Harper's Weekly

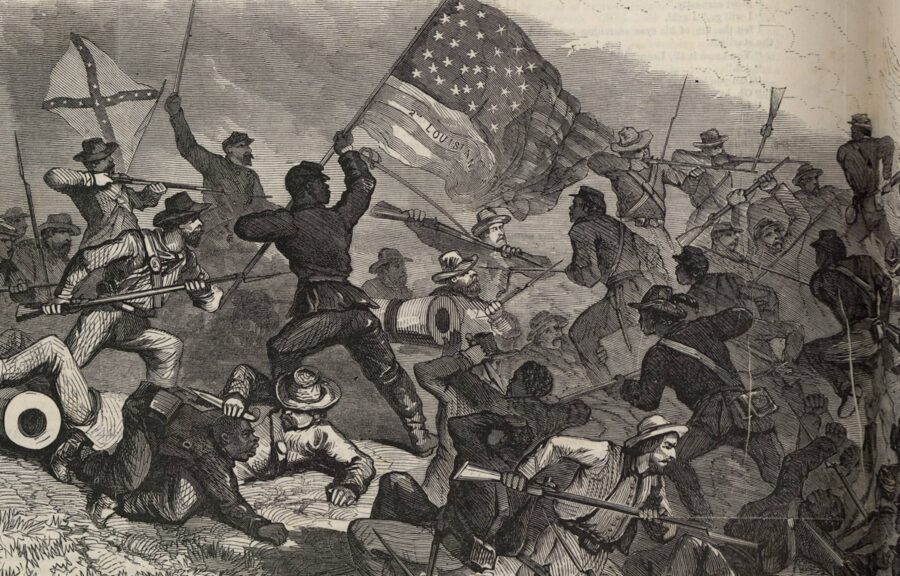

Harper's WeeklyA depiction of fighting during the Siege of Port Hudson in 1863

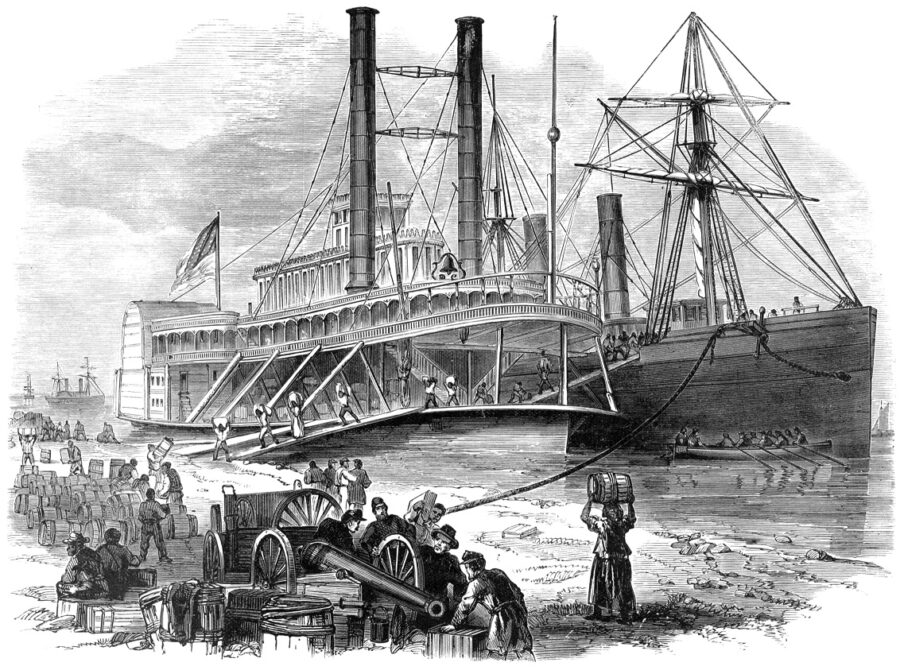

During the Siege of Port Hudson in 1863—part of the Union military’s attempt to seize control of the Mississippi River—James Kendall Hosmer, a soldier in the 52nd Massachusetts Infantry, was dispatched on temporary detached duty. He soon found himself on a steamship called Iberville headed toward Baton Rouge. While on the journey, Hosmer began, as he would later put it, “a week of hospital work—a week of most profound and soul-touching experiences—a week when work went on from day-dawn to day-dawn almost without intermission; when new resources and new strength were developed in all who were there.” Below is an excerpt of his experiences during his busy time as a hospital steward aboard the Iberville:

The attempt to storm Port Hudson was unsuccessful; but something was done then to forward our cause, because it was on this day that black soldiers underwent their ordeal. Side by side with white troops, they were exposed to a hot fire, and bore themselves well. Col. Higginson, in South Carolina, has had his men under fire, to be sure; but his fighting has been of an irregular sort. Here, for the first time, they were exposed in a pitched battle; and their praise is in every mouth. I am glad I can write that the wounded blacks received all possible attention. They lay about the steamer wherever it was airy and pleasant. The surgeons were attentive. Barclay poured out the stores of the Sanitary and Christian Commissions without stint, and we nurses did all we could. I moistened many a black fellow’s wound; and where, as sometimes happened, they were stripped, that the surgeons might more readily reach their injuries, I adjusted the screens that kept off insects and the sun. They were never otherwise than full of patience and gratitude.

I also washed the wounds and the faces of the officers at the end of the cabin, and happened to be on hand to help in a very trying surgical operation. I held the leg of the young adjutant while Dr. L cut a bullet out of the bones of the knee, in which it had become deeply embedded. It was a painful and critical operation. A few days before, I should have fainted at the sight; but, in such scenes, the sensibilities become blunted.

Every available foot of space now aboard the “Iberville,” above and below, was filled with wounded men; and four nurses, I for one, were detailed to go with the boat to Baton Rouge. All were fed, above and below. We stood at hand with wet sponges and cooling drinks; and, meantime, the steamer with her sad freight slipped rapidly down the fifteen miles to Baton Rouge. Hospitals were prepared at the old Arsenal Buildings; and, as the boat rounded to, the intrenchments and banks everywhere were crowded with people.

The boat was soon emptied of its freight. I piled up the beds, as they were vacated, on one side of the cabin; and then had a little leisure to go ashore, and see a room or two of the permanent hospital. They looked neat and comfortable. The rooms were airy; the beds clean, and protected by mosquito-bars ; the patients soon washed, and provided with food and fresh clothing. The steamer was presently on her way back. I managed to get a good dinner aboard; then spread a bed on the cabin-floor, and got an hour or two of welcome and needed sleep. I had worked very hard, and, I believe, gained the good-will of the surgeons. Besides, one or two old patients of mine, whom I had nursed in typhoid fever, had been at the landing, and, I believe, had spoken a good word for me. More and more responsibility was put upon me.

As soon as I had returned, the hospital-steward told me I was to take charge of removing a large number of wounded to the boat from the tents, who had been brought down from the field during our trip. Here were my negroes, here the nurses I could have, and here the stretchers. I went right to work. I had gained confidence, found my strength was good, and therefore was not afraid to handle even the worst cases. I dared to take hold of the stumps when it was necessary, the pierced hips, and lacerated shoulders. I had found that a quick, steady movement caused the least pain.

The Soldier in Our Civil War (1893)

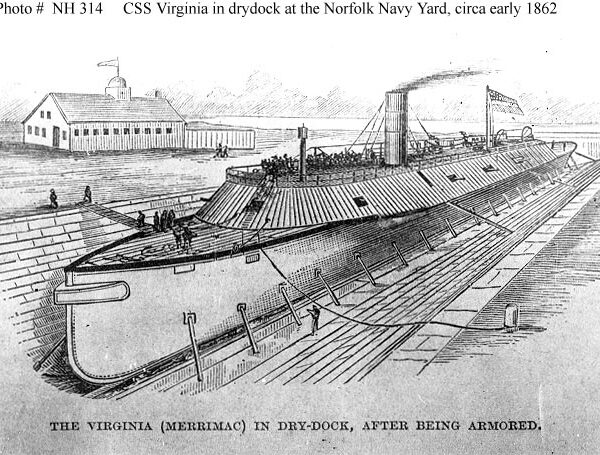

The Soldier in Our Civil War (1893)The steamer Iberville, depicted in the foreground, was the vessel on which Hosmer helped treat wounded Union soldiers.

About dark, —this was Thursday, —the task was accomplished, but only to make room for another; for now a longer string of ambulances than ever had come. The surgeons had gone to bed exhausted, and could not be disturbed. The hospital-steward was not to be found; and upon me came the responsibility of getting them all housed, fed, and cared for during the night. I had the beds laid in as good order as possible, working as I never worked before; then superintended, as well as I could, the removal of the men from the ambulances to the pallets upon the ground. It seemed as if we never had received a lot so dreadfully mangled: we certainly never received so many. With as much despatch as possible, I assigned to each his place. Commissary-teams were waiting for the ambulances to get out of the way; and we had almost to jump and run among the closely packed crowd on the floor, in the dim candle light. Outsiders, some of them officers, came in, but often hindered more than they helped, by misplaced sensibility, or unreasonable assumption of authority. The lightly wounded were to be put in the less accessible places under the eaves, as requiring least attention; the graver cases were to have the airiest beds; and the bodies of those who had bled to death in the ambulances had a place assigned to them in a tent out side. Barclay was at my right hand; a good man indeed.

Together we took hasty counsel as to moving and making comfortable the more desperately injured. How could we take hold here so as not to jar the shattered lungs? And how, with this heavy, tall fellow, terribly hurt in the groin, —how could I get my hands under the hips, so as to lift him most easily? We worked hour after hour, the sweat starting from every pore, that hot, moon-lit night, until every inch of available space was packed, and all were fed.

I do not know how many regiments were represented. There were officers of all grades. A colonel shot through the hand; a captain shot in the neck; and another, a gentleman, in the midst of his suffering, his elegant dress dusty and gory. I was hoarse with giving directions in the hubbub, and worn out with want of sleep. Toward daylight again, I found a place to lie down.

I happened to lie down in the tent where Barclay kept his stores; and, when I awoke in the morning, he was there. He never appeared to need sleep. We had an interesting half-hour’s talk. I told him about watching with the cannoneer, whose whole body was far gone with decay, and full of worms, although life yet lingered. Was it not almost a barbarity not to put him into the final sleep? Then came up the case of Napoleon, and the fever patients of his army in Syria. They, too, were sick to death; sure to become a prey to the Turk: was it so monstrous for him to propose to put them quickly and smoothly out of life? From that we got on to the question of suicide, and spoke of Godwin and French thinkers, and of Epictetus, and sages of old, who permitted such flight from life. “If the house smokes, leave it.” We thought life was too sacred a thing for man to touch. God gave it: let him take it away, when it is time.

I got up from the ground before Barclay, soaked with sweat, and with dust and blood adhering every where. I apologized for my appearance; for it was my only shirt. He gave me another out of the Sanitary-Commission stores, in which I once more felt decent.

This was Friday, —a day much like the previous ones. Besides the “Iberville,” there were two or three other steamers to take the wounded; and, one after another, they went down stream freighted. During the day, we had a fine shower, which cooled the air. To dress a wound is no slight operation. To undo gaping injuries, wash them, stanch the blood; then do them up neatly, and feel they are safe, —all this, one does not reach at once.

My hospital-service, however, was coming to a close. Saturday morning, began to arrive the Fifty-second Regiment. During the fortnight I had spent on my journey, and at Springfield Landing, they had per formed a march of one hundred and thirty miles; being part of the guard of the immense train in which the negroes and a vast portion of the wealth of the Teche and Opelousas neighborhoods were brought to the sea board. That work had been accomplished; and now, at the end of May, they had been hurried up the river to re-enforce the besieging army. Saturday afternoon, when the regiment passed the hospital on its way to the front, I bade Barclay and my old mates good-by, and fell in with the colors in my old place.

Source

The Color-Guard: Being a Corporal’s Notes of Military Service in the Nineteenth Army Corps

Related topics: medical care