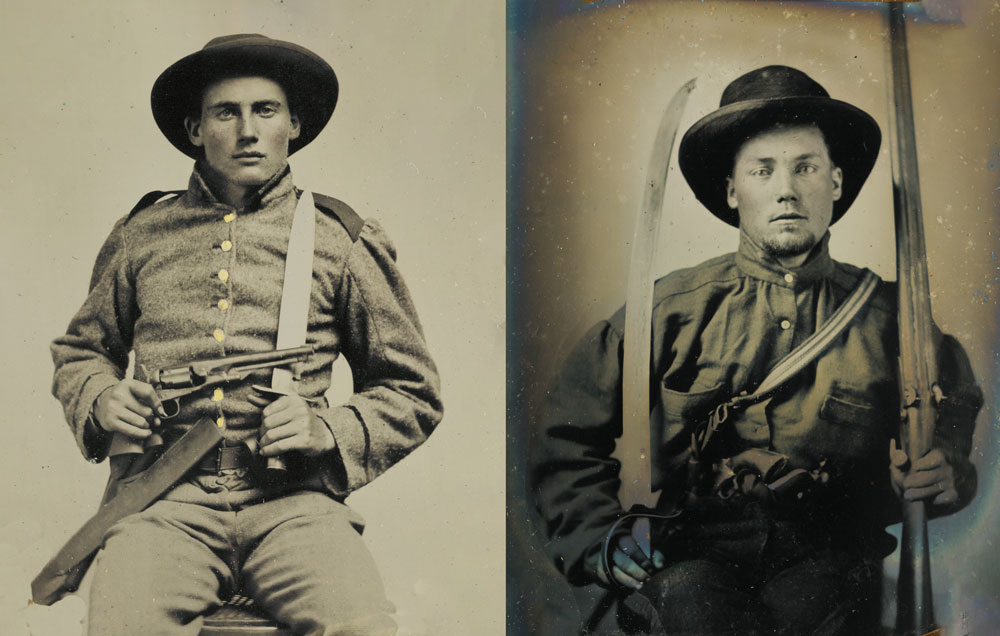

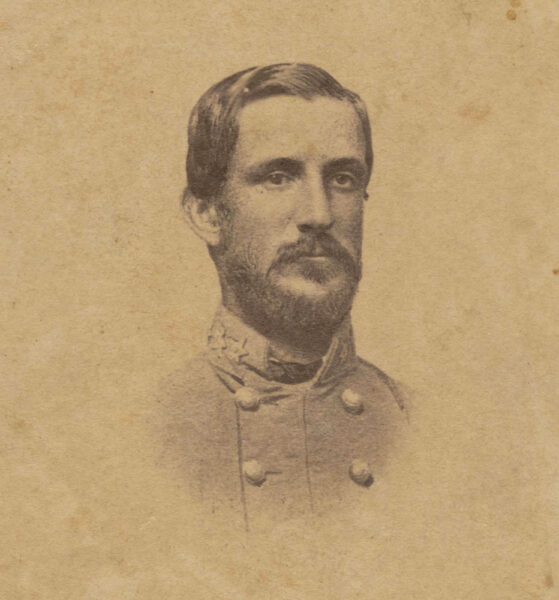

Two black and white photographs of Confederate soldiers. Library of Congress

Library of Congress

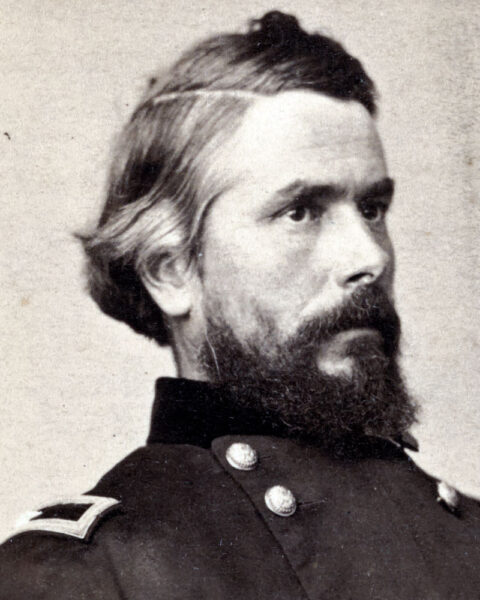

Freshly escaped from a Union prison, Captain Thomas Henry Hines visited the capital of the Confederacy in January and early February 1864, detecting an atmosphere of “unusual gayety” pervading Richmond. “Parties and balls were the order of the day,” he wrote a year later, describing festive levees held at the president’s house every Friday. Fashionable gentry and government functionaries buoyed their spirits at the end of each disappointing week with wry wit and the rustle of crinoline, but behind that façade Hines ascertained “a shadow of deep gloom on the heart of the most hopeful.” The southern revolution had come to such wreckage that whispers of inevitable defeat suffused the conversations of civilians.1

Union armies controlled most of coastal Virginia and North Carolina, held a solid foothold in South Carolina, and occupied or dominated all but the mountainous easternmost fragment of Tennessee. Piercing the Mississippi River Valley from above and below, they had divided the Confederacy into eastern and western halves. Northern and western Louisiana, southern Arkansas, and most of Texas remained independent, but isolated, and Confederate forces there were heavily outnumbered, as they were on every front. The Army of Tennessee had suffered a humiliating rout outside Chattanooga at the end of November 1863, fleeing into the mountains of Georgia. Even General Robert E. Lee had shed his aura of invincibility the summer before, as his battered Army of Northern Virginia limped back from his brash foray into Pennsylvania.

Captain Hines believed that the fighting men of the South shared none of the civilian population’s despair, but he had not spent much time with organized troops since the previous July, at the height of Confederate hopes. Morale had already plummeted in almost every bivouac when January’s bitter cold settled on the encampments of ragged Rebels. By February, a steady stream of deserters had begun drifting into Union lines to take advantage of a new offer of amnesty from President Abraham Lincoln, and still more were slipping away to their homes, giving up the fight as hopeless.2 Lee’s proud army bled a trickle itself, and Lee approved a flurry of executions in an effort to curb the trend.3 “Victory nowhere and defeat everywhere for us,” lamented an Alabama adjutant in the Army of Tennessee. “We will be subgigated yet,” predicted a veteran Georgia infantryman, “just as shore as abc.” References to the “darkest hour” of the Confederacy sprinkled the diaries and letters of soldiers and civilians from the Tidewater to Texas.4

Wikimedia Commons (Richmond); Heritage Auctions/HA.com (Hines)

Wikimedia Commons (Richmond); Heritage Auctions/HA.com (Hines)In January and February 1864, Confederate officer Thomas Henry Hines (above left) visited Richmond (depicted above in a wartime issue of Harper’s Weekly) and found the city’s jovial atmosphere masked “a shadow of deep gloom” over the war’s progress.

As though to demonstrate the utter helplessness of the South, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman gathered a force of nearly 27,000 Union infantry, cavalry, and artillery at Vicksburg, and on February 3, 1864, that makeshift army started across Mississippi in two columns. Sherman anticipated that no more than 20,000 Confederate troops could be collected in the entire state to face him, and that was a generous estimate. At first only two depleted brigades of cavalry confronted Sherman’s march, with one brigade challenging each column, hardly slowing them even after a third small brigade joined in the resistance. Yankees entered the capital city of Jackson on the evening of February 5, for the second time in seven months.5

The next day, Union troops burned all the public buildings except the state capitol and city hall, and many of them burst into private homes as well, carrying clothing, bedding, books, and furniture into the streets. As this raid began, Sherman reasoned that he had a right to do as he wished with “houses left vacant by an inimical people,” excepting only “dwellings used by women, children, and non-combatants” if they “remain in their houses and keep to their accustomed business.” With Confederate armies seemingly no longer capable of entering Union territory to inflict retaliation in kind, Sherman made no special effort to enforce that exception. Homeless families and the smoldering ashes of their houses littered the wake of his march to Jackson, and as he camped on the edge of that town an Illinois soldier saw smoke billowing from at least 20 homes.6

Devastation marked Sherman’s trail eastward along the corridor of the Southern Mississippi Railroad, with depots, plantations, and whole towns left in flames all the way to Meridian. Heavily outnumbered Confederate infantry retreated ahead of their cavalry, which could do little more than harry the invaders, who took special revenge for the affrontery of resistance. Near Decatur, Rebel cavalrymen slowed the Union wagon train by killing some of the teams, and one of the Yankees admitted “we burnt the town to pay them for it.” Near the town of Morton, a woman and her children were driven from their home on the suspicion that her husband had gone off as a bushwhacker, and the house was put to the torch, leaving them nothing but the clothing on their backs. A similar scene played out at Meridian, when a woman was accused of having insulted a Yankee soldier.7

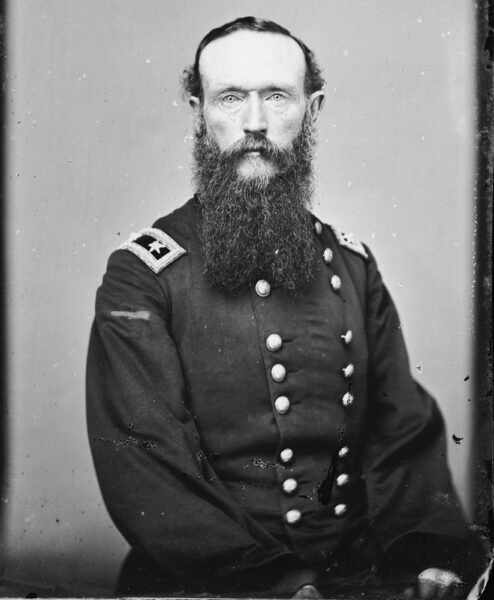

Library of Congress

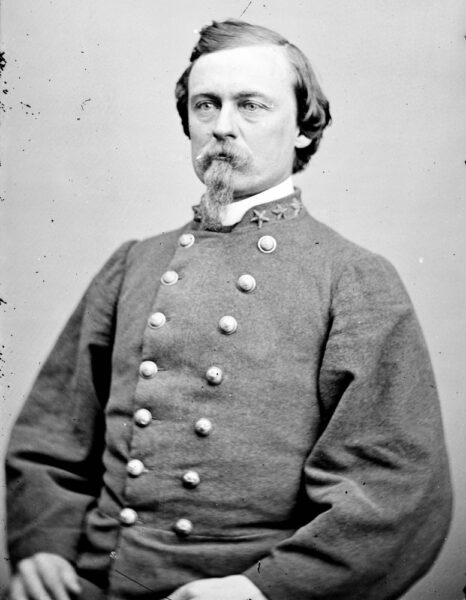

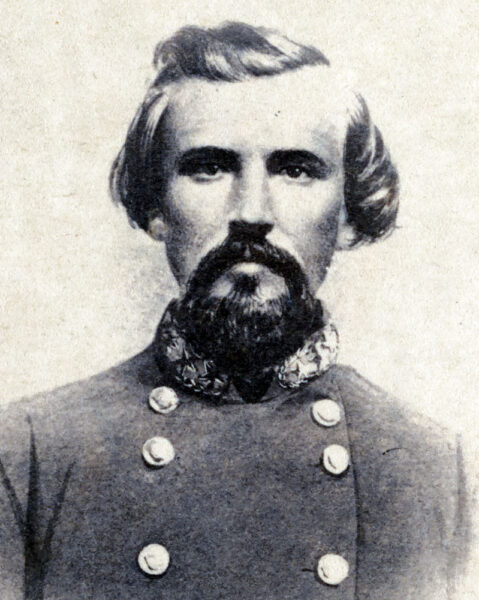

Library of CongressBrigadier General Joseph Finegan, whose outnumbered Confederate troops defended against the Union foray into Florida in February 1864

The raiders rested at and near Meridian for several days, with detachments radiating outward to tear up railroad tracks, burn bridges, and demolish whatever military infrastructure the retreating Rebels had neglected to destroy. Confederate cavalry remained on the periphery, but most of the infantry withdrew toward Demopolis, Alabama, to await reinforcements and stand in the way of any advance toward the industrial center at Selma; a smaller detachment had turned south, toward Mobile. If Sherman proceeded toward either of those alluring targets, the forces on hand for their defense would almost certainly have been insufficient.

Although he seemed free to go wherever he pleased in a region where defense had become almost a pretense, Sherman thought better of venturing deeper into Dixie. Later he disavowed any such temptation, citing both his promised participation in the scheduled launch of another raid into Louisiana and the difficulty of caring for his wounded, if he were forced to fight a battle so far from river transportation. On February 18 he instructed the commanders of his columns to prepare for the journey back to Vicksburg, anticipating no interference from feckless Confederate forces.8

It still looked as though the Yankees would be able to waltz across north Florida, brushing Finegan aside and destroying the important railroad bridge over the Suwannee

River.

A sudden Union foray into Florida had exposed equal weakness in the defenses there. Major General Quincy Gillmore, commanding forces in the Department of the South, coveted the northern counties of that state as a recruiting ground for his numerous regiments of U.S. Colored Troops, and he was even more anxious to deny Confederate armies the vast herds of beef cattle there. President Lincoln, meanwhile, saw Florida as an inviting experiment in reconstruction; his amnesty proclamation included an option for southern Unionists to form new, loyal state governments if enough citizens took the oath of allegiance to equal 10 percent of each state’s vote tally from the 1860 election. When Gillmore learned of the president’s wishes, he promptly organized an expedition from his garrisons on the South Carolina coast and loaded it on steamers.9

Library of Congress

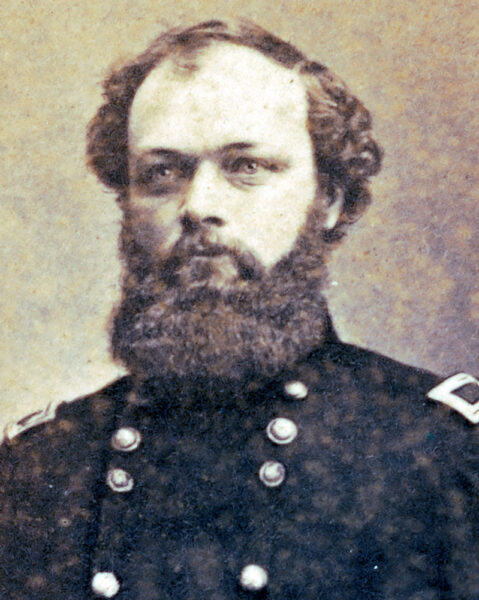

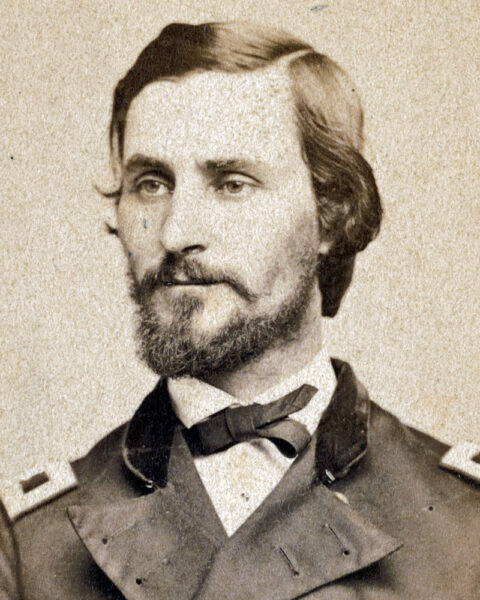

Library of CongressQuincy Gillmore

The flotilla left Hilton Head on February 5, 1864, and the first transport docked at Jacksonville on the afternoon of February 7. Several companies of the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry spilled ashore, chasing a handful of Confederate videttes out of town, and the next day seven regiments of Union infantry strode into the interior behind a vanguard of Massachusetts cavalry and mounted infantry. That force alone outnumbered all Confederate troops in Florida by about 4 to 1. Rebels encamped north and west of Jacksonville hastened toward Lake City, where Brigadier General Joseph Finegan assembled a thin line of defense and wired frantic appeals for help to his department commander in Charleston, General Pierre G. T. Beauregard.10

Leading a squadron of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry and the mounted 40th Massachusetts Volunteers, Colonel Guy V. Henry outdistanced his infantry supports, sweeping up a few prisoners and some artillery. At dawn of February 9 his “light brigade” galloped into the rail junction at Baldwin, 20 miles inland from Jacksonville. That afternoon the commander of the expedition, Brigadier General Truman Seymour, rode into Baldwin, and General Gillmore followed that evening for a late-night council before turning back to his own headquarters, leaving Seymour in charge. The next day, Henry’s mounted men trotted another 20 miles to Sanderson Station. In the wee hours of February 11 they continued toward Lake City, 24 miles away, passing Olustee Station in the gloaming, and then the big lake called Ocean Pond. They ran into Confederate pickets a couple of miles short of Lake City. Finegan had collected about 600 men to put in line, but Henry did not field many more than that himself, so he fell back on Seymour’s infantry, at Sanderson.11

Library of Congress

Library of CongressTruman Seymour

It still looked as though the Yankees would be able to waltz across north Florida, brushing Finegan aside and destroying the important railroad bridge over the Suwannee River. That seems to have been the program Gillmore outlined during his night at Baldwin, but Seymour fell into an apparent panic, fretting over provisions and being cut off even before Henry reported his observations at Lake City. Seymour wrote Gillmore a nervous note, discouraging any further advance and proposing a retreat to Baldwin. Gillmore, who still lingered at Jacksonville, revised his orders to comply with Seymour’s opinion, then sailed for Hilton Head.

Gillmore had hardly set to sea before Seymour reversed himself. As though suddenly relieved of any anxiety over his ability to handle his opponents or supply his own troops, he cited the importance of goals he had belittled only days before, announcing his intention to dash into the interior with his main body. He asked for a demonstration by navy ironclads up the Savannah River, to distract Confederates who might otherwise come to Finegan’s aid, but while he considered the diversion “of great importance” to his success, he put his troops in motion before he even knew whether the navy could cooperate. As soon as Seymour’s bizarre letter reached Hilton Head, Gillmore dispatched his chief of staff by steamer to countermand the movement—but a storm blew up. By the time the steamer reached Jacksonville, it was too late.12

On Saturday morning, February 20, Colonel Henry’s horsemen led the march out of what was then the advance post, on the South Prong of the St. Mary’s River. Eight infantry regiments and three batteries of artillery followed, giving Seymour what he estimated as “near 5500” men. Henry’s little brigade halted at Sanderson, 10 miles out, starting again when the infantry caught up, around noon. A couple of hours later, the first shots echoed from the pine forest as the leaders came up against skirmishers of the 2nd Florida Cavalry.13

By then, Finegan had been reinforced by the arrival of some of his own scattered Florida troops and a brigade sent from South Carolina by Beauregard. That gave him almost exactly the same number of men as Seymour, in similar proportions of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. He distributed them across the Lake City Road and the railroad, behind rudimentary earthworks near Ocean Pond, but as the enemy approached Finegan pushed one Georgia regiment and part of another a couple of miles ahead, to a point where the road and railroad tracks converged. When his cavalry skirmishers backed up to that position, they cantered off to the sides and the Georgia infantry took over the fight, sparring with a few companies of the 7th Connecticut Infantry, armed with seven-shot Spencer carbines.14

Seymour was caught off guard, with his column strung out too far. Colonel Joseph Hawley, commanding the leading brigade, had only his own depleted 7th Connecticut, the recruit-laden 7th New Hampshire, and the inexperienced 8th U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). Finegan forwarded three more regiments to the front under Brigadier General Alfred Colquitt, and Hawley ordered the New Hampshiremen into line, but they began to deploy incorrectly. Hawley tried to redirect the regiment, but under heavy fire the tangled companies disintegrated. That left only the recruits of the 8th USCT, commanded by Colonel Charles Fribley, and they went into line smoothly enough, but intense Confederate musketry started dropping them by dozens. Then the 7th Connecticut ran out of ammunition, leaving Fribley and two artillery batteries to contend with the rapidly expanding Rebel line.15

An hour into the fight a second brigade of three New York regiments fanned out to the right of Fribley’s beleaguered men, but Colquitt stretched his left far enough to overlap them. Fribley had just started withdrawing his regiment when he was killed, and the withdrawal turned into a rout, endangering the Union left flank and exposing the artillery there to a devastating fusillade from advancing Confederate infantry. The 54th Massachusetts leaped into that gap. When concentrated fire from the fully engaged Confederate command wore down the New York brigade, Seymour replaced it with his last regiment, the 35th USCT, but by then the front was falling steadily backward. Georgia and Florida cavalry came up to rake the Union flanks, and as the sun set Seymour’s entire line funneled into frantic retreat. More than a third of his men had been killed, wounded, or captured, and a third of his artillery and small arms were left on the field. Only a feeble pursuit by Finegan’s cavalry saved the Yankees from far worse disaster, and they marched through the night to reach their former camp, resting briefly before continuing their flight toward Jacksonville.16

Lopsided as the Confederate victory was, it had been a relatively minor affair, and Beauregard seethed over the failure of Finegan’s cavalry to wreak significant damage on Seymour’s beaten and disorganized column as it retreated through the night. Defeating a Union army of equal size and driving it away nevertheless represented a noteworthy achievement at this stage of the war, and when word of the fight leaked out of isolated Florida it raised some dismay among officials of the U.S. government and much glee at all levels of Confederate society. Delay in spreading the news helped to enhance appreciation for it, because by the time it reached the far corners of Rebeldom it was amplified by reports of other, later victories.17

Before leaving Vicksburg, Sherman had directed Brigadier General William Sooy Smith to gather more than 7,000 Union cavalry outside Memphis and strike for Meridian, following the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and tearing it up as he went.

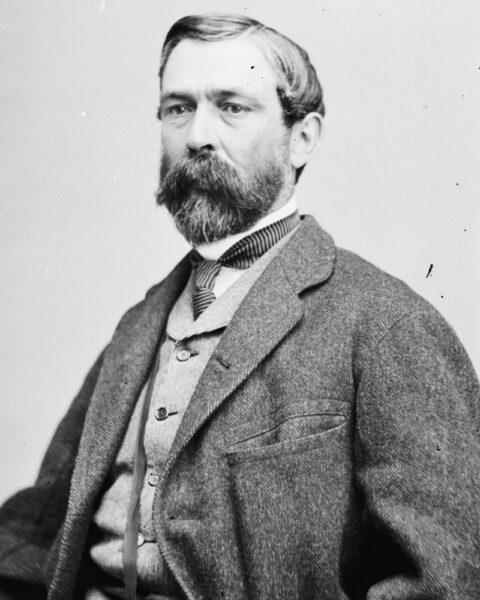

One of those victories cast a shadow over Sherman’s triumphant return from Meridian. Before leaving Vicksburg, he had directed Brigadier General William Sooy Smith to gather more than 7,000 Union cavalry outside Memphis and strike for Meridian on a route perpendicular to Sherman’s march, following the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and tearing it up as he went. Barely one-third as many Rebel horsemen stood in his way under Nathan Bedford Forrest, lately promoted to major general and sent from the Army of Tennessee to raise a new command in west Tennessee and north Mississippi. Sherman wanted Smith to meet him near Meridian around February 10. As it happened, Smith waited for the arrival of a tardy brigade, and did not even leave his camp in Tennessee until February 11. He used up eight days covering the 120-mile distance to the Mobile & Ohio, at Okolona, not even halfway to the rendezvous at Meridian.18

Smith’s cavalry found the Mississippi prairie one vast granary and swarmed one plantation after another, emptying barns, corn cribs, and smokehouses as women begged for enough to feed their children. The Yankees burned what they could not use or carry, and sometimes the barns or the house went up with it. One planter who tried to resist them was left dead on the roadside, while his killers burned his house. General Smith himself offered a reward for the first man caught in such “incendiarism.”19

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAs the Union advance into Florida faltered, another Union force in Mississippi met trouble at the hands of Confederates commanded by newly minted Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

The brigandage that Smith’s raiders engaged in weakened their discipline generally, and Smith worried that plundering had so demoralized two of his three brigades that he would not be able to depend on them in a fight. An exaggerated estimate of available Confederate forces heightened Smith’s anxiety, and he was easing his way down the rail line toward West Point on the morning of February 20, anticipating meeting the enemy in equal numbers. Four brigades of Rebel cavalry did start north from Meridian that day, with which Forrest hoped to cut Smith off and capture him, but rumors of those reinforcements persuaded Smith to abandon his mission and head for home; by the morning of February 21, his wagon train was already rolling north. As soon as the Union cavalry followed, Forrest turned in pursuit, outdistancing his reinforcements and the ammunition supply he badly needed. For most of the day he raced ahead of his main body with only an escort, or a small regiment, but so doggedly did he tail the Yankees all day, and so ferociously did he strike at their column, that the retreat became a chase.20

Forrest’s men carried mainly Austrian rifles with greater range than the Federals’ carbines, and while most of them had but 40 rounds apiece they could punish Smith’s cavalrymen from a safer distance. Only when it grew too dark to tell friend from foe did Forrest call a halt, but his men were back in the saddle early on February 22, catching up with Smith’s rear guard below Okolona. Driving that rear guard through town, they found a full Union brigade in line of battle across the escape route to the northwest. Forrest rode to the head of his nearest brigade and led it in a headlong charge against those Yankees, knocking them back into their supports and capturing scores of them as the rest bounded away, leaving a six-gun battery in their wake. All day the Federals fled over hillier ground, leaving an ambush behind now and then to slow the pursuit, and one of Smith’s brigadiers admitted that their march “became less a retreat and more nearly a rout” every hour. Forrest only relented after 10 miles, when his men began running out of ammunition.21

Library of Congress

Library of CongressWilliam Sody Smith

Smith returned to his camp in Tennessee more quickly than he had left it, now poorer by several hundred men and a couple of thousand horses. A delighted young Rebel woman described the survivors as “perfectly demoralized,” and southerners in and out of uniform interpreted Smith’s repulse as the reason Sherman turned back from what they supposed had been meant as an attempt to take Mobile. Coming simultaneously with news of Finegan’s victory in Florida, the report of Forrest trouncing a Union force more than twice the size of his own ignited a spark of hope around many a Confederate hearth and campfire.22

Those cheering tidings had no sooner reached anxious ears than another affair in the mountains of northwest Georgia seemed to corroborate the impression of recovering Rebel military prowess. On the logic that Sherman’s rampage across Mississippi might draw Confederate reinforcements from the Army of Tennessee, Ulysses Grant—soon to be lieutenant general and general-in-chief—directed Major General George Thomas to test the defenses of that Rebel army’s winter camp around Dalton, Georgia, and seize that place if possible. From his headquarters in Chattanooga, Thomas sent four infantry divisions and two mounted brigades to determine whether his opponent could be expelled from the Dalton line. Yankees drove in Rebel pickets on February 23, and spent the next two days trying to break through imposing mountaintop defenses on two different fronts. General Joe Johnston had taken command of the Army of Tennessee less than two months previously, finding it outnumbered at least 2 to 1 by Thomas’ army, but under presidential orders he had sent heavy reinforcements to confront Sherman. The divisions moving against him numbered only a few thousand less than all the infantry he had on hand. His remaining men nevertheless held their ground after an initial breakthrough in a weakened sector, inflicting heavy casualties during their assailants’ most ambitious assault. When the Union divisions withdrew, leaving some of their dead behind, Dalton’s defenders laughed off reports that the operation had been a mere reconnaissance-in-force, calling it another victory in the recent series and rejoicing that their new commander would stand and fight. Spirits began to soar in that army, which had only weeks previously labored under the worst morale in the Confederacy.23

Those cheering tidings had no sooner reached anxious ears than another affair in the mountains of northwest Georgia seemed to corroborate the impression of recovering Rebel military prowess.

General Thomas’ troops had not settled back into their camps in Tennessee before Benjamin Butler inspired a Union fiasco in Virginia that backhandedly burnished the reputation of Rebel arms. Butler, one of the earliest and least deserving of Lincoln’s volunteer major generals, had attempted early in February to rescue Union prisoners on Belle Isle, in the James River opposite Richmond. Based on reports from a loyal Richmond resident, Butler sent a couple of thousand cavalry from his command at Fort Monroe toward that city with orders to free the prisoners, destroy the navy yard, tear up the railroads, and capture President Jefferson Davis at his official residence. Those horsemen reached the Chickahominy River, 10 miles out from Richmond, in the wee hours of February 7, finding a stronger guard than anticipated. Confederate volleys emptied a few saddles, and the raiders turned back the way they had come.24

Library of Congress

Library of CongressOn the heels of Confederate successes in Florida and Mississippi in February 1864, Ulysses S. Grant directed Major General George Thomas to test the defenses of the Confederate Army of Tennessee’s winter camp around Dalton, Georgia.

Butler’s botched raid sparked President Lincoln’s ambition for a more ambitious attempt, in which the prisoners might be released while notices of his amnesty proclamation were distributed deep in the Old Dominion’s interior. The concept of capturing the Confederate president lingered in this plan, at least unofficially, and Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick was selected to lead it. He left the camp of the Army of the Potomac on February 28 with upward of 4,000 cavalry and artillery, riding through that night and the next day. Several hundred men under Ulric Dahlgren, a 21-year-old colonel, branched off to cross the James and attack from the south while Kilpatrick struck from the north. So swollen was the river by recent rains that Dahlgren saw there was no hope of fording it. By the time he arrived at Richmond, late on the afternoon of March 1, Kilpatrick had already given up on him; after feigning an attack on the city’s defenses, Kilpatrick had turned for home.25

Dahlgren made his own stab on another road into the city near evening, sparring with some mobilized clerks and artisans before riding off into a snowstorm at such a gait that he and the hundred men nearest him left the rest of the command behind in the darkness. Pursuing Confederate cavalry surprised Kilpatrick’s sleepy troopers in their snow-covered blankets that night, capturing scores of them and leaving even more on foot. After mounted Rebels hit them again the next day, Kilpatrick abandoned hope of reaching the Army of the Potomac and turned for the safety of Butler’s command. Eventually the bulk of Dahlgren’s orphaned column caught up with Kilpatrick’s main body, but Dahlgren’s lost vanguard ran into an ambush where Dahlgren was killed and most of the rest captured. One-tenth of those who had begun the raid did not return, and one-sixth of the arms and horses were lost, while few of the horses that did survive were sound enough for further service. Nothing had been accomplished, and many of those sent to release Union prisoners joined them on Belle Isle. Worse still, papers found on Dahlgren’s body betrayed the plan for the liberated prisoners to burn Richmond and capture—or, implicitly, kill—Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. Kilpatrick’s failure further enhanced Confederate confidence, and Dahlgren’s murderous instructions fueled southern fury.26

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUlric Dahlgren

While Kilpatrick led his men to disaster, General Sherman met with Major General Nathaniel Banks, who had replaced Butler in command of the Department of the Gulf. Like Butler, Banks was a Massachusetts politician of dubious military merit, but Sherman agreed to lend him 10,000 men for a campaign up Louisiana’s Red River, driving into the military and industrial heart of the Trans-Mississippi. Major General Richard Taylor, the son of former President Zachary Taylor and commander of Confederate forces in western Louisiana, did not have over 8,000 men to defend his bailiwick. With Sherman’s troops, the army Banks would field, and the divisions Major General William Franklin was bringing up from southern Louisiana, Taylor would face four times that many Yankees.27

Taylor retreated steadily before those converging columns, losing a fort and a few hundred men below Alexandria. He fell back 30 miles from Alexandria, leaving his last squadron of cavalry at an advanced outpost, but a Union division captured almost the entire squadron after a fortuitous night march, forcing Taylor to withdraw 30 miles farther. He appealed for reinforcements from his department commander, Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith, and Smith ordered several brigades of cavalry to ride to his aid from Texas. Before that cavalry arrived, Taylor withdrew yet again, backing away to the vicinity of Mansfield, less than 30 miles from the Texas border. The Texas cavalry met him, badgering the Union advance relentlessly on a single-lane road surrounded mostly by dense forest. The Union column stretched nearly 20 miles, with cavalry and an undersized corps of infantry in front, widely separated from supporting troops. On the afternoon of April 8, Taylor struck. Union infantry came up, forming a line of battle below an intersection called Sabine Crossroads, but Taylor threw everyone into his attack and overlapped that line, sending it into retreat toward the baggage train, where jammed wagons blocked the road. The Federals bolted headlong through the woods and never slowed down until dark, when their pursuers ran up against a fresh division waiting in ambush.28

Most of the Union troops from the elongated column had reunited by morning at Pleasant Hill, a dozen miles below the previous day’s battlefield. With his infantry replenished by two divisions that Smith had sent from Arkansas, Taylor attacked Banks again on the afternoon of April 9, hoping to keep pressure on an army he knew was larger but assumed was demoralized. His Arkansas reinforcements bent the Union left nearly to the breaking point, but a surprise flank attack turned the tables and Taylor got the worst of it that day. Still shaken by the disaster at Sabine Crossroads, Banks overruled furious subordinates and ordered a retreat to the Red River at Grand Ecore. A fleet of Union gunboats and troop transports had steamed upriver from Grand Ecore toward Shreveport, but low water and harassment from Confederate cavalry threatened to trap it. By mid-April the entire expedition seemed to be in jeopardy—troops, ships, and all.29

Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn March 1864, Union forces advancing into western Louisiana during the Red River Campaign encountered Confederates commanded by Major General Richard Taylor, the son of former President Zachary Taylor.

Bedford Forrest, meanwhile, had followed up on his surprising victory in Mississippi with a raid to the banks of the Ohio River. Late in March he cowed the Yankee commander of Union City, Tennessee, into surrendering his entire 500-man garrison; then he launched an attack on Paducah, Kentucky. The Union commander there proved too obstinate, but Forrest’s assault brought the war back within sight of the free states. Two weeks later, back in Tennessee, he quickly subdued the isolated garrison at Fort Pillow, above Memphis, killing half the 600-man garrison and capturing the remainder. The disproportionate number of killed among Colored Troops implied an inclination to refuse quarter, but the capture of Union City and Fort Pillow enhanced the impression of a rising tide for the Confederacy.30

That perception grew stronger barely a week later, when Brigadier General Robert Hoke led a makeshift division of troops detached from Lee’s army against the town of Plymouth, North Carolina. Ten Union regiments under an aging brigadier defended the place, but after a three-day siege Hoke battered them into submission, taking upward of 3,000 prisoners, and an extemporized new Confederate ironclad sank a Union gunboat into the bargain.31

The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel HillRobert Hoke

Edmund Kirby Smith recalled the two Arkansas divisions from Taylor, taking his division of Texas infantry as well, and marched northward to expel another Union force from southern Arkansas. After much urging by Grant, now the Union general-in-chief, Major General Frederick Steele had collected some 10,000 men to operate against Smith from the northeast while Banks struck from the southeast. Leaving Little Rock late in March, he had taken refuge in Camden, Arkansas, on April 15, when provisions ran short. By late April his foraging parties had been so decimated by Confederates under Major General Sterling Price, and so many of his supply trains had been intercepted, that Steele decided to turn back for Little Rock. Smith chased after him with the divisions he had drawn from Taylor, ultimately catching up with him at Jenkins’ Ferry on the Saline River. On April 30 Steele’s rear guard fought off repeated attacks, inflicting staggering casualties before slipping over the river and hightailing it for home.32

Smith’s costly assaults allowed him to claim that he had driven Steele away, but that had been unnecessary. Steele was already retreating as quickly as he could, while Taylor might well have trapped Banks and his entire army with the troops whose lives Smith squandered in Arkansas. The fight at Jenkins’ Ferry had nonetheless reinforced the image of savage, indomitable Confederate forces. As May began, it seemed that catastrophe might still befall Banks, along with the Union gunboats and transports that had accompanied him.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressFrederick Steele

The results of military operations between February 20 and April 30, 1864, refute the once-traditional hypothesis that Confederate morale peaked in June 1863 and declined steadily thereafter. Ten weeks of unbroken Confederate success spawned a surge of confidence in all theaters on the eve of the spring campaigns. So rapid a recovery of Confederate prospects from the despondent days of December and January revived the Rebel heart at the brink of what appeared to be ultimate despair, renewing faith that the darkest hour augurs the dawn. Lee’s and Johnston’s soldiers faced the spring campaigns of 1864 with ardor restored by the string of victories inaugurated by Olustee, without which the steady backpedaling toward Atlanta and Richmond would more plainly have portended eventual defeat. Instead, the seemingly unquenchable defiance of southern arms bent northern will to the breaking point, leading even Lincoln to mourn toward the end of summer that the game might well be up.33

If not for that restored morale, Confederate resistance in Virginia and Georgia would likely have been less stubborn, and Union advances more rapid. Except for Forrest’s spring raid and the capture of Plymouth, all the Confederate victories from February through April had emanated from Yankee operations that were needless or badly executed, or both. Had all Union forces remained in camp through the third winter of the war, there might not have been a fourth.

William Marvel is the author of a score of books on different facets and figures of the Civil War, including The Confederate Resurgence of 1864, just out from LSU Press.

Notes

1. Notebook, Thomas Henry Hines Papers, University of Kentucky, entry dated March 14, 1865.

2. Janet Correll Ellison, ed., On to Atlanta: The Civil War Diaries of John Hill Ferguson (Lincoln, 2001), 3; James B. Vickery, ed., The Journals of John Edward Godfrey (Rockland, 1979), 67; Lee C. Drickhamer and Karen D. Drickhamer, eds., Fort Lyon to Harper’s Ferry: A Civil War Newsman at Harper’s Ferry (Shippensburg, 1987), 166; Henry Albert Potter to “Dear Father,” January 4, 1864, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan (henceforth BHL).

3. Robert S. Robertson to “Dear Parents,” January 19, 1864, Bound Volume 219-01, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park (cited hereafter as FSNMP); Henry O. Nightingale Diary, January 19, 20, 22, 29, 1864, University of California at Merced; Richard C. Bridges to “Dear Sister,” January 30, 1864, University of Mississippi (hereafter UM); Charles M. Walsh Diary, January 10, 1864, Box 119, Civil War Documents Collection, U.S. Army History and Education Center (hereafter cited as AHEC); Thornton Sexton to “Dear Father,” January 11, 1864, and Edgar Smithwick to “My Dear Mother,” January 14, 1864, both Duke University.

4. Crenshaw Hall to “Dear Father,” January 11, 1864, Alabama Department of Archives and History (ADAH hereafter); Benjamin Rountree, “Letters from a Confederate Soldier,” Georgia Review, Vol. 18, no. 3 (Fall 1964): 282; William R. Snell, ed., Myra Inman: A Diary of the Civil War in East Tennessee (Macon, 2000), 239; Daniel R. Hundley Diary, January 1, 1864, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina (henceforth SHC); Robert C. Caldwell to Mag Caldwell, January 3, 1864, East Carolina University.

5. War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, 1880-1901), 32(1): 209, 226, 234–235, 237–238, 372–376. Hereafter cited as OR, all references to Series 1 unless otherwise stated.

6. OR, 32(2):279; William Westervelt Diary, February 6, 7, 1864, Box 121, Civil War Documents Collection, AHEC; Henry Fike Diary, February 8, 1864, State Historical Society of Missouri; Benjamin Hieronymus Diary, February 6, 1864, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library (hereafter ALPL).

7. Albert Underwood Diary, February 10, 1864, Indiana Historical Society; Homer Levings to “Dear Parents,” March 3, 1864, University of Wisconsin-River Falls; Olynthus B. Clark, Downing’s Civil War Diary (Des Moines, 1916), 167–168; Sarah Elizabeth Paige Ball to her mother, February 24, 1864, in the Mobile Daily Advertiser and Register, March 1, 1864; Chauncey E. Barton to “Dear Sister,” April 14, 1864, Library of Congress.

8. OR, 32(1):176-77, and 32(2):425, 426.

9. OR, 35(1):276, 278.

10. William Woodlin Diary, February 5, 1864, Gilder-Lehrman Collection, New-York Historical Society (hereafter NYHS); Milton Woodford to Julina Woodford, February 23, 1864, Connecticut Historical Society (hereafter CHS); John Appleton Journal, February 7, 1864, West Virginia University; Arch Fredric Blakey, Ann Smith Lainhart, and Winston Bryant Stephens Jr., eds., Rose Cottage Chronicles: Civil War Letters of the Bryant-Stephens Families of North Florida (Gainesville, 1998), 315–317; OR, 35(1):321-22, 324-26.

11. Charles Macreading Vincent, Your Affectionate Son: Civil War Diaries & Letters by a Soldier from Martha’s Vineyard (Martha’s Vineyard Museum, 2008), 129–132; Clotaire Gay Diary, February 8–12, 1864, Brown University; Lester L. Swift, “Captain Dana in Florida: A Narrative of the Seymour Expedition,” Civil War History, Vol. 11, no. 3 (September 1965): 248; John B. Gallison Diary, February 10, 1864, Massachusetts Historical Society.

12. OR, 35(1):281-86; U.S. Congress, Senate, 38th Congress, 1st Session Report No. 47, Florida Expedition, 6–7.

13. OR, 35(1):288; John Gallison Diary, February 20, 1864; Swift, “Captain Dana in Florida,” 249; Blakey, Lainhart, and Stephens, Rose Cottage Chronicles, 319.

14. OR, 35(1):331; Edmond H. Jones to his wife, February 17, 1864, Baylor University; William H. Smith Diary, February 14–18, 1864, Georgia Department of Archives and History (hereinafter GDAH); G.W. Hunnicutt Diary, February 13–17, 1864, Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park (hereafter cited as KMNBP); Blakey, Lainhart, and Stephens, Rose Cottage Chronicles, 319.

15. OR, 35(1):303-4, 310–312, 316, 343; Joseph Hawley to “Dear Father,” February 28, 1864, CHS; Hawley to Charles Warner, March 16, 1864, CHS; William Woodlin Diary, February 20, 1864, NYHS; Oliver W. Norton, Army Letters, 1861–1865 (Chicago, 1903), 198–202.

16. OR, 35(1):298, 302, 315; Norton, Army Letters, 199–200; Donald Yacavone, A Voice of Thunder: The Civil War Letters of George E. Stephens (Urbana, 1997), 296–297; Lorenzo Lyon to “Dear Father,” February 23, 1864, NYHS; G.W. Hunnicutt Diary, February 20, 1864, KMNBP; William Smith Diary, February 20, 1864, GDAH; Swift, “Captain Dana in Florida,” 250–251; Luther Milton Loper to “Dear Cousin,” March 14, 1864, New York State Military Museum.

17. OR, 35(1):353-54; Howard K. Beale, ed. The Diary of Gideon Welles, 3 vols. (New York, 1960), 1:531–532; Laura Lee Diary, March 3, 1864, William & Mary College; Gordon A. Cotton, ed., From the Pen of a She-Rebel: The Civil War Diary of Emilie Riley McKinley (Columbia, 2001), 70; William M. Cash and Lucy Somerville Howorth, eds., My Dear Nellie: The Civil War Letters of William L. Nugent to Eleanor Smith Nugent (Jackson, 1977), 160.

18. OR, 32(1):174–175, 181, 255, 267.

19. Affidavits of Mary A. Bacon and Mahala Walker, Claim No. 19104, Southern Claims Commission Barred and Disallowed Claims (M1407), NA; George E. Waring Jr., Whip and Spur (Boston, 1875), 112–114; OR, 32(2):431.

20. OR, 32(1):256–257, 291–292, 299–300, 352–353, 364, 32(2):787–788; Wayne Bradshaw, The Civil War Diary of William R. Dyer, a Member of Forrest’s Escort (Monteagle, TN, 2009), 37–38; [George E. Waring Jr.] “Account by a Participant,” in Frank Moore, ed., The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events (New York, 1861–1868), 8:490.

21. OR, 32(1):299–300, 349–350, 352–354, 364; Bradshaw, The Civil War Diary of William R. Dyer, 38; [Waring], “Account by a Participant,” 490.

22. William and Loretta Galbraith, eds., A Lost Heroine of the Confederacy: The Diaries and Letters of Belle Edmondson (Jackson, 1990), 86–87; Cotton, From the Pen of a She-Rebel, 69–70; Beth Gilbert Crabtree and James W. Patton, eds., Journal of a Secesh Lady: The Diary of Catherine Ann Devereux Edmondston (Raleigh, 1979): 534–535.

23. John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant (Carbondale, 1967-2008), 10:119–120; OR, 32(1):9–11, 32(2):423–426, 452–453, 462–465; Report of Absalom Baird, March 9, 1864, John M. Palmer Papers, ALPL; George D. Wise Diary, March 1, 1864, Morristown and Morris Township (NJ) Library (M&MT hereafter); James R. Riggs to “Dear Uncle,” March 19, 1864, ADAH; Daniel Hundley Diary, February 23, 25, 26, 1864, SHC; Daniel Weaver to “Dear Sister,” March 3, 1864, ADAH.

24. OR, 33:143–148, 521–522; John B. Jones, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital (Philadelphia, 1866), 2:144.

25. OR, 33:172–173; John Rising Morey Diary, February 28-March 2, 1864, BHL; William G. Hills Diary, February 27-March 2, 1864, Library of Congress; Darwin Babbitt Diary, February 28-March 1, 1864, Michigan History Center (MHC).

26. Darwin Babbitt Diary, March 2, 3, 1864, and Babbitt to “Dear Parents,” March 9, 1864, MHC; William Heermance to Susie Leeds, March 14, 1864, Bound Volume 487-1, FSNMP; Allan Nevins, ed., A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, 1861–1865 (New York, 1962), 324; Henry Sparks Diary, March 5, 1864, Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, IN; David W. Lowe, ed., Meade’s Army: The Private Notebooks of Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman (Kent, 2007), 106, 107.

27. OR, 26(2):465, 34(1):167–168.

28. Sidney Robinson to “Dear Bro Will,” March 22, April 13, 1864, ALPL; Norman D. Brown, ed., Journey to Pleasant Hill: The Civil War Letters of Captain Elijah Petty, Walker’s Texas Division CSA (San Antonio, 1982), 373–387; John Watkins to “My Dear Irene,” April 10, 1864, Texas History Museum, Hillsboro; William B. Jordan Jr., ed., The Civil War Journals of John Mead Gould, 1861–1866 (Baltimore, 1997), 311–327; Beverly Hayes Kallgren and James L. Crouthamel, eds., “Dear Friend Anna”: The Civil War Letters of a Common Soldier from Maine (Orono, 1992), 83–87; Rebecca W. Smith and Marion Mullins, eds., “The Diary of H.C. Medford, Confederate Soldier, II,” The Southern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 34, no. 3 (January, 1931): 214–219.

29. Michael E. Banasik, ed., Serving With Honor: The Diary of Captain Ethan Allen Pinnell of the Eighth Missouri Infantry (Confederate) (Iowa City, 1999), 152–154; Henry Brockman Journal, April 9, 1864, Arkansas State Archives; Smith and Mullins, “The Diary of H.C. Medford,” 221; Jordan, The Civil War Journals of John Mead Gould, 327; Henry Fike to “Dear Cimbaline,” April 12, 1864, Kansas University; Sidney Robinson to “Dear Bro Will,” April 13, 1864, ALPL; Edmund Miles to “My Dear Elizabeth,” April 13, 1864, Massachusetts Historical Society.

30. OR, 32(1):502–507, 607–609; Robert K. Huch, ed., “The Civil War Letters of Herbert Saunders,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 69, no. 1 (January 1971): 20–23; Achilles Clark to “Dear Sisters,” April 14, 1864, Box 8, folder 19, Confederate Collection, Tennessee State Library and Archives.

31. OR, 33:295-301; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (Washington, D.C., 1894–1927), 9:640, 641, 645–646, 657.

32. OR, 34(1):661–671; John Reed to “Dear Father Mother and Sisters,” May 4, 1864, and Charles Pidcocke to “Dear Bobby,” May 15, 1864, both Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Little Rock; William Braly to Amanda Braly, May 7, 1864, and Milton Chambers to “Dear Brother,” May 8, 1864, both University of Arkansas; Banasik, Serving with Honor, 159–160; Mark K. Christ, ed. “This Day We Marched Again”: A Union Soldier’s Account of War in Arkansas and the Trans-Mississippi (Little Rock, 2014), 118–120.

33. Memorandum of August 23, 1864, Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress; Gideon Welles, “The Opposition to Lincoln in 1864,” Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 61, No. 3 (March, 1878): 367.

Related topics: Confederacy, strategy