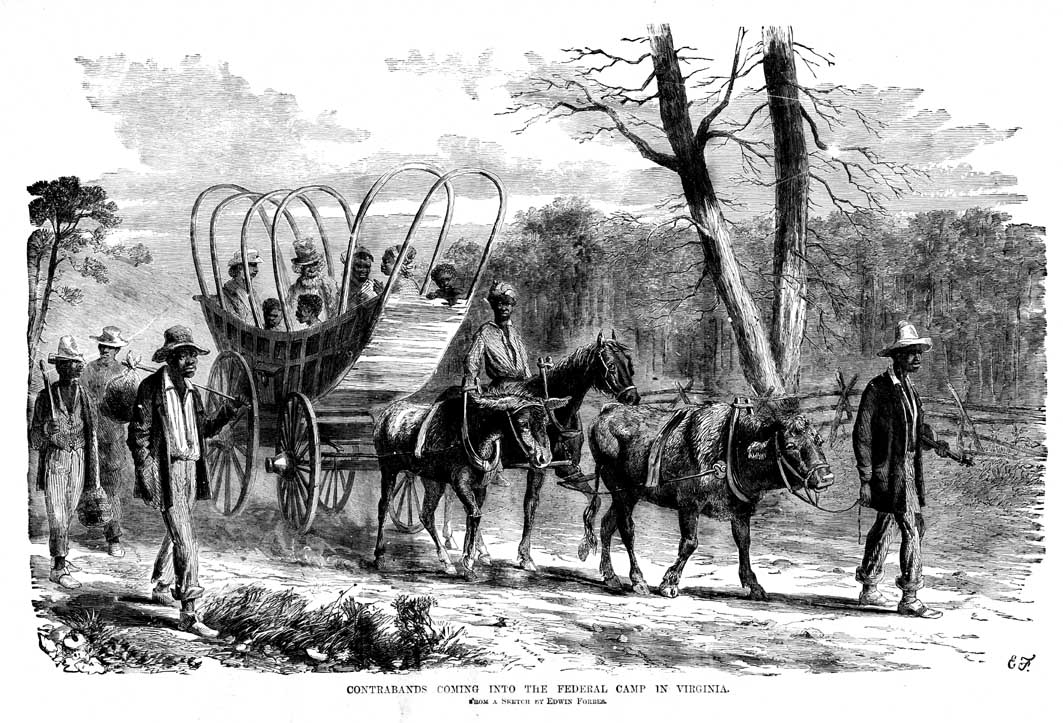

There’s a lot that remains unsettled about the Civil War: “Manassas” or “Bull Run”? “Civil War” or “War Between the States”? Forget the big questions about what the war was about: we cannot even agree on something as simple as what words to use to describe what actually happened between 1861 and 1865. It’s the sort of disagreement that isn’t going away anytime soon, because there’s another hugely momentous event of the war—one that is gaining renewed attention these days—that does not yet have an agreed-upon name: the mass flight of hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children away from slavery and into Union army camps, a migration that arguably pushed emancipation onto Lincoln’s wartime agenda.

Was it the flight of “slaves”? “Fugitives”? “Freedpeople”? “Refugees”?

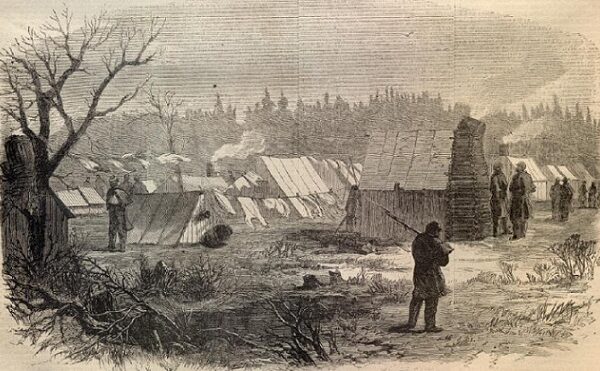

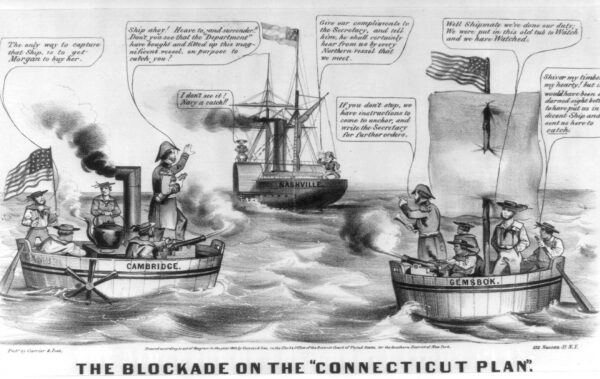

Or—and here’s the real sticking point—are they better known as “contrabands”? Back in 1861, General Benjamin Butler certainly thought so. He was the first to admit these individuals into Union lines at Fort Monroe, Virginia, that year, setting a precedent that essentially opened the floodgates for hundreds of thousands more to flee to wherever the Union army occupied the South. To Butler it was a term that made his act seem legal: to see these individuals as “contraband” was to see them as enemy property, and therefore, as something allowable to seize in a time of war. Butler’s term took off—and became the central organizing term in the Union army’s bureaucracy. In some places the man appointed to oversee this population was called a “Superintendent of Contrabands,” while new aid societies forming in the North to assist them sometimes took the word too, such as the Contraband Relief Commission of Cincinnati.

But never was there a consensus about it. General John E. Wool, Butler’s successor at Fort Monroe, preferred the word “vagrant” over “contraband,” betraying his anxiety over whether the escaped slaves would become permanent charity cases (he also used “African” too, as in a report he issued entitled “Africans in the Fort Monroe Military District”). To others, especially among the religious white northerners more sympathetic to the antislavery cause, Butler might as well have come right out and called them “property,” as the two terms were coequal in their eyes and led the American Missionary magazine to spend an entire article in February 1862 discussing its preference for “colored refugees” instead. Another missionary simply explained that “contraband” was “a term not fit for a human being.”

Most telling of all, perhaps, there is little to no evidence that the ex-slaves used the term “contraband” to describe themselves.

The term fell out of usage pretty quickly toward the end of the war, especially once the Emancipation Proclamation, and later, the 13th Amendment, guaranteed freedom. The former slaves were at that point more commonly known as “freedmen” (as in, the “Freedmen’s Bureau,” the postwar federal agency established to assist former slaves).1

But the term “contraband” is making a comeback in some of the most important recent efforts to uncover and preserve this history. In Hampton, Virginia, an organization founded in the 1990s to establish a museum and preserve nearby Fort Monroe as a site of African-American history, has taken as its name the “Contraband Historical Society.” More recently, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, turning its attention to preserving sites of slave flight in the war, entitled a conference on the subject, “Contraband Heritage.” The National Park Service has officially referred to one of its efforts to preserve this history, at Corinth, Mississippi, the “Corinth Contraband Camp.” And I’ve also found it necessary to use the word “contraband” around scholars, as it is the most familiar term to them.

Why would “contraband” be making a comeback when so many other racial terms have successfully been put to rest (at least in polite society)? Is it because “contraband” fell out of usage after the war and did not become part of the vocabulary of Jim Crow? That it did not make a resurgence, like the Confederate flag did, during the Civil Rights movement to defend the interests of white supremacy? Is it less tainted—and, therefore, more acceptable?

Certainly the term’s reemergence is not complete. Step outside the circles of those well acquainted with this history and the term means nothing. I’ve received more than a few puzzled looks from friends and family when I mention I am studying “contrabands.” And although I thought my 7-year-old daughter might know what I was talking about after reading the American Girl doll books about Addy Walker, a child who fled slavery during the Civil War with her family, she drew a blank too, as none of the volumes in this very popular series mentions the word “contraband” even once.

This may signal an opportunity to come up with another term that’s a better fit for a human being. And yet, when this precise idea was raised at a recent conference on slavery in the war, it only unleashed vigorous debate. To use another term would be impractical, some argued, as the word “contraband” is all over the Civil War records and one must confront it while researching the past. Even worse, others suggested, to deliberately avoid the term would be like sanitizing the historical record. Why deny yet another aspect of slavery’s difficult history?

These are good questions. But I think there is another reason out there for the inclination to grasp onto the term “contraband.” Those who used the term in the 1860s understood that the men and women of this era were experiencing something very distinct—a transitional period somewhere between slavery and freedom—so a distinct language was needed to describe their unusual position. To call them “freedmen” or “slaves” would have been to overlook the period of limbo during which they were not really free but not really enslaved while living near the Union army. We likewise need a term today that acknowledges and preserves this transitional status—but if it’s not “contraband,” then what should it be? As with many other semantic battles of the Civil War, this one could take some time to answer.

Amy Murrell Taylor is associate professor of history at the State University of New York at Albany and the author of The Divided Family in Civil War America (University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

Photo Credit: Frank Leslie’s The Soldier in Our Civil War.

Notes:

1. See Kate Masur’s in-depth study of the transition from one term to the other, “‘A Rare Phenomenon of Philological Vegetation’: The Word ‘Contraband’ and the Meanings of Emancipation in the United States,” Journal of American History 93, no. 4 (March 2007): 1050- 1084