Library of Congress

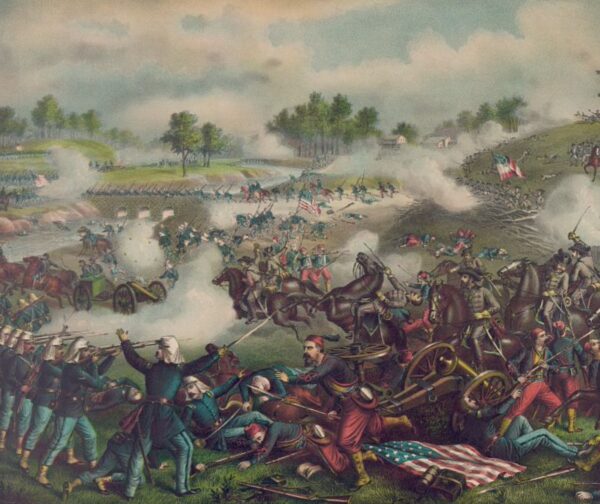

Library of CongressA portion of a Kurz & Allison lithograph of the Battle of Bull Run—or First Manassas, depending on your perspective.

It has become fashionable among some historians and public commentators to stop using many basic terms associated with the Civil War era. Examples include substituting “enslavers” for “slaveowners,” “enslaved persons” for “slaves,” and “labor camps” for “plantations.” Labeling the conflict “The War Between the States” long ago lost currency except as a clear expression of sympathy for the Confederacy. More complicated are “Manassas” versus “Bull Run” or “Sharpsburg” versus “Antietam,” with the first in each pair offending some people as too favorable to the Confederacy. I believe identifying displaced African Americans as “refugees” rather than as “contrabands” is both accurate and useful, though the latter term was widely used by both sides during the war. And I long ago stopped framing the conflict between “North” and “South,” preferring what I consider the more accurate positioning of the “United States” against the “Confederacy.” After all, four states of the South—Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware—never left the United States, and a big chunk of the most important southern state broke away to establish itself as loyal West Virginia. But even the use of “Confederacy” can provoke pushback from critics who insist it conveys an undeserved sense of legitimacy to a massive proslavery rebellion.

This last point summons to mind David M. Potter, who 60 years ago observed that historians sometimes used “the attribution of nationalism as a valuative device.” A superb scholar of mid-19th-century U.S. history, Potter believed that some scholars denied nationality to groups they considered morally off-putting—a perfect example of which would be Confederates and their slavery-based society. “To ascribe nationality to the South is to validate the right of a proslavery movement to autonomy and self-determination,” stated Potter. Many 20th-century historians proved unwilling to do this, he added, though that moral position sometimes “impelled them to shirk the consequences of their own belief that group identity is the basis for autonomy.”

The battle over terminology often stems from an effort to gain attention by focusing on language rather than on historical substance. In an intensively studied field crowded with works of excellent scholarship, resorting to arguments about language can give someone who has little new to offer the appearance of originality. Such deflections often represent an effort, and here I will echo Potter, to claim moral high ground based on 21st-century conventions and assumptions. To put it another way, these deflections make it all about us and how superior we are to past generations.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressPortion of a Civil War envelope that shows a shield and star bearing message “The Union forever.”

Calls for adopting new terminology can lead to utterly ahistorical positions that obscure, rather than illuminate, crucial aspects of the Civil War. Perhaps the most obvious example of this phenomenon lies in calls to avoid using “Union” when addressing the people, government, and armies of the United States. A pair of examples will illustrate this point. One publisher announced that “while the historiography has traditionally referred to the ‘Union’ in the American Civil War as ‘the northern states loyal to the United States government,’ the fact is that the term ‘Union’ always referred to all the states together, which clearly was not the situation at all. In light of this, the reader will discover that the word ‘Union’ will be largely replaced by the more accurate ‘Federal Government.’” Another examination of terminology suggested “that we drop the word ‘Union’ when describing the United States side of the conflagration” because the “employment of ‘Union’ instead of ‘United States,’ implicitly supports the Confederate view of secession wherein the nation of the United States collapsed…. In reality, however, the United States never ceased to exist.” “The dichotomy of ‘Union v. Confederacy’ lends credibility to the Confederate experiment,” this author concluded, “and undermines the legitimacy of the United States as a political entity.”

Such treatment of “Union” highlights the need to engage with historical characters on their own ground if the primary goal is to understand the era and its people rather than to feel good about ourselves. Whatever the publisher quoted above might think, millions of loyal citizens of the United States would have found puzzling a sterile equation of “Union” to the “Federal Government.” For them, Union represented the legacy of a founding generation that sacrificed blood and treasure to establish a form of government that gave ordinary people a political voice and the possibility of rising economically. That legacy represented a grand experiment, they believed, the best chance for small “d” democracy to thrive in a western world that seemed to be falling ever more surely into the chilling embrace of oligarchy and aristocracy.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressA crowd gathers outside the U.S. Capitol to hear Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address in March 1861.

Abraham Lincoln conveyed the profound meaning of Union for the wartime generation. His first inaugural address included a foundational history lesson. Older than the Constitution and “perpetual,” the Union stemmed from the Articles of Association in 1774, the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the Articles of Confederation in 1778, and, finally, the Constitution in 1787, whose framers during a stifling summer of debate in Philadelphia had built on the documents from 1774–1778 “to form a more perfect union.” Summoning images of a shared democratic destiny, Lincoln closed on a lyrical note that tied Americans in 1861 to all previous generations: “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

The notion that alluding to “Union” could buttress the Confederacy’s credibility would have shocked residents of the United States in 1861–1865. Indeed, it is breathtakingly ahistorical and reveals a great deal about the United States in the 21st century and very little about the nation that fought a great civil war. Proslavery forces had sundered the Union in 1860–1861 and founded a rival republic. First to last, the overriding goal of the loyal citizenry was to save the Union—in the end, an improved version of the Union without slavery—and to crush the Confederacy. As Lincoln put it in December 1864, “In a great national crisis, like ours, unanimity of action among those seeking a common end is very desirable—almost indispensable…. In this case the common end is the maintenance of the Union….” The idea that rallying a loyal citizenry in the name of Union somehow lends credibility to the Confederacy invites not just skepticism but scorn.

Gary W. Gallagher has published widely on the era of the Civil War, including several articles in The Civil War Monitor.