It’s easy to miss what remains of the Salem Church battlefield, and if not for the stone statues that stand sentinel next to the roadway, you might not know there’s a battlefield there at all. Without them, it’s easy to mistake Old Salem Church itself as nothing more than a quaint brick structure next to a graveyard on a postage stamp of green, hemmed in by parking lots, strips malls, and mutli-lane state roads packed with cars.

The statues, erected by veterans of the 15th and 23rd New Jersey Infantry, are pretty much the only reminders of the martial history of the ground. Even the ground itself is gone—graded flat and hauled away in dumptrucks in an effort to level the area for development.

But here, the Army of the Potomac’s last best hope of the Chancellorsville campaign ran into ruin. Even as the main body of the Union army reeled under woozy leadership and aggressive Confederate attacks, the Union VI Corps struggled to get into the fight. In doing so, the corps found a fight of its own—one that has largely been forgotten.

Most visitors to the Fredericksburg battlefield do not realize that Union soldiers did manage to break through the Confederate position behind the stone wall—in May of 1863.

Instead, visitors focus on the futile Union charges against the position that took place on December 13, 1862. Major General Ambrose E. Burnside sent seven waves of men against the wall in an effort to support his main attack at the south end of the field against Confederates on Prospect Hill; the latter field of attack is known today as Slaughter Pen Farm. As that attack unfolded, then sputtered out, the demonstrations against the stone wall took on a horrible life of their own, resulting in some 8,000 Union casualties on the north end of the field. (In comparison, Confederates there suffered just under 1,000 casualties, many of whom were victims of accidental friendly fire.)1

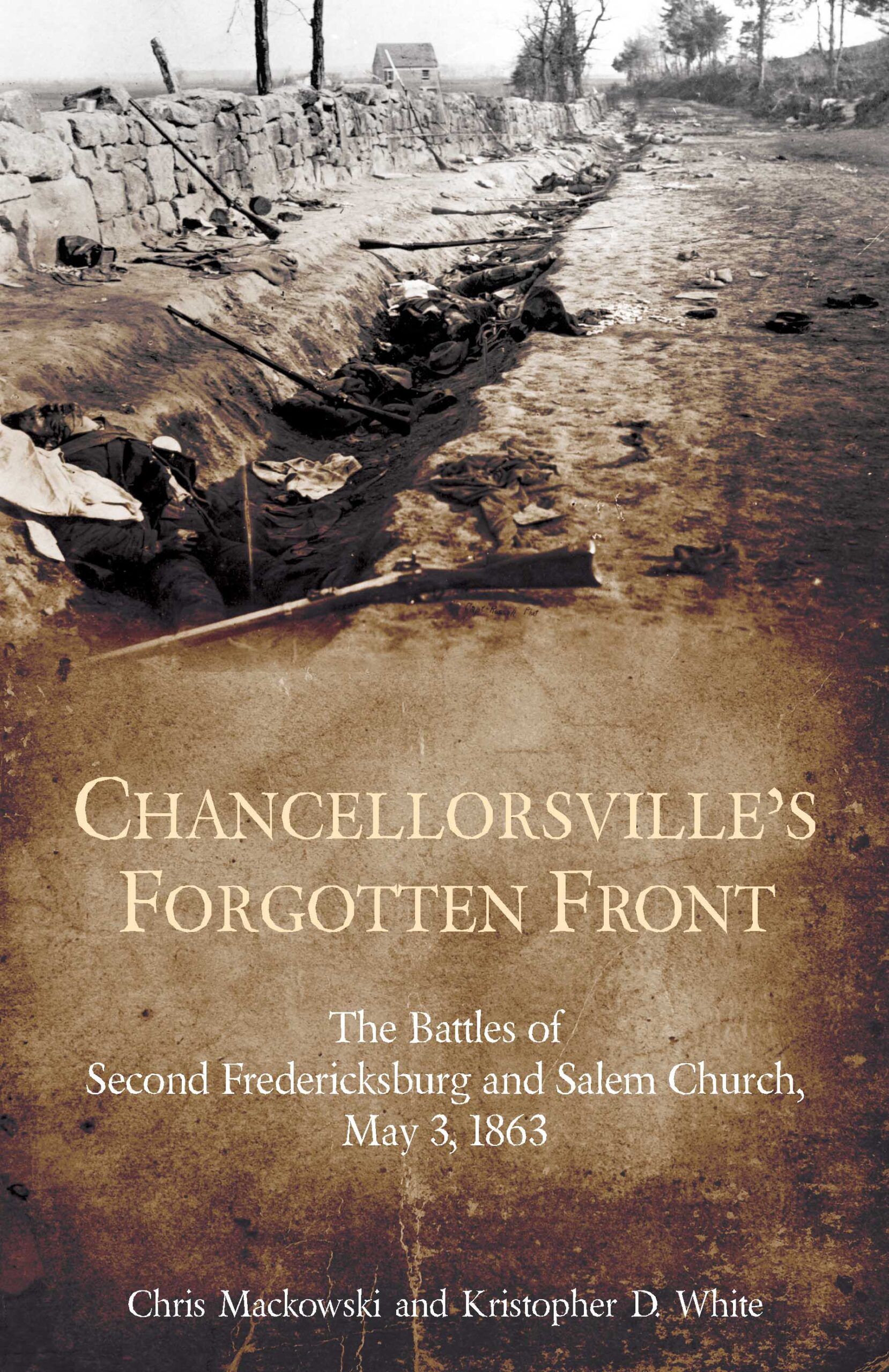

A walk along the Sunken Road and stone wall today is a little like walking back in time. In 2004, the city of Fredericksburg relinquished its right-of-way on the Sunken Road, turning over possession to the NPS, which promptly initiated efforts to restore the road to its wartime appearance. Through extensive archeology and with the help of old photos, the Park Service recreated the stone wall and the gravel road itself.

The wall, as it turned out, was far sturdier than the fieldstone wall constructed back in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps along the southernmost stretch of the road. The original wall was constructed from quarried stone. Two feet thick and four and a half feet high, it provided the Confederates with a formidable shield.

Visitors might be familiar with a post-battle photo of the stone wall and Sunken Road that shows Confederate dead lying in the road. Abandoned muskets and other detritus of battle—an overturned haversack, an unfurled bedroll, a canteen—are scattered around them. The body closest to the foreground, twisted, blackened from gunpowder, frequently gets cropped out.

The image, taken by Andrew J. Russell, came in the wake of the May battle, not the battle in December—but most visitors don’t even know the May battle took place. All eyes in May focus to the west, beyond Salem Church, to the crossroads at Chancellorsville in the heart of the Wilderness—a 70-square-mile “region of gloom” that sprawled across north Spotsylvania and Orange counties.

Yet this second battle of Fredericksburg proved the one bright spot in Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s otherwise dismal experience that May. At Second Fredericksburg, the Union VI Corps overran a Confederate position that had, until that point, grown legendary in the minds of Federal soldiers because they were defeated on that same ground, in front of that same stone wall, four and a half months earlier. By taking the position, “[t]he troops behaved most nobly, and were duly praised,” observed one newspaper correspondent.2 The Federals drove off some of the Confederacy’s scrappiest officers—Maj. Gen. Jubal Early and Brig. Gen. William Barksdale—and positioned themselves perfectly for a strike at the rear of the main Confederate army at Chancellorsville. “Ah, we anticipated a good time,” wrote a New York private.3

But as the VI Corps moved westward, things unraveled. “How different everything might, nay, would have been, if we had had the cooperation of even a small part of the immense force with Fighting Joe Hooker [at Chancellorsville]!” wrote R. F. Halsted, a member of Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s staff: “Why did he not keep Lee occupied so that he would not have dared to turn his back to Chancellorsville, to fall upon us? Or if, finding that he had so left him, why did he not know it and act accordingly; fall upon the rear of his column as it came down upon us? What was Hooker there for? To entrench himself, with six corps under his command, and expect and even order one single corps to march right through the enemy, to ‘crush and destroy,’ were the words of his order to the General, ‘any force which might oppose itself to’ our march?” 4

“Thus we find the army paralyzed at the very time when the capture of Fredericksburg Heights by Sedgwick, and his approach to the rear of Lee, should have been a signal to us for the redoubling of efforts,” wrote Col. Charles S. Wainwright in his diary. He called it “the decisive moment.” “Everything could yet have been saved,” he wrote; “yet all was lost.”5

“All was lost”—Wainwright had no idea how prophetic those words would be, considering just how much of the story has been forgotten: how Second Fredericksburg has been subsumed by First Fredericksburg; how the grisly images of the dead have been cropped from photos in an effort to sanitize them; how the battlefield at Salem Church has been bulldozed and paved and commercialized; how the very terrain itself has been hauled away in dump trucks, forever altering the topography.

The battle of Chancellorsville hinged on the VI Corps’ movement at Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church, and Hooker’s ability to take advantage of the opportunities opened by these operations. Yet in the shorthand of history, the actions at Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church get noticed only as a footnote when critics cast aspersions at Sedgwick in an attempt to scapegoat him—a tradition that dates back to Fighting Joe Hooker himself, who tried to salvage the nearly mortal blow his reputation suffered in the middle of the Wilderness.

We owe it to those New Jersey boys who still stand sentinel over the battlefield, and all their comrades who fought and fell there—to the men of the North and to the South—to look more closely at the battles of Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church, the forgotten front of Chancellorsville.

Chris Mackowski is a professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at St. Bonaventure University in Allegany, New York, and works with the National Park Service at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. Kristopher D. White is a historian for the Penn-Trafford Recreation Board, served as a staff military historian at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, and is a former Licensed Battlefield Guide at Gettysburg. Mackowski and White have co-authored several books, including Chancellorsville’s Forgotten Front: The Battles of Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church, May 3, 1863; Simply Murder: The Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862; and A Season of Slaughter: The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, May 8-21, 1864. They also co-founded the blog Emerging Civil War, which can be read at www.emergingcivilwar.com.

1 Frank O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Baton Rough, LA, 2003). O’Reilly delves into the topography of the Sunken Road sector and the effect it had on the Confederate defensive line there. Brigadier General Thomas R.R. Cobb’s Georgia brigade, specifically the 24th Georgia and Phillip’s Legion, received friendly fire from men of the 15th and 46th North Carolina of Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom’s brigade. The Georgians were forced to send two runners to the rear in an attempt to tell the Tar Heels to stop firing into their backs. The fire also left evidence in the form of battle scars that still exist on the Innis House. The friendly fire ended when the North Carolinians shifted into the Sunken Road itself to reinforce their Georgia counterparts.

2 Albany (NY) Evening Journal, May 20, 1863.

3 Jacob Bechtel to Candis Hannawalt, 59th New York, May 13, 1863, in the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park bound manuscript collection.

4 R. F. Halsted to “Miss Sedgwick,” in Carl and Ellen Battelle Stoeckel, eds., Correspondence of John Sedgwick Major-General, 2 vols. (New York, NY, 1903), vol. 2, 124-125.

5 Allan Nevins, ed., A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, 1861-1865 (New York, NY, 1998), 198.

Cover art courtesy of Savas Beatie; present day Sunken Road courtesy of the authors.

Excerpt from Chancellorsville’s Forgotten Front: The Battles of Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church, May 3, 1863, published by Savas Beatie LLC, May 2013. ISBN: 978-1-61121-136-8, Hardcover, 432 pages.