Harper's Weekly

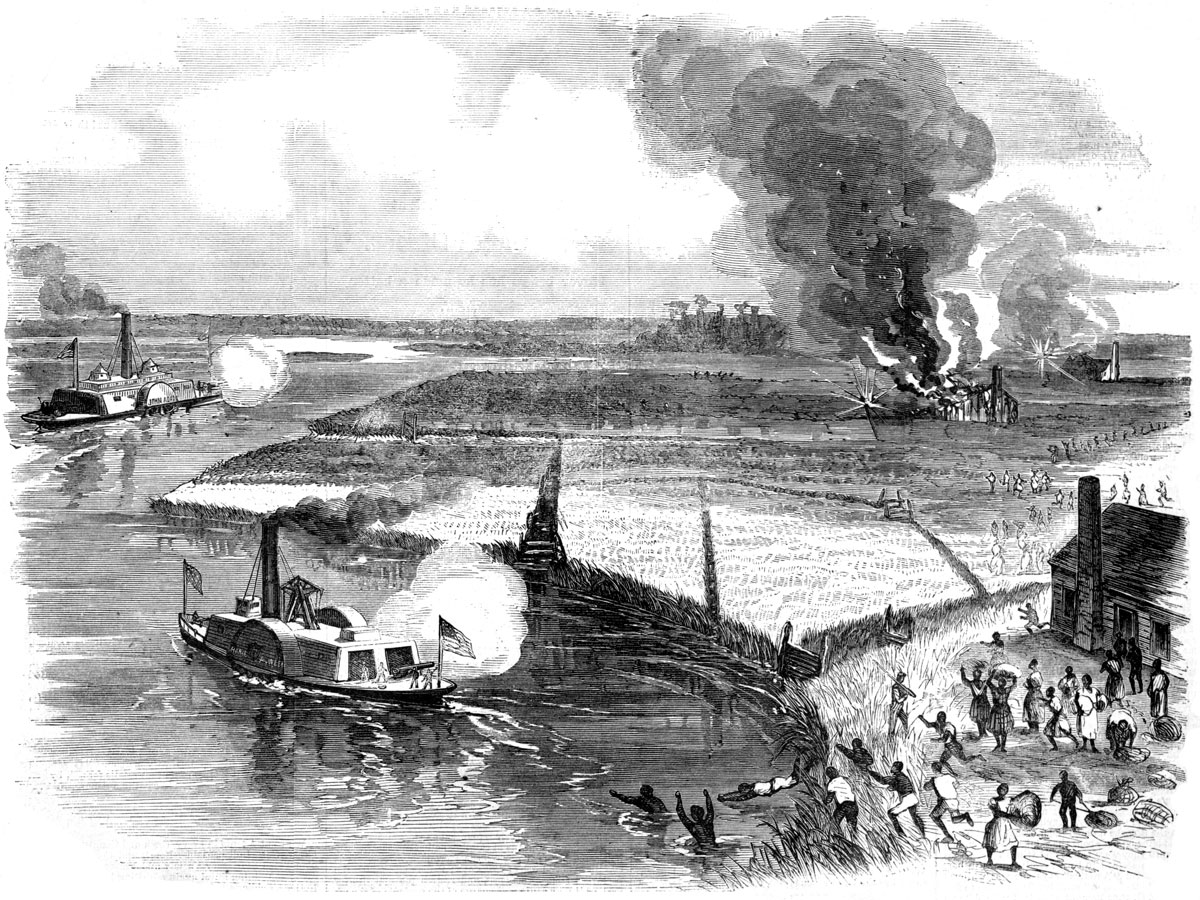

Harper's WeeklyA Harper’s Weekly illustration of the Combahee River Raid depicts slaves escaping to Union ships as plantation buildings burn in the distance.

Darkness had fallen on Beaufort when three Union army boats left the wharf around 9 p.m. on June 1, 1863, and steamed toward the Combahee River. The South Carolina Lowcountry was one of the South’s breadbaskets, where from cypress swamps over a hundred years before, slaves had carved tidal rice fields that in wartime the Confederacy was using to provision its civilians and military and also was exporting despite the Union navy’s blockade. At its southeast end, the 40-mile-long Combahee River flowed into St. Helena Sound, which Union forces had captured, along with Fort Walker on Hilton Head Island and Fort Beauregard on St. Phillips Island, in the Battle of Port Royal on November 7, 1861.

In that battle, at the sight of the Union navy’s armada of 40 ships, local slaveholders had fled, mostly to the mainland (a move remembered as the “Great Skedaddle”), as the Union army occupied Beaufort, Port Royal, and the Sea Islands. Some 8,000 enslaved people were freed, inaugurating the Port Royal Experiment, which invited the arrival of hundreds of northern abolitionist volunteers to open schools and stores, minister to, and manage the labor of the people who had been enslaved on Sea Island cotton plantations. It also set in motion social and economic changes that would lead the Union army almost two years later to undertake the daring Combahee River Raid, its objectives being to remove torpedoes from the river, seize supplies from area plantations before laying waste to them—and encourage recruits among adult male slaves freed by the raid.

Aboard the three army boats were Colonel James Montgomery, 300 men of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry, a regiment of black soldiers, Captain Charles Brayton, one battery of the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, and Harriet Tubman with her ring of spies, scouts, and pilots. Montgomery, the commanding officer, was an abolitionist who in the Bleeding Kansas era before the war had raised a company of free-soil “Jayhawkers” to confront pro-slavery settlers in the new territory. He received his commission as colonel in January 1863 and arrived in Beaufort in late February with 150 soldiers he had recruited in Key West, Florida, men who would form the nucleus of the 2nd South Carolina, among the first black army regiments raised. Montgomery recruited the remainder of the regiment’s first six companies in Beaufort from among the formerly enslaved men who had liberated themselves after the “Great Skedaddle.”

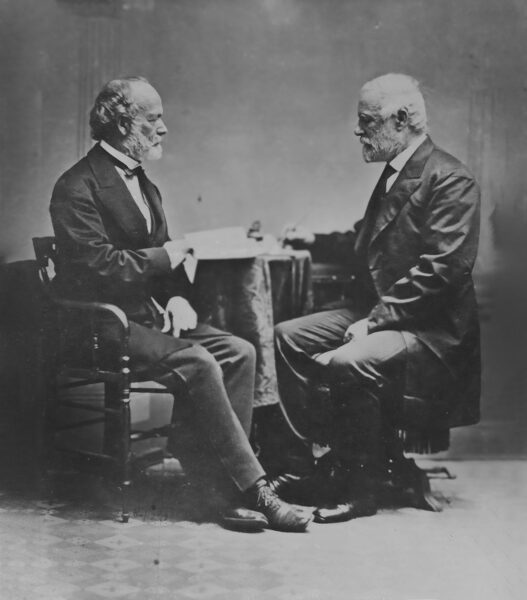

Kansas Historical Society (Montgomery); Library of Congress (Gillmore)

Kansas Historical Society (Montgomery); Library of Congress (Gillmore)James Montgomery (left) and Quincy A. Gillmore

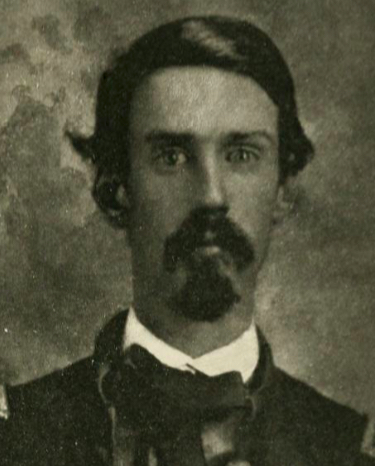

Tubman had arrived in Beaufort in May 1862 during the Port Royal Experiment, but not as a volunteer teacher, missionary, or labor superintendent.1 She was sent by Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts to serve as a spy and scout for the Union army, attached to the Beaufort headquarters of Brigadier General Isaac Ingalls Stevens. Tubman was the most famous conductor on the Underground Railroad; she had liberated herself, made approximately 13 trips back into the land of bondage to rescue approximately 70 people, and gave detailed instructions to approximately 70 others who successfully escaped slavery. (Later she became an active suffragist in New York State.)

So little was known about Tubman’s service because it was not documented in the military record during the war, though Union officers like Montgomery wrote letters attesting to her work and value as a scout to General Quincy A. Gillmore, the new commander of the Department of the South, and after the war in support of her applications for a military pension to compensate her for her military service.2 More about Tubman’s wartime activities came in the letters of northern volunteers in South Carolina for the Port Royal Experiment. She worked in the refugee camps in downtown Beaufort with people who liberated themselves by fleeing Confederate-controlled territory and finding safety behind Union lines. Tubman “made it a business to see all contrabands escaping from the rebels and is enable [sic] to get more intelligence from them than anyone else,” Lieutenant George Garrison (son of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison) wrote home to his brother in 1864.3 Tubman was also “commander of several men (eight or nine),” all spies, scouts, and pilots, according to a postwar affidavit for her application for a federal Civil War pension.4

"Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman" (1869)

"Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman" (1869)Harriet Tubman, a famous conductor on the Underground Railroad before the war, was instrumental in helping plan and guide the Combahee River Raid. This postwar illustration depicts Tubman as she appeared during the conflict.

After the Battle of Port Royal, the planters on the lower Combahee River had acted as aides de camp to Confederate forces in the area and donated their slaves’ labor to obstruct the Combahee River and keep the Union military from reaching their rice plantations. Days before the raid, Francis Izard, a shoemaker and farrier who liberated himself, informed Union officials that the Confederate army had “taken the guns away so now have a picket only there” at Combahee Ferry, across from Newport Plantation, where Izard had been enslaved. And at Combahee Ferry, they had two torpedoes in “tin or iron cans,” which were “about as big as [a] stove.”5 According to Tubman’s great-nephew Harkless Bowley, at some point before the raid Tubman’s men “found the men who had helped placed torpedoes in Combahee River to keep the Union boats from ascending.” They “brought them to the spot where she [Tubman] was landed and many women and children the men with the officers went up the river and took the torpedoes up.” They succeeded in “opening up the river for the union boats to ascend and cut off the suplies of the Rebel Armies.”6

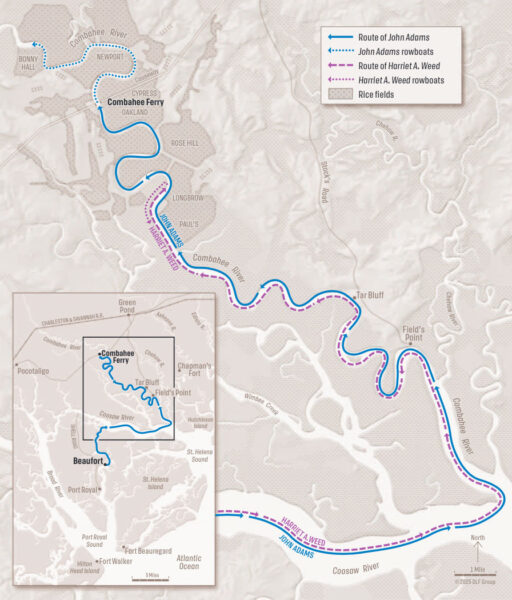

So under a full moon that June night, the Union boats left the wharf and proceeded up the Beaufort River, headed for the wealthy rice plantations under Confederate protection. After clearing the mouth of the Beaufort, they continued northward to the mouth of the Coosaw River. The Coosaw was known to be lined with sandbars that would have been indistinguishable even in full moonlight. The highest tidal amplitudes of the lunar cycle could not prevent one of the boats, USS Sentinel (a 350-ton screw steamer outfitted with one 30-pound Parrott gun and two rifled 12-pound field pieces), from running aground at the mouth of the Coosaw.7 The steamer could not be dislodged, nor could the expedition wait for the next high tide to attempt easier dislodgement. Soldiers were transferred to the two remaining ships—John Adams and Harriet A. Weed—but the loss of one of the steamers meant the expedition would have the capacity to convey only half as many people to freedom.

Once the soldiers were on board, John Adams and Harriet A. Weed continued upstream, navigating the interior of the Combahee’s wide bends, avoiding the edges where sand collected. John Adams, a 470-ton, 145-foot-long “old East Boston ferry boat,” drew only seven feet of water, was double-ended, and had two pilot houses, each of which looked each way. It had been armed with a 30-pound Parrott gun, two 10-pound Parrott guns, and an 8-inch howitzer.8 Its guns were small relative to the 32- and 64-pound guns wielded by the U.S. Navy at Port Royal—but they were larger and more powerful than weapons possessed by the Confederates.

The boats glided 20 miles upstream with no Confederate opposition, then made first landfall at Field’s Point, which commanded the road to Ashepoo Village, 15 miles away and the nearest access to the Charleston and Savannah Railroad. Confederate pickets had constructed a battery at Field’s Point and remained stationed there during the rainy season. Montgomery left Captain Thomas N. Thompson and his Company D of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry to engage the pickets, who fled at the sight of Thompson’s black soldiers. They ran away quickly, the New South newspaper reported, “leaving their blankets warm to our forces.”9 Before fleeing to the safety of nearby woods, the pickets’ commander, Corporal H.H. Newton of the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, sent couriers on horseback to inform the 4th’s Lieutenant W.E. Hewitt, stationed 10 miles away at Chisolmville, that the enemy was present on the Combahee River.

The boats pushed two miles farther upriver to Tar Bluff, which commanded a second road leading to Ashepoo Village. Captain James M. Carver and his Company E of the 2nd South Carolina disembarked and remained here.

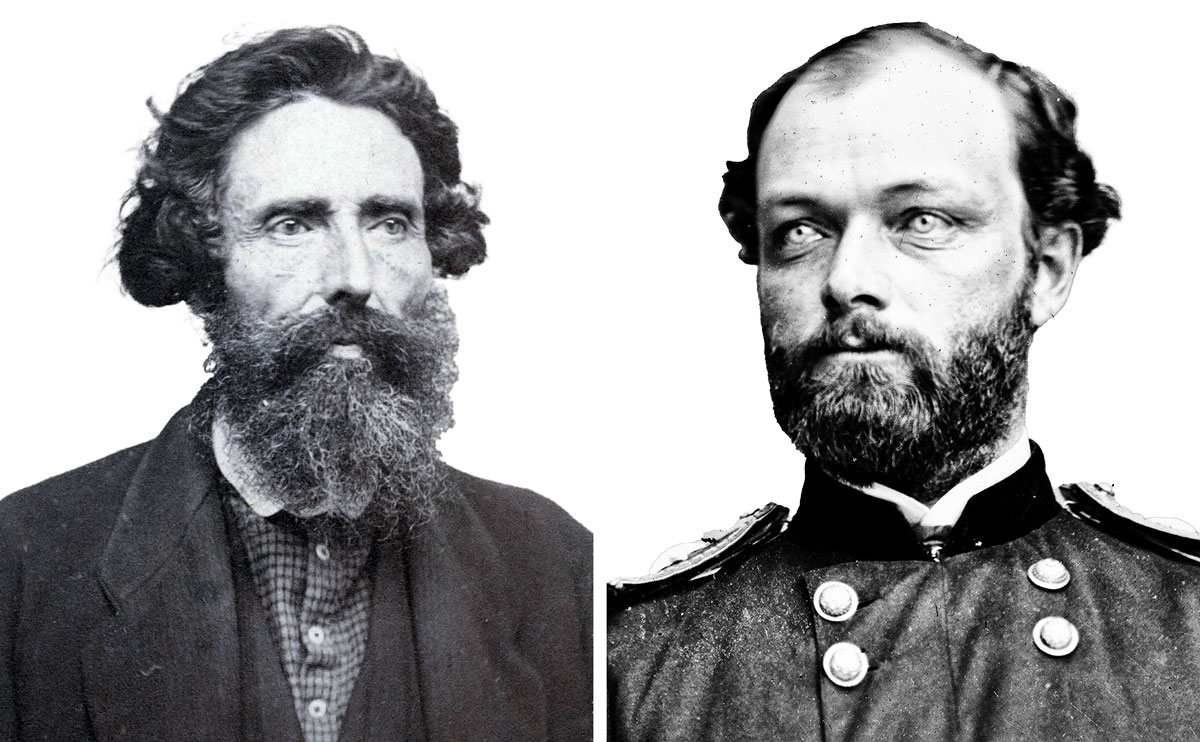

DLF Group

DLF GroupOn the evening of June 1, 1863, three army boats loaded with several hundred Union soldiers—and accompanied by Harriet Tubman and her ring of spies, scouts, and pilots departed from Beaufort, South Carolina, and steamed north toward the Combahee River, where they intended to remove river obstructions, seize supplies, destroy rice plantations, and encourage recruits among adult slaves freed in the process. After one of the ships (USS Sentinel) ran aground, the remaining two (John Adams and Harriet A. Weed) proceeded up the Combahee, landed troops at Field’s Point (who drove off Confederate pickets) and Tar Bluff, and headed toward Combahee Ferry. Both vessels dispatched troops in rowboats at different points on the river; these soldiers raided and burned plantation stores, skirmished with Confederate soldiers, and helped escort slaves (over 700 in all) back to the ships, which then returned to Beaufort.

Marshes continued to line one side of the Combahee River, but tidal rice fields abutted the other side. The boats had a clear passage and encountered the fields on James S. Paul’s plantation first. Captain William Lee Apthorp of the 2nd South Carolina later recalled how the rice fields were “well sprinkled with wooley heads hard at work.”10 It was not yet daybreak.

The next stop along the lower Combahee was Longbrow Plantation, where Joshua Nicholls, a widowed scholar and linguist, lived. Nicholls was in bed when his driver, an enslaved man, barged into his bedchamber about 5 a.m. and delivered news Nicholls was not prepared to hear.11 Harriet A. Weed, a 290-ton sidewheel steam transport, was coming up the river.12 It would subsequently turn into a creek in Nicholls’ rice fields and dock at the plantation’s boat landing.13

Nicholls told his driver to run, collect the enslaved field hands (who were already at work), and bring them to him. In the meantime, he would summon the house slaves, meet the driver with the field hands, and they would all go to the woods and hide until the Confederate army arrived to protect them.14 Troops never arrived to protect Longbrow. Instead, it was Major B. Ryder Corwin, commander of Harriet A. Weed, along with Captains Apthorp and John M. Adams and two companies of the 2nd South Carolina, who landed and proceeded to burn the threshed rice, stacked rice, steam-powered rice mill, and several rice barns, sending up thick clouds of smoke. And though the slaves professed their attachment to Nicholls, they returned to their quarters to gather their meager belongings. Then they went down to the river and boarded the transport steamer, freed people now. Nicholls was left to flee alone to the woods. From his hiding place, he could see smoke rising from his neighbors’ plantations.15

From the boat landing, Major Corwin sent rowboats to the Paul plantation. Minus Hamilton, 88, was likely to have been one of the “wooley heads hard at work” that Captain Apthorp described having seen a few hours earlier. Hamilton would later relate that the field hands were hoeing rice when they heard the approach of “Lincoln’s gunboats.” Then “ebry man drap dem hoe, and leff de rice;” they ran along the dikes (earthen embankments in the fields) to the Combahee. Their overseer sat on horseback on the dike. Like Nicholls, he told the field hands to run and hide, that the Yankees had come and would sell them to Cuba. But Hamilton and his fellow slaves did not feign attachment or obedience to the overseer. Every one of them ran for their lives and their freedom, straight to the waiting boats.16

Hamilton regretted he could not return to the slave quarters to retrieve the only things he called his own: two blankets. He and his wife, Hagar, had only the clothes on their backs—he wore a pair of pantaloons and Hagar wore a frock and head wrap. Hamilton was in awe of “de brack sojers so presumptious” as he called the men of the 2nd South Carolina. He was born enslaved and certainly could not imagine ever seeing black men in U.S. Army uniforms coming to liberate him. He could not believe his eyes as he watched them come ashore, holding their heads high, and then set fire to Paul’s rice barn (containing 10,000 bushels of rough rice from the previous year’s harvest) and plantation house. He said he “did n’t care nothin’ at all” seeing the entire plantation enterprise of the man who had held him and his family in bondage go up in flames.17 He did care about seizing the opportunity to liberate himself, his wife, his daughter, son-in-law, and 4- or 5-year-old granddaughter.18 He told a Union officer later, “I was gwine to de boat.”19

On Cypress Plantation, Colonel William C. Heyward of the 11th South Carolina Infantry, who had been commanding officer of Fort Walker in the Battle of Port Royal, was also unceremoniously awakened. The enslaved driver who was already in the lower rice fields supervising the field hands had sent word of the approach of an enemy gunboat. Heyward rushed outside to get his own view of the river. Looking through his spyglass, he saw John Adams coming slowly up the river, flying the U.S. flag, its deck crowded with people.20 Colonel Montgomery, Tubman, and her spies, scouts, and pilots were on this lead boat. Decades after the war, Tubman told one of her biographers that she had been “in de forwar’ boat whar de Colonel and Captain an de colored man dat was to tell us whar de torpedoes was.”21 John Adams’ twin pilot houses certainly provided an unobstructed view of the Combahee River. The vessel docked at Combahee Ferry and commanded the causeway, an earthen embankment formed between two tidal rice fields, leading from Cypress Plantation to a pontoon bridge.

J Henry Fair, 2015

J Henry Fair, 2015In the foreground of this aerial view are the rice fields at Newport Plantation. Colonel William C. Heyward was positioned near the sharp bend in the Combahee River shown here when he spotted John Adams coming upriver.

Heyward watched incredulously as a group of black soldiers took a small rowboat ashore onto his plantation. The soldiers walked back and forth over the causeway trying to attract the attention of any enslaved people by blowing a horn and waving a small flag. When the driver, himself an enslaved man, brought the field hands up from the lower rice fields to the Combahee River, Heyward told him to take them all to the woods and hide. (Joshua Nicholls had already fled alone to the woods about an hour earlier.) Heyward asked the driver if he had seen any Confederate pickets on the causeway; the man told Heyward he had not. Through his spyglass, Heyward could see all was quiet at the Combahee Ferry picket station, even though John Adams had come within a mile and a quarter of it.22 While Heyward, his driver, and the field hands stood on the riverbank, one of the field hands spotted four Confederate soldiers coming down the causeway. John Adams fired at them.

When one of the Confederates told Heyward that Yankee boats were on the river, it was the first report of enemy activity made by Confederates posted at the northern end of the river at Combahee Ferry. A picket would be court-martialed for making a false alarm, so the pickets at Combahee Ferry did not report the facts until they were absolutely certain.23 By the time Corporal Wesley D. Wall of 4th South Carolina Cavalry, Company F, sent a third courier to his regimental commander, Major William Pledger Emanuel, it was too late.

Heyward waited for a time and watched the Union force advance up the river and onto his and his neighbors’ plantations, then sent a courier on horseback to nearby Green Pond for reinforcements. When he learned that no Confederate couriers had been sent to where General William Stephen Walker, commanding officer of the Third Military District, was stationed, he rode to Green Pond himself.24

Around 7 a.m., Major Emanuel received news almost simultaneously from both ends of his command—Field’s Point at the southern end and Combahee Ferry at the northern end of the lower Combahee River. Corporal Newton’s two couriers arrived in Chisolmville hours after Captain Thompson and his soldiers had occupied the breastworks at Field’s Point. They delivered to Lieutenant Hewitt messages of enemy gunboats landing at Field’s Point and anchoring 100 yards from the pickets’ guard house. A second courier delivered Corporal Wall’s message that an enemy gunboat was heading up the Combahee River and was at the time positioned about half a mile from the pontoon bridge at Combahee Ferry. (The bridge, about 40 miles upriver from Beaufort, was one of the raid’s targets in disrupting Confederate transport in the area.)

Wall and his pickets did not fall back, as Newton’s pickets did at Field’s Point. He and his men crossed the long causeway on horseback under fire from John Adams. Then, the gunboat moved farther up to the pontoon bridge, landing more soldiers. Wall saw 25 to 30 more Union soldiers marching up and down the riverbank, waving the Stars and Stripes. He sent a third courier to Major Emanuel with the message that the enemy had landed at the pontoon bridge.

Colonel Montgomery’s force, though small, greatly outnumbered the Confederate pickets. After their initial encounter with Montgomery’s men, the Confederates focused on warning planters on the lower Combahee of the enemy’s presence and assisting them in evacuating and hiding their enslaved people in the woods before the “Abolition army” arrived.25

Wall sent pickets to Charles T. Lowndes’ Oakland Plantation and Heyward’s Cypress Plantation. Within an hour of Wall’s report reaching headquarters, Confederate reinforcements, including cavalry, had arrived at Cypress, while a second contingent of troops was on the move and a third occupied breastworks at the edge of a causeway. However, by then the Union raiders had been on the lower Combahee rice plantations for hours, removing and destroying property. Major Emanuel ordered Captain H. Godbold of the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, Company F, to Field’s Point; Captain Thomas Haynes Bomar of the Chestatee Light Artillery had positioned two artillery pieces on the road. Two additional pieces were ordered to Heyward’s plantation but never arrived.

Major Emanuel received inaccurate intelligence that the Union army’s boats had passed the pontoon bridge at Combahee Ferry and were heading to the Charleston and Savannah railroad bridge. Montgomery’s force had gone beyond the pontoon bridge, but turned back after they encountered obstructions in the river. They were not headed to the railroad; according to Colonel Montgomery’s report on the raid, their goal was burning the pontoon bridge and cutting Confederate supply lines.26 Major Emanuel ordered Bomar’s artillery, which might have been able to stop the enemy’s ascent up the river, to position itself to protect the railroad. Emanuel himself left his position and headed 14 or 15 miles to Salkehatchie to reinforce the Third Military District when General Walker and his forces were five or six miles away at Pocotaligo.

Meanwhile, the men of the 2nd South Carolina were bravely walking across the causeway, rice fields on both sides, onto Heyward’s plantation not knowing if they were heading into a Confederate ambush. Wall fired on them, but was outgunned. John Adams’ small guns were too much. The soldiers proceeded with their mission of destruction, torching all the buildings except for the slave quarters.

The soldiers of the 2nd South Carolina had all liberated themselves from enslavement a few months, if not weeks, before the Combahee raid. One of them, Friday Barrington, had escaped bondage on Cypress Plantation and headed to Beaufort, where he joined Colonel Montgomery and other recruits before the 2nd South Carolina was organized. In his escape, Barrington had left behind his parents, sister, and brother-in-law.27 He now returned with his Union army comrades to rescue his family and take them to U.S. protection in Beaufort. Barrington was probably not the only man to liberate himself before the raid, find safety in Beaufort, enlist in the 2nd South Carolina, and return as a soldier on the Combahee River Raid to liberate kin. But his is one story we know.

Gift of Erving and Joyce Wolf, in memory of Diane R. Wolf, 1982 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gift of Erving and Joyce Wolf, in memory of Diane R. Wolf, 1982 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art“On to Liberty,” an 1867 painting by German-born Union army veteran Theodor Kaufmann, depicts a group of enslaved women and children walking toward Union lines in search of freedom—a scene repeated on a larger scale, and under more precarious conditions, during the Combahee River Raid.

Years after the war, Peggy Moultrie Brown remembered, in her application for a federal widow’s pension, what happened at Cypress Plantation on the morning of June 2, 1863, where Colonel Heyward lived in “magnificent style” in a “mansion that equaled any” on the mainland.28 According to Brown, “the government boat came right up to the plantation landing on the Combahee River. We all, were then 100 of William C. Heyward’s slaves went onboard and were carried to Beaufort, South Carolina.” Confederate reinforcements in the form of a contingent of the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Peter Breeden, arrived in time to witness Heyward’s magnificent estate, rice mill, and storage bin filled with rice from the previous year’s harvest going up in flames and see black soldiers confiscating Heyward’s private property, including his prized white stallion—still saddled, bridled, and carrying his saber and pistols—several carriages, and additional horses. Breeden had divided his force, sending out skirmishers and going down the main road to take a position at the breastworks on the edge of the causeway while the 2nd South Carolina soldiers and the enslaved they had freed retired to John Adams. When Confederate sharpshooters opened fire at them, Captain Brayton “cut his swath broad and smooth” with John Adams’ guns.29 Breeden and his men retreated to the woods, which must have been crowded with slaveholders and retreating Confederate troops.

Another contingent of Breeden’s men went on horseback downriver toward Longbrow Plantation (the Nicholls residence), where Major Emanuel learned the second enemy vessel, Harriet A. Weed, had docked and disembarked a few dozen black soldiers. Breeden’s men encountered a Mr. Pipkin, overseer at Oakland Plantation, who requested their aid in stopping any enslaved people from getting to John Adams and going off to freedom. Three soldiers accompanied Pipkin back to Longbrow and positioned themselves near the barn. Pipkin came within 90 yards of a girl in flight and shot her dead. This unnamed child was the only casualty among the people freed that day. Pipkin and Breeden’s small force succeeded in preventing an untold number of escapes from Oakland Plantation.30

We don’t know if Tubman went up the east or west bank of the Combahee after John Adams commanded the causeway. She was certainly on one of the rowboats sent to Newport Plantation located across the bend in the river from Cypress on the east bank or to Bonny Hall Plantation on the west bank. We do know she was not only aboard John Adams, but also disembarked and went onto the plantations. Tubman told Emma P. Telford, her friend and interviewer in Auburn, New York, decades after the war that “the Colonel blowed the whistle and stopped the boat and a company of soldiers went ashore. Colonel Montgomery blew the whistle again … you could look over the rice fields, and see them coming from every direction.”31 (Telford wrote an unpublished manuscript about Tubman.) Great-nephew Bowley wrote that Tubman had “made her way to the cabins of the slaves, talked with them….”32 In a separate account, Tubman reportedly “got over to the main a few days ago she went to burning buildings and she helped bring away contrabands.”33 Leaving the plantations, Tubman helped a sick woman carry two pigs. Tubman also remembered what happened when the order was given to the soldiers to “double-quick”: “I started to run, stepped on my dress, it being rather long, and fell and tore it almost completely off.” When she got back aboard the boat, “there was hardly any thing left of it but shreds.”34

Across the lower Combahee River on the west bank, the overseer on Walter Blake’s Bonny Hall Plantation and three Confederate soldiers sicced “negro dogs”—canines used by slave patrols to hunt escapees during the antebellum period and by the Confederacy against black soldiers during the war—on the enslaved people joining with the Union troops.35 Those on Bonny Hall who turned back, and many others who had not arrived in time to board the Union boats, were left behind in bondage. They likely faced great brutality for trying to escape. The 3rd Rhode Island’s chaplain described “so many souls within sight of freedom, and yet unable to attain it” as “the saddest sight of the whole expedition.”36

By the time Confederate troops moved off to Combahee Ferry, John Adams had moved downriver. It traveled south to Oakland Plantation to prevent Lieutenant Breeden’s forces from coming between the enslaved people there and the rowboats. Then, John Adams cast off and joined Harriet A. Weed, picking up a few more people along the way and remaining in the lead. Major Emanuel had taken Pipkin on as his guide. Pipkin led Emanuel to Stock’s Road in pursuit of the 2nd South Carolina soldiers coming up the same road. Captains Godbold and Bomar were also in pursuit to reinforce Rebels at Tar Bluff. Emanuel and his men posted pickets around Oliver Middleton’s plantation and retreated to the dense woods. But by the time Confederate reinforcements arrived, Montgomery’s men had set fire to Middleton’s rice mill. John Adams picked up Captain Carver, who was standing on the edge of the bluff waving his hat (the signal that all was safe), and his men.

Harriet A. Weed continued downriver to Field’s Point, where Captain Thompson and his Company D had disembarked in the early morning. They had skirmished for hours with Confederate reinforcements. Thompson held off the Rebels by mounting half of his men on horses captured from surrounding plantations and sending them out as pickets and scouts. The pickets must have spotted Emanuel and Hewitt as they rode up Stock’s Road. Three Confederate infantry regiments, 100 cavalry, and a full battery of artillery arrived in Green Pond, then the cavalry marched down Stock’s Road to Field’s Point. Thompson’s black troops met them at the edge of the swamp in an ambush. They fired on the Confederate soldiers, forcing them to retreat into the woods. One Confederate soldier was killed in the firefight at Field’s Point. No Union soldiers were killed in the raid.

The boats had arrived at a critical juncture. After clearing out the Rebels, Thompson’s troops had almost exhausted their ammunition. At the same time, Emanuel’s men had regrouped and began driving Thompson’s men back when Harriet A. Weed arrived. John Adams brought up the rear and fired shells at the Confederate forces. Then the ships pushed off downriver.

Ordered back to Tar Bluff, Emanuel’s men subsequently took Stock’s Road down to Field’s Point to scour the woods. Lieutenant Breeden arrived at nearly 9 p.m. that night. John Adams and Harriet A. Weed were well on their way through the mouth of the Coosaw River and back to Beaufort.

Captain Apthorp determined that the Confederate army did not counterattack because of the “suddenness and audacity” of Colonel Montgomery’s men. Three hundred troops had duped the Confederates into taking them for a spearhead of the U.S. Army Department of the South. The Confederate commanders and soldiers were, according to Apthorp, completely “bewildered” and absolutely “stupefied.” Taken by surprise, they never mounted decisive action. By the time they did, the “mischief” to the tune of $6 million in private property damage was done. And the Union vessels were “out of their reach” carrying onboard 756 formerly enslaved men, women, and children, the lower Combahee planters’ most valuable assets.37

Edda L. Fields-Black is a professor in the Department of History and Director of the Humanities Center at Carnegie Mellon University. Her publications include COMBEE: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom during the Civil War (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Notes

1. “Unnamed Steamers Off Shore,” Charleston Mercury, May 30, 1862; Charles P. Wood, A History Concerning the Pension Claim of Harriet Tubman, 1868, Record Group 233: Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, 1789-2015, 1, National Archives, Washington, D.C. (hereafter NARA); “Harriet Tubman Request for Payment,” private collection (Harriet Tubman Home, Auburn, NY).

2. Wood, A History Concerning the Pension Claim of Harriet Tubman, 2-3.

3. Lt. George Garrison to William Lloyd Garrison II, February 10, 1864, Garrison Family Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA.

4. Accompanying Papers of the 55th Congress, Record Group 233, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, 1789-2015, NARA.

5. Francis Izard, January 1, 1863, U.S. Union Provost Marshal’s File of Papers Relating to Individual Civilians, 1861-1867, M345, Record Group 109, NARA.

6. Harkless Bowley to Earl Conrad, Augusts 6, 1839, Harriet Tubman Earl Conrad, Conrad/Tubman Collection, 1939-1940, Scholarly Resources, Wilmington, DE.

7. E. Kay Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels, Steam and Sail, Employed by the Union Army, 1861-1868 (Camden, ME, 1985), 291.

8. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “Up the St. Mary’s,” Atlantic Monthly 15, no. 90 (1865): 423, 25, 31; Higginson, “Up the St. John’s,” Atlantic Monthly 16, no. 95 (1865): 312; Higginson, Army Life in a Black Regiment and Other Writings (Boston, 1900), 88, 137, 232–233; Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops, Late 1st South Carolina Volunteers (Boston, 1902), 26-27; Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels, 177;

9. “The Expedition Up the Combahee,” The New South, June 6, 1863.

10. William Lee Apthorp, “Montgomery’s Raids in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina, 1864,” M89F, William Lee Apthorp, 34th USCT, Apthorp Family Papers, 1741-1964, HistoryMiami Museum, Miami, FL, 15-16.

11. “The Raid on Combahee,” The Mercury, June 19, 1863.

12. Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels, 144.

13. “The Raid on Combahee.”

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Christopher Looby, ed., The Complete Civil War Journal and Selected Letters of Thomas Wentworth Higginson (Chicago, 2000), 166; Higginson, Army Life in a Black Regiment, 237.

17. Looby, Letters of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 166-167; Higginson, Army Life in a Black Regiment, 237-238.

18. James Lowndes Estate Inventory, 1839, South Carolina Probate Records, Files and Loose Papers, 1732-1964, 1834-1844, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC; Edward Rutledge Lowndes Estate to Arthur Middleton Parker, Bill of Sale, March 10, 1853, South Carolina, Charleston District, Estate Inventories, 1732-1844, 1732-1744, South Carolina Department of Art and History, Columbia, SC; Binah Mack, December 28, 1872, United States, Freedman’s Bank Records, 1865-1874, NARA.

19. Looby, Letters of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 166-167; Higginson, Army Life in a Black Regiment, 237-239.

20. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C., 1880), Series 1, Volume XIV, 307–308 (hereafter OR; all subsequent references are to Series 1, Vol. XIV).

21. Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate (Army), “Civil War Court Martial File L15566, US v. Private John E. Webster,” Vo. G 47 Regiment Penn Vols, 28, RG 153, NARA; Emma P. Telford, Harriet: The Modern Moses of Heroism and Visions (Auburn, NY, 1905), 18.

22. OR, 307-308.

23. Ibid., 292.

24. Ibid., 307-308.

25. Denison, Shot and Shell, 156.

26. “The Combahee Expedition,” Philadelphia North American and United States Gazette, June 8, 1863; Denison, Shot and Shell, 155.

27. Dr. James Heyward to William C. Heyward, South Carolina, Charleston District, Bill of Sales of Negro Slaves, 1774-1872, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC; Robert (Phoebe) Frazier, U.S. Civil War Pension File, Record Group 15, NARA; Prince (Tyra) Polite, U.S. Civil War Pension File, Record Group 15, NARA; Friday Barrington, U.S. Civil War Pension File, Record Group 15, NARA; Edward (Catherine) Bennett, U.S. Civil War Pension File, Record Group 15, NARA; Jacob (Elvira) Campbell, U.S. Civil War Pension File, Record Group 15, NARA.

28. “The Expedition Up the Combahee.”

29. Denison, Shot and Shell, 156.

30. “The Enemy’s Raid on the Banks of the Combahee,” The Mercury, June 4, 1863; “The Expedition Up the Combahee”; “A Raid among the Rice Plantations,” Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1863; Apthorp, “Montgomery’s Raids in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina,” 17-18; OR, 293-295, 298-306.

31. Telford, Harriet, 9, 16-18; Sarah H. Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (Auburn, NY, 1869), 41-42; Sarah Bradford, Harriet Tubman: The Moses of Her People (1886; reprint, New York, 1901), 101.

32. Harkless Bowley to Earl Conrad, August 6, 1839, Earl Conrad, Conrad/Tubman Collection.

33. Harriet M. Buss, My Work Among the Freedmen: The Civil War and Reconstruction Letters of Harriet M. Buss, ed. Jonathan W. White and Lydia J. Davis, (Charlottesville, 2021), 20-21.

34. Frank Sanborn, “Harriet Tubman,” The Commonwealth Boston, July 17, 1863; Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, 40-41; Bradford, Harriet Tubman, 100–101; Telford, Harriet, 19-20.

35. OR, 298-306.

36. Denison, Shot and Shell, 155-57; OR, 298-306.

37. Apthorp, “Montgomery’s Raids in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina,” 16, 20.

Related topics: African Americans, emancipation, women