West Point Museum

West Point MuseumA Civil War slouch hat with a bullet hole

In the Voices section of our Winter 2024 issue we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about the close calls they or their comrades had experienced during the Civil War. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“I was in the line of file closers hardly two paces away and just behind the man killed. We were covered with blood, fine pieces of flesh, entrails, etc., which makes me cringe and shudder whenever I think of it. The concussion badly stunned me. I was whirled about in the air like a feather, thrown to the ground on my hands and knees—or at least was in that position with my head from the enemy when I became fully conscious—face cut with flying gravel or something else, eyes, mouth and ears filled with dirt, and was feeling nauseated from the shakeup. Most of the others affected went to the hospital, and I wanted to but didn’t give up. I feared being accused of trying to get out of a fight.”

—Lemuel A. Abbott, 10th Vermont Infantry, on the effects of an artillery shell exploding nearby during the Battle of the Wilderness, in his diary, May 5, 1864

“I was sewing, one day, near one side of the cave, where the bank slopes and lights up the room like a window. Near this opening I was sitting, when I suddenly remembered some little article I wished in another part of the room. Crossing to procure it, I was returning, when a Minie ball came whizzing through the opening, passed my chair, and fell beyond it. Had I been still sitting, I should have stopped it. Conceive how speedily I took the chair into another part of the room, and sat in it!”

—Mary Ann Loughborough, on an incident that occurred during the 47-day Siege of Vicksburg, in 1863. She was among the city’s residents who took up full- or part-time residency in “caves” dug into the earthen hillsides for protection from Union artillery.

“I went up and skirmished a[nd] word was brought me that Frank was slightly wounded. The ball hit a pocket, which was full of things, broke a looking glass, the handle of a toothbrush, and a thick letter from Cousin Sarah. It merely broke the skin, making a bruise. He had not fired a single shot.”

—Seth J. Wells, 8th Illinois Infantry, on the close call his brother Frank, a fellow soldier, experienced during the Siege of Vicksburg, in his diary, May 20, 1863

State Historical Society of Iowa

State Historical Society of IowaCivil War nurse Annie Wittenmyer

“I sat down in one of the [medical] tents for a while; there was a patch of weeds growing near the tent-door. I noticed the weeds shaking as though partridges were running through them…. [T]he surgeon explained, ‘Why, those are bullets!’… Three days from that time an officer was killed while sitting in the same chair on the same spot where I had sat and watched the bullets shaking the weeds.”

—Nurse Annie Wittenmyer, on an incident that occurred during the Siege of Vicksburg, in her memoir of her wartime service. Assured by the surgeon that she was safe, Wittenmyer had remained in her chair, “watch[ing] the bullets coming over and clipping through the weeds.”

“I was blazing away at the rascals not ten rods off when a ball struck my gun just above the lower band as I was capping it, and cut it in two. The ball flew in pieces and part went by my head to the right and three pieces struck just below my left collar bone. The deepest one was not over half an inch, and stopping to open my coat I pulled them out and snatched a gun from Ames in Company H as he fell dead. Before I had fired this at all a ball clipped off a piece of the stock, and an instant after, another struck the seam of my canteen and entered my left groin. I pulled it out, and, more maddened than ever, I rushed in again. A few minutes after, another ball took six inches off the muzzle of this gun. I snatched another from a wounded man under a tree, and, as I was loading kneeling by the side of the road, a ball cut my rammer in two as I was turning it over my head. Another gun was easier got than a rammer so I threw that away and picked up a fourth one. Here in the road a buckshot struck me in the left eyebrow, making the third slight scratch I received in the action. It exceeded all I ever dreamed of, it was almost a miracle.”

—Oliver Wilcox Norton, 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry, in a letter home about the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, July 4, 1862

“We were in action about three and a half hours…. Got a bullet through my boot-leg, while we were retreating. The fire was the heaviest I have ever been under. Several of my men, that I drove out from behind trees, were killed by my side. Trees were cut down by the bullets, and bark was knocked into my face time and again by the bullets.”

—Lieutenant Colonel Stephen M. Weld, 56th Massachusetts Infantry, on the Battle of the Wilderness, in his diary, May 6, 1864

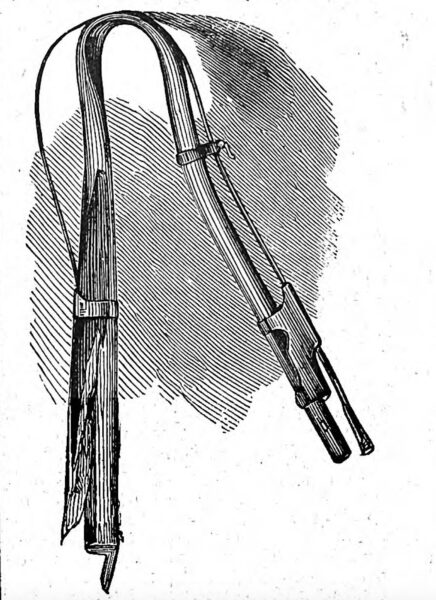

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyA wartime illustration of a rifle bent double by a cannon ball.

“One of my men … had his musket struck by a ball and bent double like a hairpin, but straightening out his arm, which was nearly paralyzed for an instant, he picked up another musket and went on, keeping his place in the line.”

—Captain Augustus C. Brown, 4th New York Artillery, on the Second Battle of Petersburg, in his diary June 18, 1864

“When their line was broken, I took my bayonet off my musket because it hurt my hand in loading rapidly, and just as I put it in the scabbard one fellow took a fair shot at me in an open place about thirty steps off. The bullet hit the handle of my bayonet, which had not been in my belt two seconds, and knocked the handle entirely off. It was driven against me with great force, blinding and sickening me so that I felt and was supposed to be fatally wounded. It seems to me that a thousand bullets and grapeshot tore up the ground around me.”

—John C. West, 4th Texas Infantry, on an incident that occurred during the Battle of Chickamauga, in a letter to his wife, September 24, 1863

“He stopped a moment, examined the wounds, picked out some of the balls that were buried in his flesh, and said: ‘This does not amount to much,’ and paid no further attention to his wounds until the fight was over.”

—Albert O. Marshall, 33rd Illinois Infantry, on Colonel Charles Edward Hovey’s reaction to being hit in the chest by “nearly spent small balls from a shotgun or musket” at the Battle of Hill’s Plantation, Arkansas, July 7, 1862, in his journal

“We were stationed on the extreme left of the line, and the rebels had a flanking fire on us, killing and wounding our men at their leisure, until we dug a flanking pit…. While I was digging, two balls hit me, one went through my knapsack, and the other hit the strap across my shoulder, but neither hurt me or scared me, for my trust is in God….”

—John R. Pillings, 86th New York Infantry, in a letter to a friend about the Battle of Cold Harbor, June 1, 1864

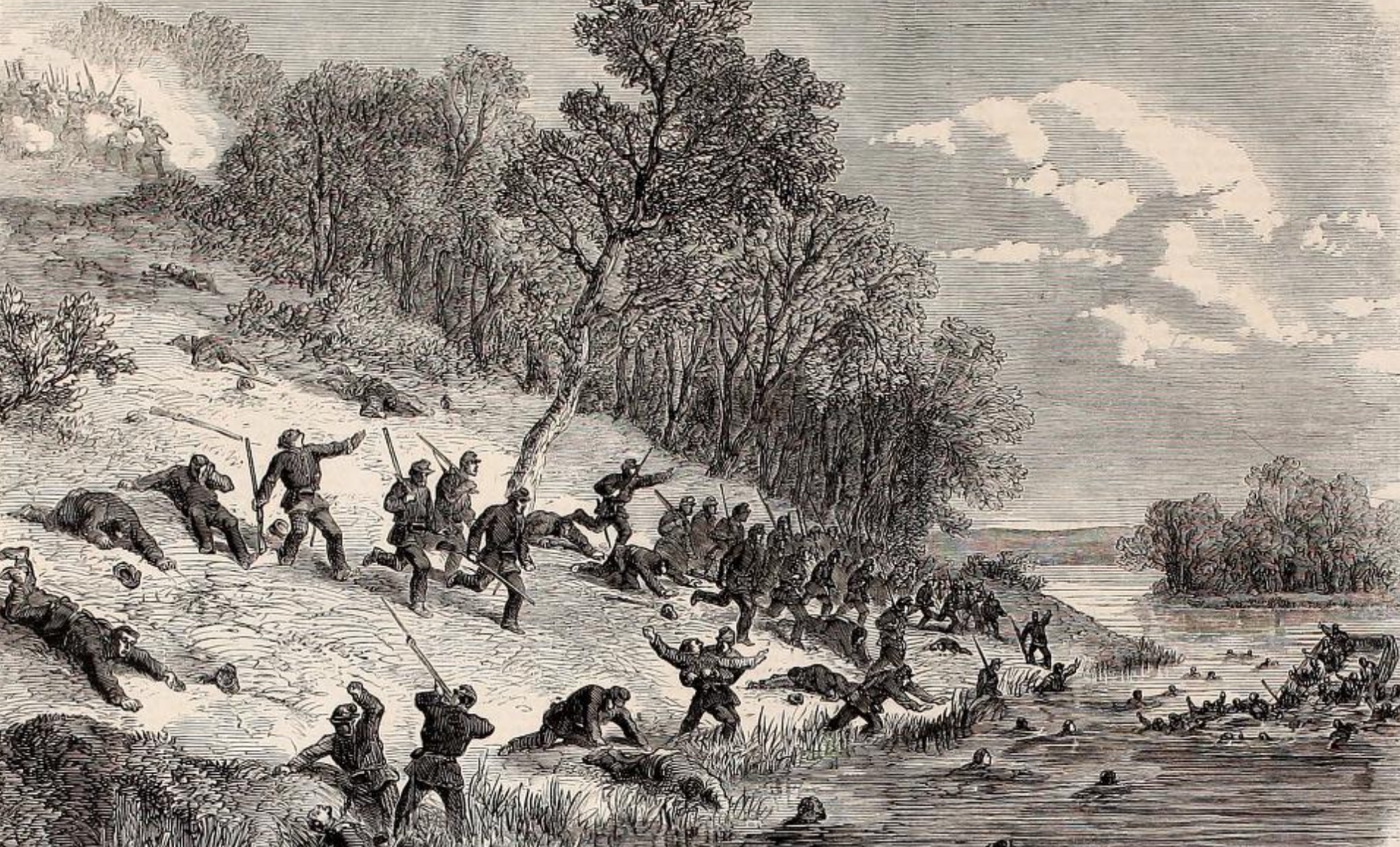

“I went through the whole of it without a scratch, not even a hole in my clothes. I was very much disappointed, as some officers had three or four bullets through their coats and caps; so I made up for it by nearly drowning myself in the Potomac.”

—Union officer Richard Derby, in an undated letter about the October 1861 Battle of Ball’s Bluff to Rev. James Means. Derby and others had had to beat a hazardous retreat, under fire, across the Potomac at battle’s end.

The Illustrated London News

The Illustrated London NewsUnion soldiers retreat in haste during the Battle of Ball’s Bluff.

“We were all standing out on the hill, when some enterprising rebel sharp-shooters opened on us, and the first thing we knew, bullets were whistling around rather lively…. Colonel Sanders and myself stayed to finish some observations we were making. We were standing close together talking when a bullet passed between us and struck a gun-carriage behind us. We concluded to take the hint and retire to cover.”

—An unidentified Union staff officer, in a letter written about the Siege of Knoxville in 1863. Within days, Colonel William Price Sanders was shot and killed by a Confederate sharpshooter.

“[T]he shell and bullets of the enemy were flying like a storm over us…. A ball came along and took about two inches of my coat away on the shoulder.”

—Alfred Davenport, 5th New York Infantry, on the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, in a letter home, July 8, 1862

“[O]nly about forty of our regiment … got off, and in my company…, only the captain, one sergeant, and myself got off! And we got bullet-holes through our clothes. I got two. Many of the boys, who had been in all the battles, and never got hit, there fell.”

—Charles N. Maxwell, 3rd Maine Infantry, on the Battle of Gettysburg, in a letter home, July 25, 1863

“When we were about halfway through the town, four rebel soldiers placed themselves across the street, at about one hundred yards distance, and coolly drew up their pieces, and fired at us as though they were firing at a target. The first one fired point blank at me, and came very near knocking me from my horse.”

—C.F. Wakeman, 3rd New York Cavalry, on an incident that occurred while he was on picket near Rocky Mount, North Carolina, in a letter home, July 25, 1863. “I should have killed the one that had fired at me had they not surrendered,” he added.

“One rebel dropped his musket, begged and received quarter, and when his pursuer had passed by, raised his piece and fired, missing his man. The cavalry-man turned his horse, deliberately rode up to him, and shot him through the head.”

—Rowland M. Hall, 3rd New York Cavalry, on an incident that occurred as he and his comrades forced the surrender of a group of Confederates during the Union advance toward Goldsboro, North Carolina, in an undated letter

“I climbed over our works, and ran like a trooper to the other line, some one hundred and fifty yards, and stopped behind a large chunk of earth on the outer slope of the crater to rest, surrounded by a mass of dead rebels, and some of our own wounded, one of whom kindly suggested to me that I was on the wrong side of the chunk; and a bullet nearly taking the top of my head off, proved he was right.”

—An unidentified Union staff officer, in an account of the Battle of the Crater written shortly afterward

“Heavy fighting. We had to fall back…. Another close shave. Just handed Corporal Flanigan, next to me, my canteen, when he dropped, shot through the head. In falling he nearly threw me from my horse.”

—Phil Koempel, 1st Connecticut Cavalry, in his diary, June 1, 1864

Letters Written During the Civil War, 1861-1865 (1898)

Letters Written During the Civil War, 1861-1865 (1898)Charles Fessenden Morse

“I had a whole chapter of wonderful escapes. One shell burst within ten feet of me, throwing me flat by its concussion and covering me with dirt. As I was trying to eat a little breakfast, a rifle bullet struck the board on which was my plate, and sent things flying; but it seemed that my time to be hit had not come.”

—Charles Fessenden Morse, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, on close calls he had during the Atlanta Campaign, in a letter home, July 31, 1864

“The wounded are at the hospital and the sad thought comes, nothing has been accomplished by all this loss. A soldier showed me his hat where a ball had been shot through it; he said if a man dodged a ball he was sure to get ‘hit.’”

—Henry Warren Howe, 30th Massachusetts Infantry, on the aftermath of the Battle of Big Bethel, in his diary, June 10, 1861

“[W]hile we were waiting … [to advance] the enemy opened on us from the fortress with heavy guns, firing every conceivable thing they could get into them—pieces of railroad iron, old horseshoes, nails, spikes, etc.—but they flew harmlessly over our heads. A bullet flew uncomfortably near me and wounded a man directly in my rear. It hit his leg, and I heard the bones crash.”

—George G. Smith, 1st Louisiana Infantry (Union), on the Siege of Port Hudson, in his diary, June 14, 1863

“Yesterday … my division … was in the thickest of it. I was hit by a spent grape-shot, giving me a severe contusion on the right thigh, but not breaking the skin. Baldy was shot through the neck, but will get over it. A cavalry horse I mounted afterwards was shot in the flank.”

—Union general George Gordon Meade, on his—and his horse, Baldy’s—experience at the Battle of Antietam, in a letter to his wife, September 18, 1862

“Shells began to drop all around us. Finally one came in our midst, doing much damage, some being killed and wounded. It caused great excitement as the dust and dirt flew over us. A peculiar numbness came to me, making me think I was wounded. Picking up my gun that had fallen to the ground, I discovered that it had been hit by a piece of the exploded shell, the barrel being flat and bent. I threw it down and picked up another on the field. That was no doubt the cause of my numbness.”

—Charles H. Lynch, 18th Connecticut Infantry, on the Battle of Kernstown, in his diary, July 24, 1864

“Fighting is still going on at the front, and we are expecting every moment to go in again. We have been for eight days on the front line of battle…. [W]e have … fought where we could not raise our heads above our works without being shot at. Many a rebel bullet has whistled past my head so near, I could almost feel the wind of it! I have no time to tell of narrow escapes; ‘suffice it to say,’ you yet have a husband and our little boy a father, with an unshattered mind and body.”

—Charles De Mott, 1st New York Artillery, in an undated letter to his wife about the Battle of the Wilderness. De Mott was killed weeks later, on June 3, 1864, at the Battle of Cold Harbor.

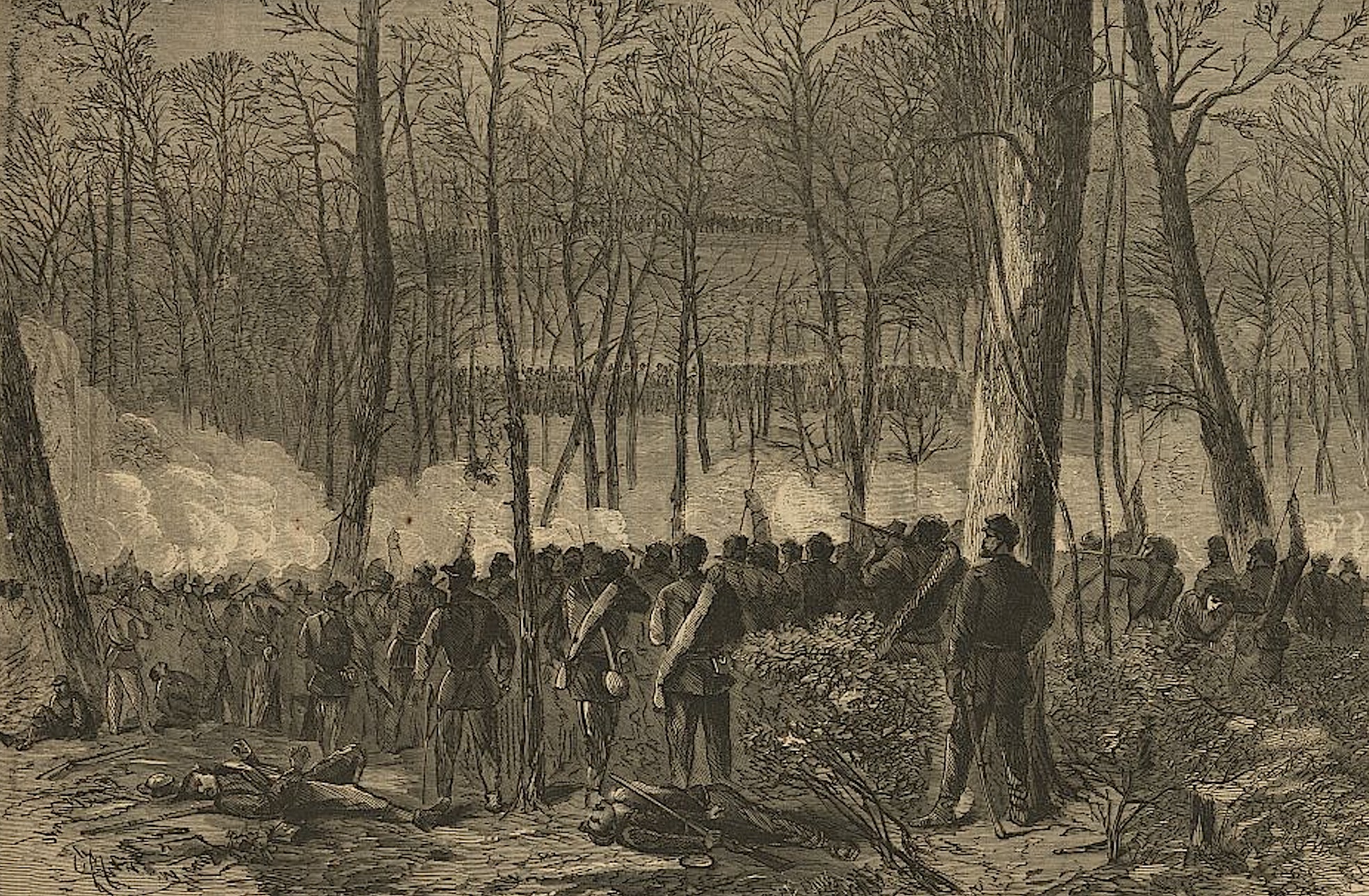

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyUnion and Confederate soldiers exchange fire during the Battle of the Wilderness.

“[T]he enemy suddenly opened on us from two batteries planted about 500 yards from our right flank, in the edge of the woods. These batteries enfiladed us, and such another dose of shot and shell I have never experienced. We sent our horses in the rear in time to save them, and got close to the works. The missiles fell high and low around and amongst us. We lost many officers and men from this hot fire. I expected my time had come, but I was protected by a merciful Providence.”

—Union officer J.T. Conolly, in a letter to a friend about an incident during the Siege of Petersburg, August 1864

“They … almost immediately saw us, and gave chase. My old horse could not make time enough; and their bullets whistled merrily around us, as we lay down on our horses’ necks, and fairly sailed through the trees. I found their horses had the speed on me; and, watching my chance, I slid off the saddle into the bushes, and let the horse go on. He went; and, as I found out afterwards, a bullet just grazed his neck, which would have settled me, had I been in the saddle.”

—Lieutenant William M. McLain, 32nd Ohio Infantry, on his and a comrade’s encountering a squad of Confederate cavalry while on a reconnaissance mission during the Union advance toward Atlanta, in a letter to a friend, June 28, 1864

“We watched them till they were all ready, and with the first flash from their guns, we dodged down behind our breastworks—not a second too soon, for the first shell came directly over our company, and striking a post, burst into a thousand pieces, throwing sand and splinters all over us. No one was hurt, which was a great wonder.”

—Union soldier John E. Whipple, in a letter about receiving enemy artillery fire at the Battle of New Bern, North Carolina, March 14, 1862

“Such a gauntlet I hope I may never be called upon to run again. It was, in imagination at least, like being blown from the mouth of a cannon, they were so near; and yet, through providential grace, this proved our salvation, for rifles over-carry at short range, and we were so high above them that we all escaped unharmed, though with bullet holes through the clothes of some of the men.”

—Captain Rowland Minturn Hall, 3rd New York Cavalry, in an undated letter about a hazardous reconnaissance mission he and some comrades undertook during the Battle of Goldsborough Bridge, North Carolina, in December 1862

“Our company lost one killed and ten wounded, and how I escaped is a wonder to me. Men were falling on every side, and the carnage was becoming too terrible for mortal to withstand, when we were ordered to ‘fall back,’ which we did in good order.”

—Sergeant T.A. Rollins, 95th Illinois Infantry, on the fighting during the Siege of Vicksburg, in a letter to his mother, May 22, 1863

Library of Congress

Library of Congress“Siege of Vicksburg” by Thure de Thulstrup

“It was a terrific fight … and it is wonderful how we all got off so well. A round shot killed one of our men not far from me, and another cut a spoke out of a wheel by which I was standing with my foot on the hub.”

—Confederate artillerist Alexander R. Boteler Jr. on the Battle of Kernstown, in a letter to the Augusta Weekly Chronicle & Sentinel, March 26, 1862

“One shot passed near me wounding a man just behind me, another came within two inches of my head, striking the bank and throwing the dirt in my face, pretty close, I thought, as I tucked my head a little lower. The Yankees had some splendid marksmen there.”

—J.D. Bethune, 2nd Georgia Infantry, on taking fire while serving in Confederate trenches at Dam No. 1 during the Peninsula Campaign, in a letter to the Columbus Sun, May 31, 1862

“Men fell on every side of me, but by an unaccountable provision of Providence I remained untouched.”

—Edgar Thompson, 28th Georgia Infantry, on the Battle of Seven Pines, in a letter to his father, June 1, 1862

“One fellow was so imprudent in coming out and firing at our boys, that I could not restrain my desire to teach him a lesson in prudence. Procuring a good rifle, and getting a good opportunity, I leveled away at him. The effect was to provoke him the more, and for my two shots I received three, which came near as was pleasant I assure you.”

—Lieutenant Virgil A.S. Parks, 17th Georgia Infantry, on exchanging fire with an enemy picket during the Peninsula Campaign, in a letter to the Savannah Republican, June 14, 1862

“I was knocked down by a spent grape shot, which struck me on the neck, and now have rather a stiff neck from it; had it been an inch higher it would have fractured my skull, or had it been with more force it would have taken my head off. I was also struck by a spent minie ball on the ankle, which stung considerably for a time; but it is all right now.”

—J.B. Moore, 17th Georgia Infantry, on the Battle of Second Manassas, in a letter to his mother, August 31, 1862

“I was so completely exhausted when the battle ended, that I could scarcely walk; but I made an effort to get up the mountain, while they were shooting at me from three different directions; but fortunately, they did not kill me, though my haversack was shot from off my back, and balls grazed a hand and leg. After walking some fifty yards I surrendered.”

—Georgia soldier Marcus Oliphant, on the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam, in an undated letter published on October 28, 1862, in the Augusta Weekly Chronicle & Sentinel

“I had on a pair of old boots which were bursted to pieces. A rock got into the toe of one of them and hurt me so badly I had to stop to get it out. I had not more than got fixed to start again till a cannon ball passed in a few inches of my head and struck the middle of the road…. Although the ball did not touch me it knocked me down and filled my eyes with dirt and gravel. I lay on the ground senseless for a few minutes and rose to my feet with a ringing in my ears I shall never forget.”

—R.A. Gaines, 18th Georgia Infantry, on the Battle of South Mountain, in a letter to his brother, October 11, 1862

“One of our company was shot through the brim of his hat, the piece of shell passing down in front of him and into his blankets. Another piece of shell struck one of our men’s haversack, and fell inside.”

—An anonymous Confederate soldier, in a letter about the Battle of Chancellorsville to Georgia newspaper Columbus Sun, May 5, 1863

“I was struck twice, though both times was only grazed; one time on the wrist of the right arm, by a rifle ball barely breaking the skin. I saw the fellow when he shot at me. A small piece of shell struck me on the right arm near the shoulder, and went deep enough to lodge. I got one of the boys to cut it out with his knife while the fight was going on.”

—Micajah D. Martin, 2nd Georgia Battalion, on the Battle of Chancellorsville, in a letter to his parents, May 8, 1862. He added, “Neither shot disabled me, and I have kept my place ever since.”

“As we advanced … the minie balls and grape shot came like hail…. [M]y gun was cut partly in two by a piece of shell, and a fragment passed through my coat sleeve.”

—An anonymous soldier in the 2nd Georgia Battalion, in a letter about the Battle of Chancellorsville to his father, May 10, 1863

Sources: Personal Recollections and Civil War Diary, 1864 (1908); My Cave Life in Vicksburg (1864); The Siege of Vicksburg (1915); Under the Guns (1895); Richmond During the War (1867); Army Letters, 1861–1865 (1903); War Diary and Letters of Diary of Stephen Minot Weld (1912); The Diary of a Line Officer (1906); A Texan in Search of a Fight (1901); Army Life from a Soldier’s Journal (1886); Soldiers’ Letters, From Camp, Battle-Field and Prison (1865); Phil Koempel’s Diary (1920); Letters Written During the Civil War (1898); Passages from the Life of Henry Warren Howe (1899); Leaves from a Soldier’s Diary (1906); Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, Volume 1 (1913); The Civil War Diary, 1862–1865, of Charles H. Lynch (1915); William B. Styple, ed., Writing & Fighting from the Army of Northern Virginia (2003).