Matt Capowski

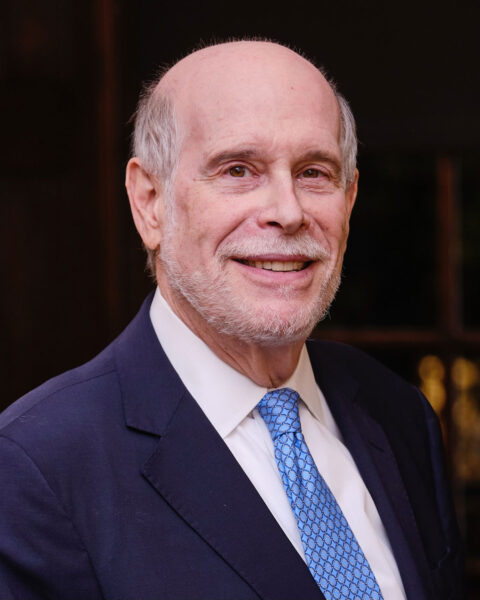

Matt CapowskiAuthor Harold Holzer

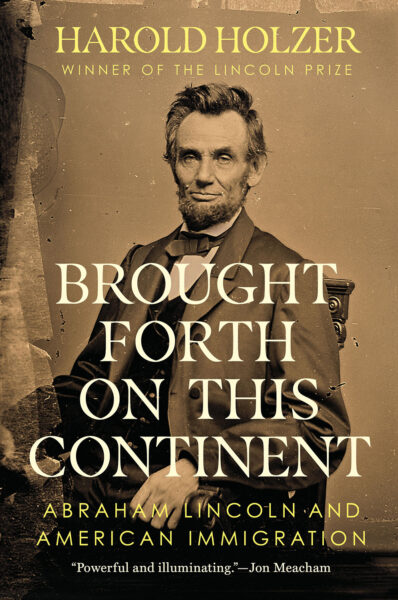

Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer is the author, co-author, or editor of more than 50 books. His latest, Brought Forth on This Continent: Abraham Lincoln and American Immigration (Dutton) came out in February. We recently interviewed Holzer to learn more about the book, how he came to its subject, and what he’s learned about the 16th president.

Over the years, you’ve examined Lincoln’s life, his political career, his ability as an orator, his performance as commander in chief, his attitudes toward slavery and emancipation, and his relationship with the press. When and why did you decide to write about him vis-à-vis the politics of antebellum and wartime immigration?

I contracted to do this book seven long years ago, believing the subject had been neglected; that immigration would become a big political issue in 2020 (it did); and that voters (and candidates) could benefit from Lincolnian context. Then I sidetracked into another project, The Presidents vs. the Press, which seemed equally relevant to current events. I always intended to return to immigration. For better or worse, the subject seems more relevant (and divisive) than ever. As the grandson of immigrants, I’ve long been fascinated by the topics of assimilation and identity, rights and restrictions, as they relate to my history and the country’s.

As you write in Brought Forth on This Continent, some 10 million immigrants settled in the U.S. in the three decades before the Civil War—having a profound cultural and political impact on the country. How did Lincoln view the changes wrought by immigration—and respond to them as a politician?

Lincoln’s emotional response was always empathetic; his political response evolved over time. His original “home,” the Whig Party, did not encourage immigration and naturalization, which explains why so many Irish migrants of the 1840s and ’50s migrated to the Democrats. Lincoln quickly comprehended that the nation and its population were changing rapidly and inexorably, and began forging alliances with immigrants sympathetic to antislavery, mainly Germans. That did not mean he stopped flirting with nativists who opposed Catholic immigration; as Lincoln once put it, he was willing to “fuse” with anybody to expand his own political tent, and this got him into occasional hot water. Yet by 1858, he insisted that the promise of the Declaration of Independence extended not only to ancestors of the founding generation, but to first-generation, foreign-born Americans as well. The Republicans had broadened their base as Lincoln had expanded his vision.

What were Lincoln’s strategies in gaining and retaining immigrant support for the war effort? What do you see as his greatest successes and failures there?

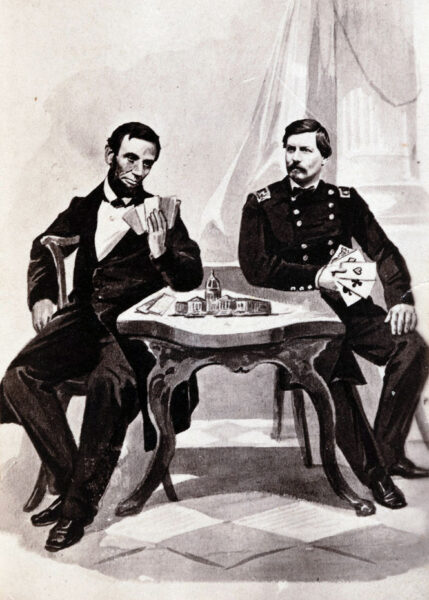

His overall strategy was of course to save the Union by any means necessary and available, and he perceived immediately that recruiting efforts should not be limited to Republicans or the native born. He encouraged both Germans and Irishmen to raise regiments, and before long, it might be said, the federal armed forces spoke with a foreign accent. Without doubt, Lincoln’s greatest success was universalizing the Union war, maximizing participation, and inspiring patriotism—by extending the American dream. This included naming immigrants to patronage and diplomatic posts. I suppose his major failures involved misplaced faith in foreign-born officers who proved less than capable in the field, like Irishman James Shields and German Franz Sigel—though both did galvanize ethnic recruitment. One more error: the original “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight” Conscription Act, which infuriated the Irish and ignited the 1863 Draft Riots.

How would you describe your research process? What sources did you find particularly illuminating?

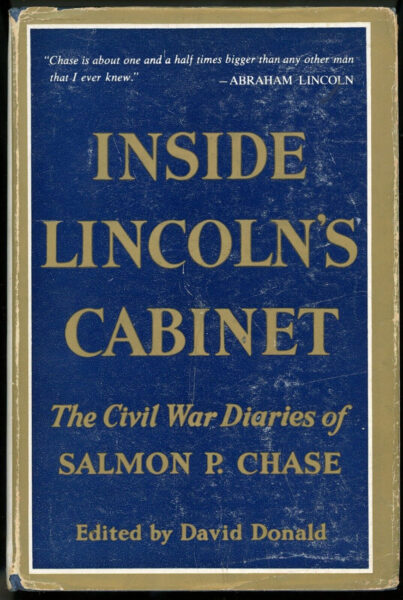

I have been writing books for four decades, but this is the first I’ve researched primarily online. Digitized resources have transformed the process. I turned first, as always, to Lincoln’s incoming and outgoing correspondence, then to period newspapers, diaries, regimental histories, and memoirs. I profited enormously from reading the anti-Catholic Know Nothing screeds of 1856, and the early anti-immigrant rants of unexpectedly bigoted nativists like Samuel Morse. There’s nothing like comparing the wartime coverage of opposing newspapers like The New York Times and World, or the Chicago Times and Tribune for news, context, and opinion. The ethnic press of course proved invaluable. I said at the outset that there’s scant literature on this topic, but I want to acknowledge historian Jason Silverman’s groundbreaking introductory work for Southern Illinois University Press’ “Concise Lincoln” series. I also found journal articles going back half a century, featuring major historians approaching many different aspects of the story. Finally, as always for me, there was much to find in the illustrated press—dependably great images along with unexpectedly shrewd analysis.

What if anything new did you learn about Lincoln?

Much of this story struck me as new, and I hope will strike readers the same way. As Lincoln expressed it, he wanted nothing less than to attract “replenishing streams” of foreign settlers to America. This breathtaking notion hasn’t been fully appreciated and analyzed. Securing borders meant little to him. Let me offer a “top four” list. First: Lincoln went so far as to propose that the U.S. finance the ocean passages of new immigrants during the military and civilian manpower shortages of 1863 and 1864. Second: Lincoln was almost paranoid about alleged illegal voting by unnaturalized Irishmen in the 1850s, and the extent of his schemes to deter such fraud astonished me. Third: Lincoln always favored a reasonably open door to America and an easy pathway for citizenship, earlier than I’d thought, and more strongly than I’d believed. Fourth: He never lost his taste for Irish jokes—what can one say? Above all, it was illuminating to learn how deftly Lincoln navigated roiling political waters to address national as well as immigrant concerns (not to mention foreign policy fallout). Lincoln wanted to export democracy and import small-D democrats, and he effectively pursued that dream.

Can you sum up in a sentence what you hope readers will take away from reading Brought Forth on This Continent?

Preserving the Union and ending slavery remained the principal goals of Lincoln’s presidency, but he simultaneously stood up to bigots by championing immigration and diversifying the nation (while admittedly supporting African-American emigration and Native American containment at the same time). That’s a long sentence (one of my bad habits), but it’s high time we understood Lincoln’s complex and consequential path to leadership on this vital issue.

What’s next for you? Any projects to share?

First, I plan to do a great deal of traveling to discuss the book. I’m always working on the next iteration of The Lincoln Forum—number 29 coming later in 2024. And I’m teaching a master’s course on Lincoln and immigration for the Gilder Lehrman Institute. The one big project I have in mind—I’ve been collecting material since the 1980s—is one I call “Lincoln From Life.” It would be a perfect bookend to my very first project, The Lincoln Image (1984). This time, I’d focus not on what the commercial picture industry did to portray Lincoln, but what Lincoln himself contributed by consenting, even in the busiest of times, to pose for painters and sculptors. Why did he do so? Of equal importance: Will publishers still take on a lavishly illustrated book? I guess I’ll find out.

Related topics: Abraham Lincoln