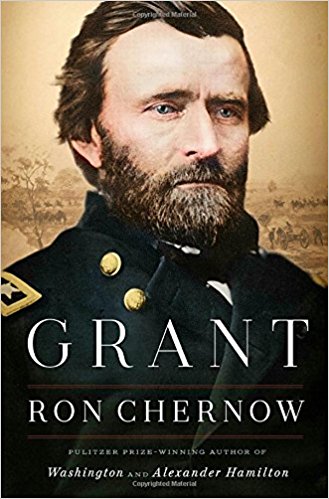

Grant by Ron Chernow. Penguin Press, 2017. Cloth, IBSN: 978-1594204876. $40.00.

The standard interpretation of Ulysses S. Grant’s life usually recounts an undistinguished West Point and antebellum army career ended by alcohol abuse, followed by a meteoric rise in rank and responsibility during the Civil War, followed by a failed presidency riddled by scandal and then a triumphant memoir written while he was dying. While some historians have perpetuated the idea of Grant as an unfeeling “butcher” during the Civil War—especially as Union forces slugged it out against Robert E. Lee’s Confederates during the war’s final year—most have revered Grant’s military prowess and given him his due for his central role in ending the war. Until recently, though, few have taken a serious look at Grant’s postwar life and presidency or offered a reassessment that enhances Grant’s standing as a civilian leader. Ron Chernow’s massive new biography, Grant, does just this and is a far more valuable contribution to understanding Grant after the war than during it.

The standard interpretation of Ulysses S. Grant’s life usually recounts an undistinguished West Point and antebellum army career ended by alcohol abuse, followed by a meteoric rise in rank and responsibility during the Civil War, followed by a failed presidency riddled by scandal and then a triumphant memoir written while he was dying. While some historians have perpetuated the idea of Grant as an unfeeling “butcher” during the Civil War—especially as Union forces slugged it out against Robert E. Lee’s Confederates during the war’s final year—most have revered Grant’s military prowess and given him his due for his central role in ending the war. Until recently, though, few have taken a serious look at Grant’s postwar life and presidency or offered a reassessment that enhances Grant’s standing as a civilian leader. Ron Chernow’s massive new biography, Grant, does just this and is a far more valuable contribution to understanding Grant after the war than during it.

Though his background is in journalism rather than history, Chernow has gained a reputation for well-written, lengthy biographies of important figures in American history. You probably know him for his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of George Washington, or his renowned Alexander Hamilton, the book that served as the basis for Lin-Manuel Miranda’s popular musical Hamilton. Grant will certainly add to his standing as one of the nation’s most prominent (and verbose) contemporary biographers.

Chernow shows us a young Ulysses S. Grant whose mother, Hannah, was detached and unaffectionate and whose father, Jesse, loomed large as his son’s fame and influence grew during the Civil War and then as president. The father was always quick to try to capitalize on his son’s name, both for himself and for relatives and friends. One thing young Ulysses did get from his father—and that Chernow masterfully examines in the book—was a dislike for the institution of slavery. Grant possessed an inherent sense of fairness that made him view slavery as an immoral institution, and this feeling stayed with him through the war and his presidency. It also made his life difficult when he married Julia Dent, whose father was a staunch Democrat and slave owner. While Julia proved a devoted wife and wonderful partner for Grant, his relations with his father-in-law were never overly cordial.

As anyone with even a passing knowledge of Grant’s life knows, alcohol played a large and detrimental role in it. Chernow seems to have made it his mission to once and for all answer the questions about Grant’s history with liquor. There is no doubt that alcohol abuse was the reason Grant left the army in 1854. In Chernow’s telling, Grant was an alcoholic, and he knew it and acknowledged it to others. He overcame the addiction through willpower and with the help of his wife, who ensured her husband avoided temptation when she was with him. During the Civil War years, when he was away from Julia for extended periods, he tasked members of his military staff, particularly his friend John Rawlins, with keeping him sober. By the end of the Civil War and certainly by the time Grant was president, he had conquered his addiction and lived the rest of his life with few minor relapses. With this, alcohol—practically a main character in much of the book—is barely mentioned again.

The real value of Chernow’s Grant comes when the author turns his sharp research and writing skills toward Grant’s two terms (1869–1877) as the eighteenth President of the United States. While traditionally viewed as a failure as president, Chernow (along with other recent historians) convincingly argues that Grant was a far better chief executive than often thought. He was dedicated to ensuring the rights, freedoms, and safety of African Americans, and his administration vigorously pursued indictments against members of the Ku Klux Klan. That inherent sense of fairness, the lessons he learned during some of his own life’s lowest periods, and his experiences with black troops during the Civil War all combined to make Grant a dedicated ally to former slaves in the South. Chernow quotes Frederick Douglass as noting that, “To Grant more than any other man the Negro owes his enfranchisement…. In the matter of the protection of the freedman from violence his moral courage surpassed that of his party.”

Chernow also shows the reader that Grant could be almost painfully naïve when judging people. As a friend he was loyal to a fault, even to many that no longer deserved his friendship or good graces. While we see that President Grant was personally honest and dedicated to running an efficient, ethical administration, his choices of close advisers and cabinet officers did not always serve him well. Many of the scandals that past historians have used to judge Grant’s presidency a failure—the “Whiskey Ring” and others—resulted from others taking advantage of their positions and their relationships with Grant, who was often slow to act when disciplining or firing a friend was required. After his presidency, his blind faith in young financier Ferdinand Ward cost him every dime he had.

While Chernow’s books is certainly not perfect—for example, he pays little attention to events in the West—Grant is definitely an accomplishment that belongs on the reading lists of those interested in the Civil War as well as students of American politics and the presidency. This book will be one that future scholars look at as they reassess Grant’s political career, and if his presidential ranking continues to rise, there is little question that Ron Chernow’s exhaustive research and accessible writing style will be part of the reason.

Todd Arrington is Site Manager of the James A. Garfield National Historic Site in Mentor, Ohio. His history of the presidential election of 1880 will appear next year from the University Press of Kansas.