Wearing a black suit and pencil tie, a man strolls into the frame. With a Chesterfield cigarette smoldering between his fingers, he turns, squints at the camera, and breaks the fourth wall:

“Imagine, if you will, a country marking the hundred-year anniversary of a thwarted rebellion. Yet there is something highly irregular about this centennial celebration: The men who tried to destroy the nation have become heroes and the all-consuming political issue that necessitated the conflict has been intentionally forgotten.”

You assume the signpost up ahead will reveal your next stop is the twilight zone. But you’re wrong. The destination of tonight’s episode is the United States of America in the early 1960s.

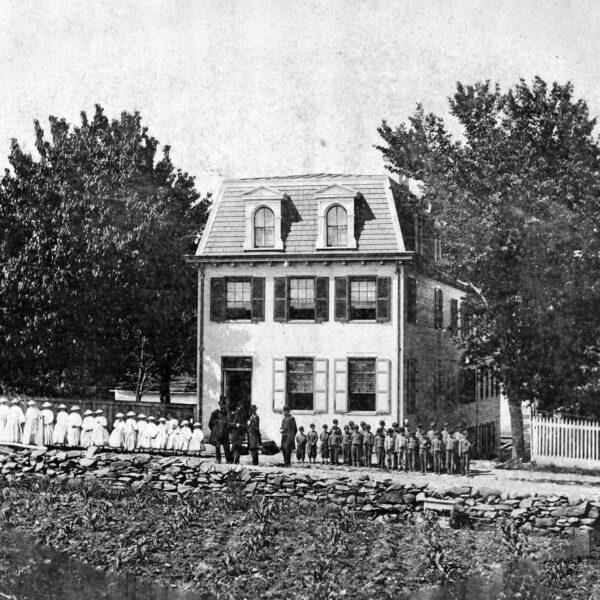

CBS/PhotoFest (Twilight Zone)

CBS/PhotoFest (Twilight Zone)Rod Serling’s television show The Twilight Zone used the Civil War as a backdrop several times in the 1960s. Shown here is a scene from “Still Valley” with actors Gary Merrill and Vaughn Taylor.

Rod Serling—the creator and iconic host of The Twilight Zone—never delivered such a narration, though he certainly could have. In the first half of the 1960s, Americans were indeed marking the hundred-year anniversary of a defeated rebellion. The Civil War had been triggered by the debate over slavery and the question of its expansion into the western territories. Fire-Eaters laid siege to Fort Sumter in 1861. The fighting raged for four long years, destroying untold property, claiming the souls of 750,000 men, and setting in motion the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in April 1865. A century later, the Centennial sparked renewed interest in the conflict. That spawned myriad television shows, movies, and books and prompted non-academics to join historical roundtables to talk about them. Americans flocked to battlefield parks and monuments. For better or worse, they also began creating new statues.

Yet more than just being the observance of an important event long past, the tenor of the Civil War Centennial revealed as much about the United States of the 1960s as it did about the country in the 1860s. Now, too, was a turbulent moment in the American experience. Resistance to Brown v. Board of Education was massive. The Cold War was seeming less and less cold; worry abounded that Soviet warheads might come cruising overhead at any moment. And a stunned citizenry lost another president to an assassin’s bullet. Informed in part by these overlapping crises, Americans collectively remembered the Civil War through a reconciliatory lens—a commemorative perspective that underscored white unity and American exceptionalism at a time when the nation seemed to want both badly. Therein, the Centennial version of the conflict was a brothers’ war, a contest waged by two civilized cultures that seemed to just temporarily misunderstand each other. Chivalrous men fought bravely for both sides. The institution of slavery—its spread or abolition—was inconsequential.

CBS/PhotoFest (Twilight Zone)

CBS/PhotoFest (Twilight Zone)Austin Green as President Abraham Lincoln in The Twilight Zone, “The Passersby.”

Into this political and cultural maelstrom came The Twilight Zone. To be fair, it was only one of a number of shows that cashed in on Civil War-themed teleplays in the early 1960s. Among them, Bonanza, Gunsmoke, The Americans, Johnny Shiloh, and The Andy Griffith Show did too. But The Twilight Zone wasn’t your average drama or soap opera or sitcom—and Rod Serling not your average showrunner. From its inception in 1959, the series featured exceptional writing, much of it by Serling, and routinely forced viewers to confront their own worst attributes and behaviors.

The show delivered stark warnings about antisemitism and bigotry (“Deaths-Head Revisited,” 1961); warmongering (“Judgment Night,” 1959; “The Shelter,” 1961), fascism and tyranny (“The Mirror,” 1961; “The Obsolete Man,” 1961; “He’s Alive,” 1963), and white supremacy (“I Am the Night—Color Me Black,” 1964). Whether it was race or politics or atrocities, seemingly no topic was off-limits. So, when mainstream Centennial celebrations ignored slavery and romanticized Confederates—which is to say, when they acquiesced to standard Lost Cause tropes—the situation seemed tailor-made for Serling and company to critique. But things were not always as they seemed in Serling’s fifth dimension.

The first of five Civil War-themed episodes of The Twilight Zone, which ran from 1959 to 1964, aired on March 18, 1960. “Long Live Walter Jameson,” starring Kevin McCarthy, told the story of a history professor who turns out to be 2,000 years old. What eventually outs Jameson as an immortal are his ultra-vivid descriptions of the Civil War, specifically his intimate—and as it turned out, firsthand—knowledge of William T. Sherman’s campaign in Georgia. “The Union soldiers burned Atlanta, but I assure you they took no pleasure in their work,” Jameson informs his students. “They were forced to it by a man they hated more than they could ever hate the rebels. An ugly, sullen, unbelievably brutal man named William Tecumseh Sherman.” According to Jameson, Sherman personally started the fires that ruined “that great citadel of grace and beauty.”

CBS/PhotoFest (Twilight Zone)

CBS/PhotoFest (Twilight Zone)Russell Johnson and John Lasell in The Twilight Zone, “Back There.”

Almost a year later, in January 1961, “Back There” began with members of an exclusive Washington, D.C., social club playing bridge and discussing time travel. Their get-together just happens to be on April 14, 1961. When an engineer named Peter Corrigan (played by Russell Johnson) leaves the club and steps into the street, he is transported to the same moment but in 1865. Corrigan desperately tries to warn the police, the military—anyone who will listen—that President Lincoln is going to be murdered. His efforts to save the president are stymied by none other than John Wilkes Booth in disguise. The camouflaged Booth (John Lasell), sporting the definition of a dastardly mustache, drugs Corrigan and holds him hostage while the assassination plot unfolds. Whereas “Long Live Walter Jameson” used Sherman as a foil to illustrate the grandeur of the Old South, “Back There” employed Booth’s monstrousness as the antithesis of Lincoln’s greatness.

In October 1961, the show rolled out its third Civil War plot in “The Passersby.” The episode featured an unnamed Confederate sergeant (played by James Gregory) who befriends a Confederate widow, Lavinia Godwin (Joanne Linville). They chat and reminisce amid the ruins of her burned-out plantation, all while zombie-like soldiers shuffle and limp down the road that passes her gate. A Federal lieutenant stops and asks for water from Godwin’s well. She wants to kill the Yankee, but the sergeant defends him; he recalls the lieutenant saving his life in battle. Then, more than a little perplexed, he remembers seeing the lieutenant die shortly thereafter. Gradually, it becomes apparent that Lavinia, the sergeant, the lieutenant, the throngs of passing soldiers, Union and Confederate, are all dead—and traveling together to the same place. Lavinia can’t seem to accept this reconciliation of spirits until Lincoln himself appears on the road, quoting from Julius Caesar, and gives her courage.

Just a few weeks after “The Passersby,” Serling introduced “Still Valley,” an episode set in 1863 and focused on Joseph Paradine (played by Gary Merrill), a grizzled Confederate sergeant. He admits that things are looking bleak for the Confederacy but still chews out a fellow scout for being a quitter. Going it alone, Paradine reconnoiters a small town and much to his surprise finds a company of Union troops frozen—actually frozen—in their tracks. Not only has a warlock disabled the Federals, but the menacing spellcaster gives Paradine the book of black magic that might freeze the entire Union army. Initially, Paradine is ecstatic; this magic might turn the tide of war for the outnumbered and outgunned Confederacy. Only when he starts to wield the magic does he realize the true cost of such power: “Satan,” he chants, “I call upon you, and in doing so I revoke the name of….” Paradine can’t do it. He won’t do it. Even in exchange for total victory, the diehard Confederate cannot bring himself to damn and dishonor his cause. “If this cause is to be buried,” he laments, “let it be put in hallowed ground.”

After four Twilight Zone episodes in two years set during the Civil War, which included “The Passersby” and “Still Valley” airing nearly back-to-back, audiences had to wait until February 1964 for the fifth—and final—one. In place of a standard teleplay, however, Serling screened a decorated French interpretation of Ambrose Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” The plot follows a condemned prisoner, Peyton Farquhar (played by Roger Jacquet). Not a proper Confederate soldier, he has earned a date with the hangman for fighting as an irregular in Virginia circa 1862. As Farquhar is hanged from the bridge spanning Owl Creek, the rope breaks and dumps him into the rushing water. He frantically avoids drowning, dodges gunfire, and eludes recapture for nearly the entire episode. Then, just as Farquhar and his wife are about to reunite on their idyllic plantation, the dream sequence ends. His body is left swinging from the bridge.

So what were audiences in the 1960s to make of the Civil War Centennial as observed in The Twilight Zone? On the one hand, the Old South was a genteel, wonderful place (that apparently included no slaves). Walter Jameson lectures about it, Lavinia Godwin reminds us of its former beauty, we see it when Peyton Farquhar dreams his way home. And if you can look past the treason and 750,000 dead, Confederates defending that Old South weren’t such bad guys after all. Their transgressions are nothing compared with a pyromaniac like Sherman or an assassin like Booth. The two sergeants featured in “The Passersby” and “Still Valley” are honest and honorable. Chivalrous to the last, Paradine would rather lose a Confederate nation than taint its good character with Lucifer’s influence. It’s almost impossible not to root for Confederate partisan Peyton Farquhar, not only to escape death, but to live happily ever after.

On the other hand, there is Abraham Lincoln. He is sectional reconciliation and American unity personified. During the concluding scene of “Back There,” Corrigan declares to his clubmates, “in the matter of time travel, gentlemen, some things can be changed, others can’t.” Somehow, Lincoln had to die to become imbued with the power to heal the nation’s wounds. In “The Passersby,” he all but says that. “You see my dear, I’m dead too,” Lincoln tells Lavinia. “I guess you might say … I’m the last casualty of the Civil War.” He then consoles her—a Rebel spirit, both literally and figuratively—and convinces her to move on from the war. This was why he had come down the road last: to make sure no one, blue or gray, was left behind.

In his opening narration of “The Passersby,” Serling tells viewers, “In just a moment, you will enter a strange province that knows neither North nor South, a place we call … The Twilight Zone.” When it came to the Civil War Centennial more generally, that description wasn’t too far off. Mainstream America still technically knew North and South, but wanted to collectively remember the war as equal measures Sergeant Paradine and President Lincoln. This was a reconciliatory memory narrative designed to yield American exceptionalism in the present—a narrative so powerful, its reach extended into the fifth dimension.

Matthew Christopher Hulbert is Elliott Associate Professor of History at Hampden-Sydney College. An expert on the Civil War in the West, guerrilla violence, and film history, he is the author or editor of five books. His most recent publication is a biography of Major John Newman Edwards, Oracle of Lost Causes: John Newman Edwards and his Never-Ending Civil War, released by Bison Books in Fall 2023.