Harper's Weekly

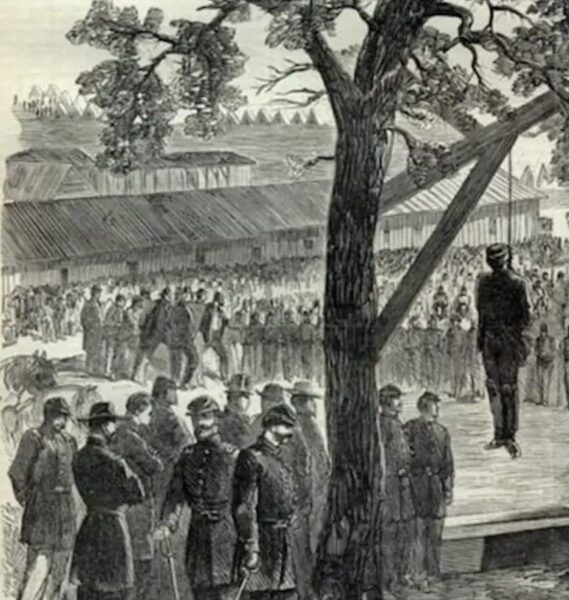

Harper's WeeklyA Civil War execution

In 1865, the United States Sanitary Commission, a private relief agency that supported sick and wounded soldiers during the Civil War, published a volume of Union soldiers’ writings titled Soldiers’ Letters, from Camp, Battlefield and Prison. Among them was the following letter written by a Pennsylvania lieutenant to his cousins, in which he related the tale of the arrest and execution of an accused spy who had been serving as a camp sutler. It follows in full:

Brandy Station, Dec. 13th, 1863.

My dear Little Cousins

Each a note in your own handwriting! What could I prize more highly than those two original mementoes of friendship? In them was contained much in little. Did you know that there are few persons in this beautiful world of ours who can speak volumes in a very few words. You have really done it. These missives of love shall ever be kept by me, for the purpose of remembering those “little people,” who thought of a certain one; a soldier in a far distant country, who is struggling for his and their country’s existence. Now, some “folks” are ignorant and simple enough to think and say that children are of no consequence; but what would society or the community at large be without them? Worse than a desert drear. Why, to have those little innocent, cheerful, and always playful people excluded, would be worse than death! We would all plead that time should end with the setting sun; for they, and they only, make the world what it is—happy or unhappy. So, my dear little cousins, bear in mind that your two little missives will be always carried next the spot that clarifies my blood,

“When the smoke of the roaring cannon surrounds me, And the lightning of battle gleams brightly about me!”

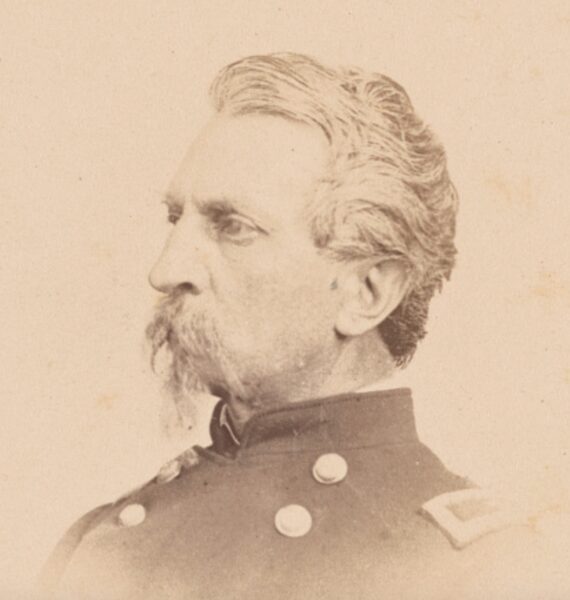

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUnion general Philip Kearny

What have I in my possession to send you, to show that I am of that class that can appreciate favors? A medal? Yes—a medal; and one which I purchased for the express purpose of wearing into battle, so that, providing I had been unfortunate and met the fate of many of my comrades, I could easily have been recognized by it. But, thanks to One, who is Ruler over all, it never had the opportunity of proving its usefulness. My name, place of residence, regiment and company, all the battles I was ever engaged in, up to Chancellorsville, is inscribed upon it; besides, there is attached to it the photograph of our old division commander, General Kearney, who had the misfortune to run against an obstacle in the dark, in the shape of a rebel minie ball, which caused instant death. Above the photograph is a red square badge, representing the 1st division, 3d corps, Army of the Potomac.

There is a story connected with the medal, which is very interesting. Please listen a little while longer, and you shall hear it. The man of whom I purchased it had a roving commission as sutler, in the Army of the Potomac. He was known by every officer and soldier as a sutler, poet, musician, singer, ventriloquist, magician! He was also known as a professed Christian, a chaplain, an agent for the American Tract Society, and soldier’s friend! He was a smart, shrewd hypocritical character—one that would take the advantage of a person the first opportunity. It appeared to me that money was all he cared about while he lived. Money, money, money; he would do any thing for money.

The last time I saw him was on our way back from the Pennsylvania campaign. He had been caught, tried, condemned as a spy, and sentenced to be hung on an apple-tree, southeast of Frederic City, Md. I saw him three days after, or rather his body, still hanging from the tree! He was to hang there five days and five nights. He made a full confession of his guilt after the rope had been placed about his neck! He confessed that he had been a rebel spy ever since the war broke out, and had been the cause of thousands of our troops being killed, wounded, and captured. The soles of his boots were one and a half inch thick! [I]t was the place where he deposited all of his important documents. I could tell you much more about his life since I became acquainted with him. In truth, the history of his career in the army would be worth reading. Twenty sheets of foolscap paper closely written over would not contain it! Suffice it to say, that it took him forty-seven long years to find out that the penalty of sin is death.

Now, little cousins, please accept this medal as a sort of romantic present from me. Now please don’t stop writing, for your letters are better than the best.

Lieut. Harvey M. Munsell

Penn. Vet. Vols.