Library Company of Philadelphia

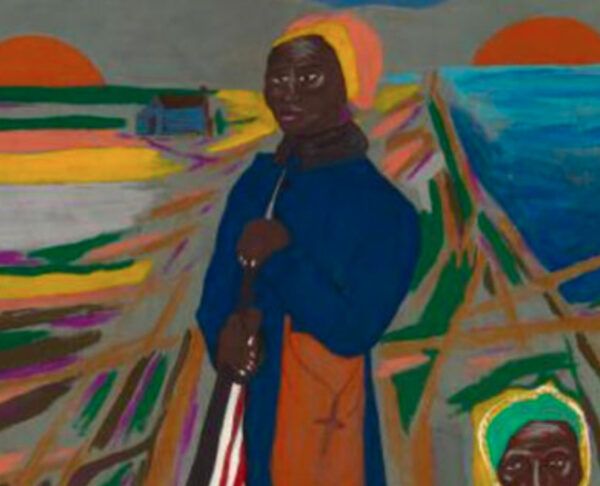

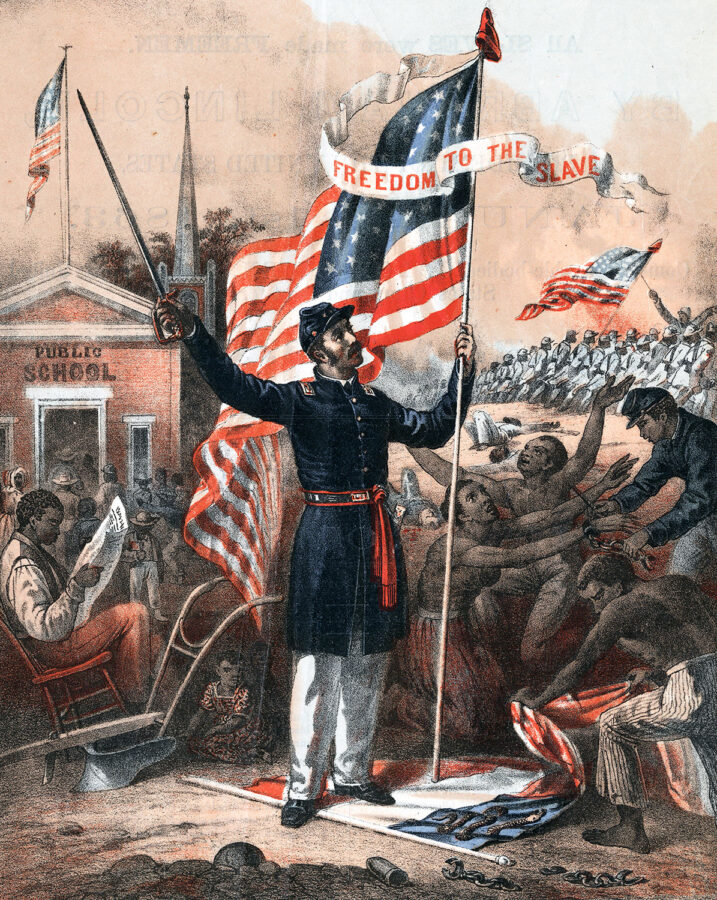

Library Company of PhiladelphiaAfter its enactment in January 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation effectively transformed the Union Army into an instrument of liberation, a change not universally embraced among its white soldiers, including officers like Colonel Joseph D. Hatfield. Shown here: a recruitment poster from 1863 evokes the freedoms granted by the proclamation in appealing to potential African-American volunteers.

In February 1863, the war between the United States and the Confederacy faced a sea change. The Emancipation Proclamation had gone into effect in January, freeing by executive order more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist states. The effectiveness of President Abraham Lincoln’s monumental proclamation still rested squarely on the success or failure of Union military enterprises and depended primarily on the army’s ability to subdue large areas of rebellious territory to a degree that made implementation of the order possible. Thus, while the Emancipation Proclamation originated as a policy measure encompassed within the executive branch of the U.S. Government, much of the burden of executing and enforcing that policy lay with the Union armies then campaigning across the vast theaters between the Atlantic and the Trans-Mississippi and beyond.

The Union army’s reception of the proclamation was not universally positive, particularly with the forces struggling to subdue Confederates in Tennessee and elsewhere. As historian Kristopher Teters found, “[e]mancipation was very controversial among western theater officers. When the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued in September 1862, a significant number of officers vehemently opposed it, and this strong opposition continued at least through the first half of 1863.” As Teters writes, “[m]any of these officers were midwesterners who reflected their region’s racial animus…. In short, the war was not a revolutionary experience for these officers when it came to race.”1 While readers might take issue with Teters’ regional characterization on matters of race, it is clear that emancipation was not a universally approved policy for some echelons of the Union army.

National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryWilliam S. Rosecrans

The Union army’s evolution into an instrument of liberation was at times bitterly divisive. That internal conflict serves as a means to understand not only the moral issues surrounding the Civil War, but also as a window into the changing role of the army in a democratic republic and into the ways in which individual decisions played out inside military leadership.

Major General William S. Rosecrans, commanding the Union Army of the Cumberland, approved of the Emancipation Proclamation. So much did Rosecrans agree with it that he wrote a letter of congratulation to the Ohio Legislature, the representative body of his home state, expressing his enthusiasm for the order. Rosecrans went further and had his letter read to his army in Tennessee on February 15. While he clearly wanted the focus of the army to expand to encompass liberation, his sentiments incensed at least one of his officers.

Colonel Joseph D. Hatfield, commanding the 89th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, was outraged at Rosecrans’ letter and its public reading to the army. His regiment, stationed at Nashville, had been organized in Cincinnati in 1862, and Hatfield became colonel after the original commander resigned.2 Rosecrans’ letter included the phrase, “This war is prosecuted to sustain law, good order, our sacred rights,” and that proved too much for Hatfield.

Hatfield’s reaction was explosive, and was said to be as follows: “I will give Rosecrans the handsomest present he ever had in his life, if he will make me believe any such stuff.” He went on in the hearing of other officers and men, fuming, “Abe Lincoln’s Nigger Proclamation will damn him to eternity; future generations will rise up and curse him; this war is carried on for the benefit of the nigger, and nothing else, and will never be stopped until that question is dropped.”3 Rosecrans’ statements had touched a nerve, and Hatfield’s anti-emancipation views (or, perhaps it was Rosecrans’ characterization of emancipation as implying “sacred rights”) were so aroused that he could not, or would not, restrain himself.

Months later, a civilian visitor to the 89th Ohio’s camp vented to the colonel about the recent arrest in Dayton of Clement Vallandigham, the notorious leader of the Democratic Party’s Copperhead anti-war faction, declaring, “Vallandigham’s arrest was a political move; he was arrested because he is a Democrat; it is not treason for a man to express his sentiments; by God, I’ll express my sentiments every and any where. The d—l nigger is at the bottom of the whole affair.” Granville Jackson, a lieutenant in the regiment, took exception and Hatfield was said to have ordered Jackson “to shut his mouth, and never open it again on such a subject,” perhaps hoping to protect his angry visitor from recrimination for “treasonable” language.4

Whatever his intentions, they were professionally calamitous. On May 10, 1863, Hatfield was formally arraigned and charged with offenses including conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline, conduct calculated to produce mutiny, speaking disrespectfully of his superior officer, protecting the utterance of treasonable sentiments, and incompetency. After a trial by court-martial, Hatfield was found guilty on all counts except protecting treasonable sentiments. His sentence was immediate dismissal from the army.5

Hatfield’s inability to restrain his criticism of national policy cost him his military career, removed an experienced leader from an important position during war, and enshrined him in the historical record in distasteful and humiliating fashion. But his example illustrates another facet of military decision-making in the Civil War context beyond the details of battles and campaigns. By regulation and tradition, army officers are required to follow orders, but also to understand their place in the republic.

Civil War officers like Hatfield demanded the citizen’s time-honored right to participate in public life and government and to voice their discontent and criticism of elected leaders. While Hatfield’s views were odious in the extreme, and his decision to voice them utterly misguided, he no doubt believed himself within his rights as a man with the dual stature of citizen and soldier. As a volunteer officer, Hatfield led and fought under the militia traditions that constituted a central part of antebellum society’s social fabric, where military service often reflected the values and political characteristics shared in the soldiers’ home communities.

There is, of course, the question of how typical an officer like Hatfield was in the Army of the Cumberland; his response seems out of proportion, and his example, particularly the court-martial that proceeded from it, was not a widespread occurrence. However, what Hatfield did not recognize was that his failure to restrain his impulses constituted a threat to the discipline and structure of the military that could not, and ultimately would not, be permitted in an army subject to civilian leadership. The consequences ruined his reputation and military career.

Andrew S. Bledsoe is associate professor of history at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. He is the author of Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2015); co-editor, with Andrew F. Lang, of Upon the Field of Battle: Essays on the Military History of America’s Civil War (LSU Press, 2019); and author of the recently released Decisions at Franklin: The Nineteen Critical Decisions That Defined the Battle (University of Tennessee Press).

Notes

1. Kristopher A. Teters, Practical Liberators: Union Officers in the Western Theater During the Civil War (Baton Rouge, 2018), 2.

2. Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (Des Moines, IA, 1908), 210.

3. Adjutant-General’s Office, General Orders from June 6-7, 1863 (United States War Department, 1863), General Order No. 134, 2.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid., 3.

Related topics: African Americans, emancipation