Library of Congress

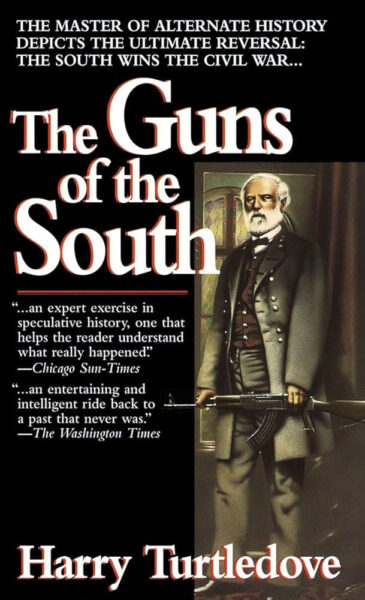

Library of CongressRobert E. Lee observes the Battle of Fredericksburg from a distance in this chromolithograph by Henry Alexander Ogden. In Harry Turtledove’s novel The Guns of the South, Lee’s prowess as a battlefield commander is supercharged by access to AK-47s.

Mississippian William Faulkner knew what he was talking about when he wrote, “For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863….” Indeed, southerners of all ages have enjoyed reimagining the Civil War since before it even ended. What if the Trent Affair had pulled Her Majesty’s Royal Navy into an alliance with the Confederacy? What if Stonewall Jackson had survived Chancellorsville and returned to corps command? And, maybe the granddaddy of them all: What if General Robert E. Lee had not gone through with the Pickett-Pettigrew Assault on day three at Gettysburg? These counterfactual scenarios are captivating because they seem entirely plausible and, for past generations, offered an alternative—even if only phantasmic—path to victory.

No one ever imagined what might have been if a group of radical, time-traveling Afrikaners from the year 2014 arrived in 1864 with crates of AK-47s for the fading Army of Northern Virginia. No one until Harry Turtledove’s 1992 novel, The Guns of the South.

The story (spoiler alert!) revolves around the interactions of General Lee and a group of South Africans led by one Andries Roodie. Calling themselves the “AWB” (Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging translates to Afrikaner Resistance Movement), Roodie and his comrades randomly appear in an Army of Northern Virginia camp with an Avtomat Kalashnikova. Known in modern times as the AK-47, it stuns the Confederates. Its rate of fire and magazine capacity are unlike anything that exists. The Confederates are overjoyed when Roodie offers to supply Lee’s men with thousands of AK-47s and copious stores of ammunition. Almost immediately, their fortunes on the battlefield begin to change.

In spite of his army’s newfound success, Lee becomes increasingly suspicious of how Roodie produces the AK-47s and metallic cartridges. Under pressure from the general, Roodie confesses that he and his men are from the future. According to Roodie, 2014 is a nightmare. The world is dominated by chaos, instability, and racial strife. Lee and his men are horrified to learn that non-whites have completely taken over and subjugated the white race. To help redeem his previous deception, Roodie reveals that the next major battle of this war will happen at “The Wilderness.” Now armed with assault rifles and historical knowledge from the future, Lee wins a mammoth victory. Propelled by their success at the Wilderness, Confederate forces capture Washington, D.C., and take President Abraham Lincoln hostage.

With both the United States capital and the president firmly in hand, Lee is able to negotiate an end to the war. The Confederacy achieves its independence, foreign nations line up to recognize the new Confederate sovereignty, and the institution of slavery appears to have a solid future. Then Lee shocks everyone. He wins the Confederate presidential election of 1868 on an anti-slavery platform. Roodie and other white supremacists are horrified.

Over the course of the novel—thanks in no small measure to Roodie’s own cruelty toward black POWs—Lee has come to see slavery’s inherent evils. He plans to gradually phase it out of Confederate society through new laws and a sort of buyout program. The AWB, however, is unwilling to accept that Confederate victory actually means the end of slavery and botches an attempt on Lee’s life. Outraged by the failed assassination scheme, Confederate forces storm AWB headquarters and discover that Roodie had lied about everything: The white race in 2014 was still firmly in charge of world affairs. Roodie had hoped changing the course of Confederate history would give South Africa a white supremacist ally in the future. Before the book ends, the time machine is destroyed, Roodie is killed by one of his slaves, and Lee follows through on his plan for gradual emancipation legislation.

The Guns of the South by Harry Turtledove

On the one hand, time-traveling white supremacists gave unexpected new meaning to another popular Faulkner quote, “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.” On the other hand, the plot of Turtledove’s novel isn’t all that out of sync with other pro-Confederate “reimaginings” from the 1990s—especially concerning Lee’s connection to slavery, slavery as the root cause of the war, and Confederate military capabilities. Two years before the release of The Guns of the South, Ken Burns’ televised documentary The Civil War took American living rooms by storm. The nine episodes prompted a resurgent interest in all things Civil War and made an overnight celebrity of writer and amateur historian Shelby Foote.

To the chagrin of academic historians, many of Foote’s most notable commentaries in The Civil War were firmly rooted in Lost Cause lore. In one segment, he argues that secession and the war had not, in fact, been about slavery, but rather was a simple case of leaders in the North and the South “fail[ing] to compromise.” In another, Foote opines that the Confederate military had never really been capable of winning the conflict because the Union waged war “with one hand behind its back.” And he claims that Lee was a caring, paternal, even regretful owner of slaves while depicting both Lee and Nathan Bedford Forrest—of Fort Pillow black massacre infamy—as chivalrous, Christian gentlemen. One year after the release of The Guns of the South, the 1993 made-for-TV movie Gettysburg starred Martin Sheen as Lee and reinforced the image of a noble, gentle, honorable soldier more or less detached entirely from slavery.

The Guns of the South is not unique in mirroring Lost Cause themes. What sets Turtledove’s work apart is how it reexamines Lee’s and the Confederacy’s connection to slavery through an international lens. The inclusion of Roodie and his white supremacist Afrikaners made sense in 1992. When the book was released, South Africa’s decades-old apartheid regime was crumbling. Since 1948, the system had segregated everything from stores, churches, and schools to elections, marriages, and employment opportunities. In 1994, the system was abolished. Nelson Mandela, who had been held for decades as a political prisoner, assumed the presidency of South Africa in May of that year and the western world celebrated the occasion as a new birth of freedom for all black South Africans.

This historic moment—and the near-universal condemnation of both apartheid and the men clinging to it—offered Turtledove a perfect opportunity to whitewash those aforementioned connections of Lee and the Confederate cause to slavery. Turtledove, who was dubbed “The Master of Alternate History” by Publisher’s Weekly, made the most of it. The lying Roodie and his men become foils to the honest, heroic Lee, who is leading a gallant but outgunned and outmanned war effort; the blatant cruelty of the South Africans’ racism is offset, first, by Lee’s respect for black Union soldiers captured in battle and then by his abrupt moral turn against the institution of slavery. Put another way, the South Africans in The Guns of the South became bogeymen made of straw. They gave proponents of Lost Cause lore someone to point at and say, “The Confederates weren’t nearly as bad as those guys!”

So what is to be said of The Guns of the South?

It’s easy to dismiss the book as clever science fiction rooted in what were then current international events. That would be a mistake. At minimum, it’s a time capsule illustrative of how we re-remember the Civil War through events and opinions in the present. Yet we may consider that the men who drove secession and started the war to protect slavery thought precisely as the AWB characters do in the novel. And when we remember that Confederate commanders like Lee and Forrest did things in real life (and worse) that make the fictional Roodie such a reprehensible villain, Turtledove’s book becomes something neither science nor fiction but an exercise in Lost Cause escapism beyond anything Faulkner could have dreamed.

Matthew Christopher Hulbert is Elliott Associate Professor of History at Hampden-Sydney College. An expert on the Civil War in the West, guerrilla violence, and film history, he is the author or editor of five books. His most recent is a biography, Oracle of Lost Causes: John Newman Edwards and his Never-Ending Civil War (Bison, 2023), which was a 2024 Spur Award Finalist.

Related topics: Robert E. Lee