learned that some people are not satisfied by anything short of reflexive and unreflective confirmation followed by unmitigated condemnation. Apparently even the suggested addition of incriminating statistical evidence to the eyewitness testimony can somehow be contorted into ‘coddling’ Confederates.”

* * *

William Marvel’s “Rebel Revival” had me hooked from the opening paragraph, in which he dealt with the account of Captain Thomas Hines. Marvel’s article was a complex story told eloquently and succinctly.

Likewise, the tit-for-tat exchanges between brothers William T. and John Sherman over slavery, abolition, and voting rights in Bennett Parten’s article [“The Brothers’ War,” Vol. 14, No. 4] made for fascinating reading. (It almost made me want to find the correspondence of the Brothers Bragg over the same time.)

Lastly, the reason I love print was clearly demonstrated in the article that highlighted the artwork of Thure de Thulstrup [“A Talent for War,” Vol. 14, No. 4]. Digital can never come close to this.

John Grady

Via email

KUDOS

Thank you for your excellent publication. I look forward to receiving each issue. The scope of your magazine is impressive. In the Winter 2024 issue I especially enjoyed the article “A Talent for War” about the artist/illustrator Thure de Thulstrup. Your annual “Best Civil War Books” roundup keeps me abreast of the hard work talented authors give to the context of the Civil War. Finally, kudos to Bennett Parten and his article “The Brothers’ War.” It is an example of the fine work The Civil War Monitor presents. It is an in-depth and well-researched article that gives the fascinating backdrop of these two Sherman brothers. This national conflict was so much more than battlefield tactics over a period of four years. It was and continues to be a battle over our founding documents. Thanks for presenting a fuller understanding of what makes our struggle for independence both civil and uncivil.

Joel Quie

Via email

* * *

I would like to take the time to tell you how much I enjoy the Monitor and how much I have learned from your various articles. The book essays are so helpful in choosing new books for my library. I always look forward to the arrival of the Monitor. Thanks for an excellent magazine.

Lorna Williams

Via email

THE IMPORTANCE OF PRESERVATION

I recently read American Battlefield Trust president David Duncan’s short article about the “Big Tech Threat” that threatens the Second Manassas battlefield [“Preservation,” Vol. 14, No. 4].

I wanted to take the time to write and thank him for his (and his organization’s) efforts in the fight. Just now, I made a small donation to this effort, and the work of the American Battlefield Trust in general. I would sincerely love to do more, but since I’m not an American resident I struggle to find other meaningful ways of helping.

Please know that all over the world people (like me) are hoping the Trust succeeds in its efforts to preserve battlefields all across the U.S. These battlefields mark important chapters in U.S. history and in some ways also in world history. The world would not be the same without the U.S. and for what it stands. History means something, at least to me. And so it should to everybody.

Keep up the good work.

Daniel van Schijndel

Via email (from The Netherlands)

MARBLE MAN MUM

In response to Stephen Cushman’s article “Robert E. Lee’s Unwritten History” [Vol. 14, No. 3]: Why didn’t Robert E. Lee write a memoir? Answer: Lee was a man who made history, not one who wrote about it. He wanted to live in the present. Like Henry Ford indelicately said, “The only history that is worth a tinker’s damn is the history that we make today.”

I personally know a businessman who in his later eighties gave his very successful business to his two daughters. The last time we spoke was after his wife of 50-plus years passed. I said, “Duke, what are you going to do next?” He answered, “I bought an old church and am having it renovated. Maybe I’ll become a minister.” He has a new girlfriend and I expect that he will marry her. Duke always looked forward. So did General Lee.

Roger Domer

Laurel, Maryland

* * *

In response to the article as to why Robert E. Lee did not write a memoir: I believe plain and simple he did not do so because of his great humility, which was a product of his deep religious faith. It is my understanding that Lee practiced daily prayer, read the bible, and encouraged army chaplains to convert and distribute bibles to his soldiers.

Many other military men wrote memoirs of their wartime experiences out of a thirst for notoriety and fame. Lee chose not to because he lived of the spirit and not of the flesh, thus showing great humility.

Lee was called to Gloryland at the relatively young age of 63. He fulfilled his duty to his Lord and glorified him not by writing his memoirs or winning the Civil War, but rather by winning the greatest battle of all: the saving of souls.

Leonard Romero

Pasadena, California

* * *

I have recently concluded that despite Robert E. Lee’s reputation, he simply could not determine when the war was over and therefore is nothing more than an irresponsible killer. I’m so tired of hearing about him.

R.H. Flint

Golden, Colorado

USCT OFFICERS’ MOTIVES

While Andrew Bledsoe’s article [“Crossroads: A Burdensome Decision,” Vol. 14, No. 3] was an interesting one about the consequences for the men who joined the U.S. Colored Troops, I think he overstepped when he presumes to know the hearts of the white soldiers who volunteered to command such units. Public opinion is not a fact. No one knows what was in the hearts and minds of any soldiers. I find there is a troubling trend to impugn the motives of any white person who took a step in the direction of abolition, civil rights, etc. Why is it so important to downplay and even deny the good intentions and honorable motives of white Americans toward slavery, emancipation, civil rights, and black Americans? Hundreds of thousands of Union troops suffered and died during the Civil War—and revisionist historians would even take that noble intention away from them? They gave their lives. Isn’t that enough to satisfy? If Bledsoe has concrete proof from white soldiers’ testimony that they agreed to command USCT units only for personal gain, please reply to this letter. Otherwise, writers should be more careful about claims they like to throw around and editors should press them for the facts, rather than their opinions.

Toni Criscuolo

Via email

Ed. Thanks, Toni, for your letter. We asked Andrew Bledsoe if he’d like to respond. He writes: “Any researcher spending even a small amount of time among the sources will find that the motivation to pursue and accept a USCT commission could vary greatly. Certainly, many white officers were driven by a sense of justice, a desire to prove the racial worth and equality of black soldiers, a desire to restore the Union and achieve emancipation, or some combination of these noble aims. Even so, the historical record is replete with examples of ambition, self-interest, pride, and other, less admirable traits than a desire for Union and freedom for the enslaved driving these men to pursue command roles in USCT units. As I demonstrate in my 2015 book, Citizen Officers, pay alone proved an important incentive for men to seek commissions. Union captains received $115.50 per month, first and second lieutenants received $105.50, and staff officers usually received an additional allowance of $15 per month for expenses. Company-grade officers received nearly 10 times more per month than a typical private. This does not account for the added increase in privileges and prestige accompanying commissions. Small wonder, then, that Union soldiers such as Illinoisan A.M. Greer were, in 1863, bemused ‘to see men who have bitterly denounced the policy of arming negroes … now bending every energy to get a commission.’

Even the most famous USCT officer of them all, Robert Gould Shaw, had conflicted and complicated motivations for accepting commission as colonel of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. In letters originally censored by his mother, and only later revealed in their original form, Shaw used the term ‘nigger,’ referred to blacks as ‘darkies,’ and even called himself a ‘nigger colonel.’ Moreover, Shaw initially rejected the offer of Governor John Andrew to command the 54th Massachusetts. Only later did a conflicted Shaw accept, after his mother appealed to his sense of honor; Shaw also admitted to his future wife, Annie Haggerty, that he agreed to the proposal because it would be easier to get a furlough as a colonel than a mere captain. I mention this not to denigrate Shaw’s ultimate sacrifice or the service of any USCT officer. I merely wish to illustrate that even Shaw, rightfully lauded as an abolitionist hero, had complicated and sometimes contradictory reasons to pursue a USCT commission. Human motivation and behavior are almost never simple, and these men were no exception; to reduce them to mere caricatures risks doing them, and our historical understanding, a great disservice.

As to the intimation that historians who examine both old and new evidence and reevaluate received interpretations of the past based on that evidence are ‘revisionists,’ then I respectfully conclude by affirming that this sort of revisionism is, very properly, the essence of the historian’s art.”

A READER’S TRAVEL TIP

I read and enjoyed the results to your recent travel survey [“Profile of a Civil War Traveler,” Vol. 14, No. 3] and wanted to share a U.S. history vacation my family took the previous summer. Rather than focus on one Civil War battlefield, we decided to see as many battlefields (plus other major history sites) as we could squeeze into a three-week driving vacation.

We met at Charleston, South Carolina (flying in from Texas and California), and rented a car at the airport. The next day, we took the ferry boat to Fort Sumter. After touring the rest of Charleston, including the Old Slave Mart Museum, we headed north to Virginia.

Next up was the Petersburg National Battlefield outside of Richmond. To keep the U.S. history theme, we also visited the nearby Yorktown Battlefield, Colonial Williamsburg, and Jamestown. We proceeded to Appomattox, site of Robert E. Lee’s surrender, then to Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s home. We then made two quick side trips to Antietam National Battlefield and Harpers Ferry. Finally, the climax of our trip was Gettysburg, where we took in the annual battle reenactment.

Our travels were lots of fun and extremely educational, but required lots of planning and research. I hope our trip will inspire others to take a grand tour of U.S. history sites and Civil War battlefields. (Note: We stayed at Airbnbs and hotels the whole time.)

Keith Comfort

Houston, Texas

OOPS

There seems to be an error on page 20 of the Fall 2024 issue [“Cost of War,” Vol. 14, No. 3]. Please forgive me if I am wrong, but you identified the carving of the insignia on the Gettysburg battlefield souvenir as belonging to the Army of the Potomac’s V Corps. I believe it is the II Corps’ trefoil badge. I have been following the history of the II Corps’ 5th New Hampshire Infantry for many years. Please take a look and see what you think.

May I add that I very much appreciate and enjoy the Monitor. As a history teacher of over 30 years, I find something new and inspiring in every issue. Thank you for keeping history alive and relevant.

Ginny L. Dumais

Loudon, New Hampshire

Ed. Thanks for your letter, Ginny. You’re correct: We did misidentify the corps badge shown on the Gettysburg “relic tower”—it is that of the II Corps. For the record, the tower also contains carvings of the insignia of the Army of the Potomac’s V, VI, and XII Corps, though none of these are visible in the photo we highlighted. Our apologies for the error—and our thanks for the kind words!

A QUESTION ABOUT CASUALTIES

I question D. Scott Hartwig’s claim in his recent article about the Battle of Antietam [“The Bloodiest Day,” Vol. 14, No. 3] that 90 percent of all casualties in the Civil War were inflicted by small arms fire, about 10 percent from artillery, and less than 1 percent from hand-to-hand combat. “All casualties” would of course include fatalities. I recall that on a visit to the National Museum of Civil Medicine in Frederick, Maryland, an exhibit sign on field hospitals noted that 95 percent of “all wounds” in the war were caused by minie balls, with artillery and hand-to-hand combat accounting for the rest. These wounds were inflicted on men who made it to the field hospitals for treatment. This does not translate to 95 percent of all fatalities caused by small arms fire.

I think it is safe to say that soldiers who were hit by canister, artillery shells, and cannon balls tearing through the lines, along with men who were skewered by bayonets or had their heads smashed in with clubbed rifles, were far more likely to be killed outright or die soon from their severe wounds before they ever reached a field hospital than soldiers who were struck by less-lethal minie balls. When we consider the huge number of casualties caused by artillery at places like Gaines’ Mill, Malvern Hill, Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Stones River, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg, among many others, it seems highly unlikely that artillery accounted for a small fraction of all casualties, let alone fatalities, in the war.

Dennis Middlebrooks

Brooklyn, New York

Ed. Thanks for the letter, Dennis, which we forwarded to Scott Hartwig for comment. He writes: “Dennis is correct that I should have written ‘all wounds’ rather than ‘all casualties’ since the statistic that approximately 90 percent of all wounds were inflicted by small arms, about 10 percent by artillery, and less than 1 percent from hand-to-hand combat, is from The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, and is derived from those wounds treated at field hospitals. However, since approximately three to four soldiers were wounded on average for every soldier killed, the statistical breakdown for all wounds treated is from a very large statistical sample and therefore likely applies to all casualties. My point in the article, though, was that while this statistical spread probably holds true for the overall war, certain battles where artillery had a prominent role—such as Malvern Hill, Antietam, and Gettysburg—likely deviated from it, with artillery inflicting more than 10 percent of casualties in those instances.”

MEDAL OF HONOR

In the Fall 2024 issue article titled “A Package from Home” [“In Focus,” Vol. 14, No. 3], the author uses the phrase “Congressional Medal of Honor.” I would like to offer that you and your contributors refrain from doing so in the future. Unless you provide me information to the contrary, the correct title of our nation’s highest award for valor is “Medal of Honor.” As far as I know, it’s always been titled that way. It’s kind of disrespectful, and lazy, to refer to our highest award—both the person receiving it and the medal itself—incorrectly.

Overall, a very interesting and informative issue.

J.H. Thompson

Ogden, Utah

Ed. Thanks for your letter, J.H. We reached out to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, with your question about the medal’s proper name. Senior Director of Archives, Collections & Museum Laura S. Jowdy responded: “Historically, the Medal of Honor has been referred to as both the ‘Congressional Medal of Honor’ and the ‘Medal of Honor.’ The modern name is simply ‘Medal of Honor’ and it is the preferred and official terminology.” We’re happy to use the latter term whenever referring to the award in future.

Letters to the Editor

Email us at [email protected] or write to The Civil War Monitor, P.O. Box 3041, Margate, NJ 08402