Library of Congress

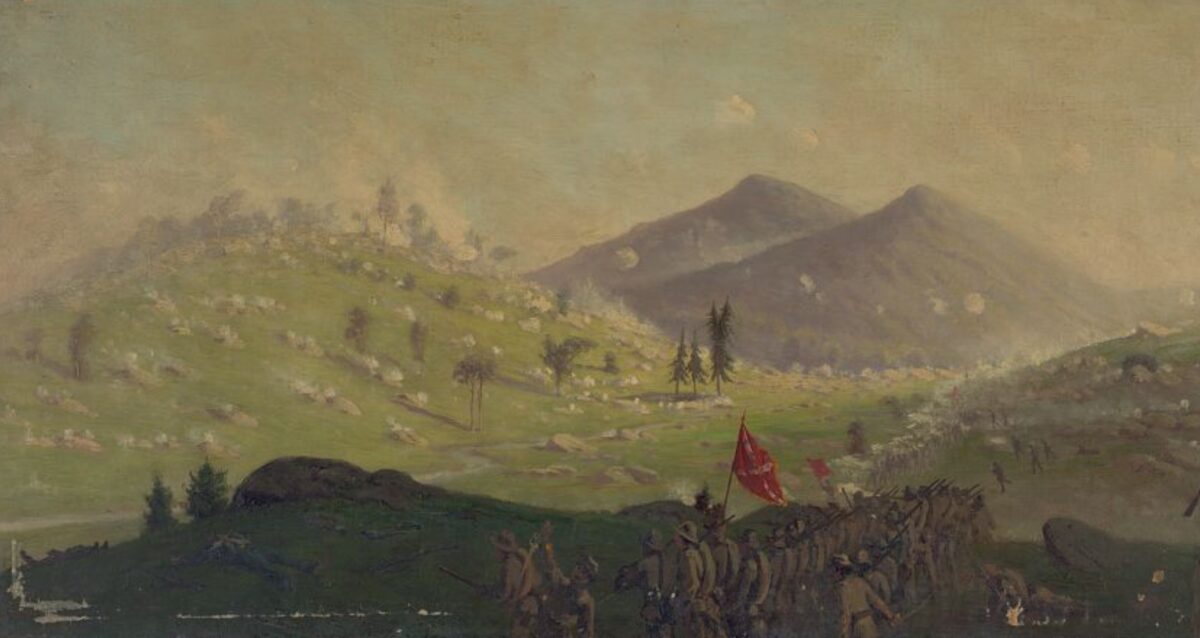

Library of CongressThis Edwin Forbes’ painting of the Battle of Gettysburg depicts Confederate troops advancing on Little Round Top, where Color Sergeant Andrew Jackson Tozier’s actions would later earn him the Medal of Honor.

Did you know there were two officers of the 20th Maine Infantry who received the Medal of Honor for their actions during the fight for Little Round Top on July 2, 1863? Most Gettysburg enthusiasts know the regiment’s colonel, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, was one. The other was Color Sergeant Andrew Jackson Tozier, who had taken a crooked path to his date with destiny.

Tozier was born on February 11, 1838, in Purgatory, Maine, the fifth of seven children. When he was 10, the family moved to Plymouth to be near relatives. In his teens, Andrew fled his abusive alcoholic father and went to sea. In July 1861, he returned to Plymouth and enlisted in the 2nd Maine Infantry. By the next year he had been promoted to corporal and in June 1862 was wounded in the finger and ankle at the Battle of Gaines Mill, where he was captured and sent to Belle Isle prison in Richmond. He was paroled in time to rejoin his regiment in May 1863.

Soon after his return, the regiment’s two-year term of enlistment expired and it was disbanded. However, about 120 men in the 2d Maine unknowingly had signed three-year enlistment papers. Despite their objections—of course, they thought they were entitled to go home—they were held to three-year terms and transferred to the 20th Maine Infantry. Among them was First Sergeant Andrew Tozier. Considered mutineers after they refused to take up arms and continue their service, they arrived at the camp of the 20th Maine under guard. They were accompanied by orders from Major General George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac’s V Corps, to “make them due duty or shoot them down the moment they refused.”

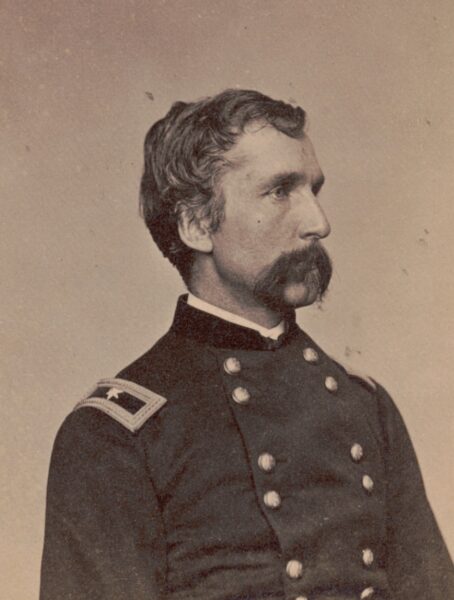

Library of Congress

Library of CongressJoshua Lawrence Chamberlain, colonel of the 20th Maine Infantry at the Battle of Gettysburg

Chamberlain, newly minted as commander of the 20th Maine, was not about to shoot fellow Maine boys. He recognized that the men may have been deceived by zealous recruiters, and knew they had demonstrated their willingness to fight over the past two years. These were battle-hardened veterans and Chamberlain immediately provided them with rations and fresh clothing. He promised he would examine their cases, deal with them “as soldiers should be treated,” and that “they would lose no rights by obeying orders.” They were assigned to different companies of the regiment and Tozier went to Company I.

With the launch of the Gettysburg Campaign in mid-June, the 20th Maine marched north with the Army of the Potomac in pursuit of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. During the march, the regiment’s color sergeant, Charles Proctor, got drunk and abusive toward officers. He was relieved and replaced by Tozier.

Tozier carried the flag in the rain and heat of that Maryland summer. When the regiment reached the Mason-Dixon Line and northern soil, the color guard unfurled its flags and the soldiers gave hearty cheers. With a great battle looming, Meade, now commander of the Army of the Potomac, issued a circular to be read to all that promised “instant death of any soldier who fails in his duty at this hour.” Gettysburg would be the first battle in which Tozier carried the national colors.

The 20th Maine and the rest of the V Corps reached Hanover, Pennsylvania, by 4 p.m. on July 1. Soon the corps was ordered—by Major General George Sykes, who had succeeded Meade—to Gettysburg, where part of the army was engaged with Lee’s advancing force. When the 20th Maine arrived early the next morning, they were held in reserve. But in the afternoon a crisis arose as Major General Daniel Sickles moved his III Corps forward from its assigned position on Cemetery Ridge, endangering the integrity of the entire Union defensive line. Meade acted swiftly, ordering Sykes to throw his whole corps in on the Union left and hold the position “at all hazards.”

The V Corps marched to the left with Brigadier General James Barnes’ division leading the way and Colonel Strong Vincent’s brigade (including the 20th Maine) at its head. A Sykes staff officer would intercept the division with an order for Barnes to dispatch a brigade to a nearby hill known as Little Round Top. Vincent, in the absence of Barnes, recognized the developing crisis—the hill, command of which would dominate the sector of the field, was then unoccupied with Confederates advancing toward it—and took it upon himself to move his men. The 20th and other regiments of the brigade took positions on the rocky hill just 10 minutes before Confederate forces attacked. The 20th Maine was placed on the left flank of the brigade and told to “hold that ground at all hazards.” Tozier took his position with the color company in the center of the regimental line. Soon Chamberlain had to realign his position to counter Alabamians attempting to outflank him on the left. He refused his line of Maine men so that it took on the shape of an inverted V, with the color company now at the point, roughly where today’s 20th Maine monument rests. Here stood Tozier and his colors.

At the center of the Maine line, the situation for the color company became dire. The companies on either side were being cut to pieces. The color company was down to just three men: Elisha Croan, William Livermore, and Tozier. Corporal Charles Reed took a bullet to the wrist and was unable to use his weapon, so Tozier traded the flag for Reed’s rifle. Tozier loaded and fired until Reed was no longer able to continue and then he retrieved the flag. At one point, Chamberlain peered through the smoke and saw Tozier standing alone where he had planted the colors. He had them resting inside the curve of his left arm as he rammed a cartridge into his musket with his right hand and discharged the weapon. Chamberlain recalled, “I first thought some optical illusion imposed upon me but as forms emerged through the drifting smoke … there stood Color Sgt. Tozier. His color staff planted in his elbow, so holding the flag upright, with musket and cartridges seized from the fallen comrade at his side, he was defending his sacred trust in the manner of the songs of chivalry.” Major Ellis Spear recalled how Tozier cooly chewed a piece of cartridge paper as he fired. He did not budge despite the storm around him. Before long, with the 20th’s ammunition nearly exhausted, Chamberlain ordered the now famous bayonet charge that drove the Alabamians from the hillside and secured Little Round Top.

Tozier continued as a member of the 20th Maine and 10 months later, at the Battle of North Anna in May 1864, he was wounded just behind his eye. A fragment of the bullet would remain lodged in his skull, but he served out his enlistment until July. Thirty-four years later, Tozier would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions on Little Round Top. The citation read: “At the crisis of the engagement this soldier, a color-bearer, stood alone in an advanced position, the regiment having been borne back, and defended his colors with musket and ammunition picked up at his feet.”

Andrew J. Tozier died at 72 on March 28, 1910, in Litchfield, Maine.

Larry Korczyk has been a licensed battlefield guide at Gettysburg National Military Park for 13 years. He has conducted hundreds of tours on the battlefield (with a specific focus on the leadership of army commanders George Meade and Robert E. Lee), is a regular speaker at Civil War round tables, and is co-author of the book Top Ten at Gettysburg (2017).

Thank you for the free article. I had never heard of Medal of Honor winner Tozier. Inspiring history!

Another overlooked hero finally getting some due respect.