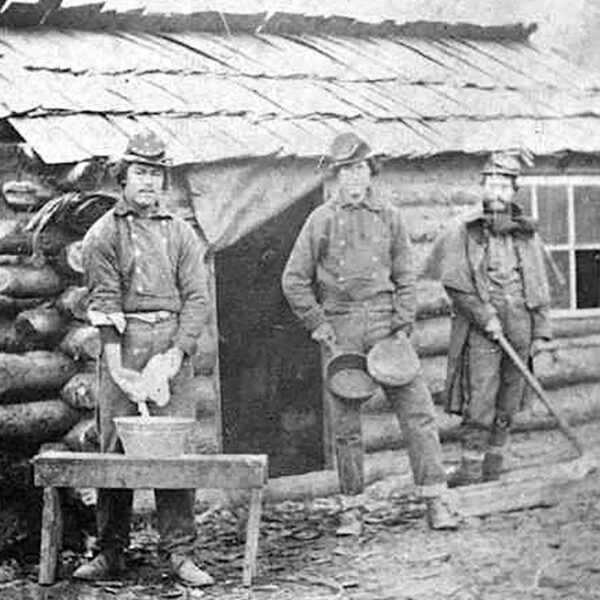

Library of Congress

Library of CongressCivil War nurse Anna Bell Stubbs helps care for ailing Union soldiers at a Nashville hospital during the conflict.

It’s well-known that the Civil War was the United States’ deadliest conflict. Between 750,000 and 1 million Americans died, shockingly high figures that still drive interest in the conflict more than a century and half later. It’s also recognized that about two-thirds of those deaths were from disease. Out of 6.5 million reported cases of sickness and injury among 3.2 million Civil War combatants, only about 500,000 reports represented battle wounds or accidental injuries—roughly half of them gunshot wounds.

That much sickness shocked witnesses and badly overstretched the health care systems. As a medical historian, I can’t help but wonder how wartime Americans experienced this health catastrophe and dealt with the fallout. What caused so much sickness? Why did so many soldiers and refugees take ill then succumb? And what were the legacies of all this suffering?

In future installments of this column, I will explore the fascinating and surprising ways the Civil War transformed American medicine. Far from being in a “medical Middle Ages” of butchery and squalor, surgeons developed game-changing innovations to combat sickness in the ranks and help wounded survivors recover during and after the war. Bullet-biting amputations were far less common than scientific solutions like vaccines and the use of microscopes and hypodermic syringes.

Of course, before we can begin to understand those medical innovations, we need to understand why so many people became ill and died.

The Civil War triggered an unprecedented explosion of deadly epidemics that far eclipsed anything seen by Americans before the war. Smallpox, typhoid, dysentery, and measles ravaged not only sick soldiers, but also emancipated slaves and hungry refugees. Between disease and war wounds, about 3 percent of the U.S. population died. In comparison, it would take nearly 10 million COVID-19 deaths for the country to reach the Civil War’s mortality rate today.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUnion soldier-patients convelesce in Harewood Hospital, Washington, D.C., during the Civil War.

Why did these epidemics become so severe? The war occurred before microbes were well understood and before the development of vaccines for most of what today are considered “childhood” illnesses. When armies mobilized and marched, those many thousands of people carried microbes with them, triggering epidemics as pathogens found new hosts. Most rural Americans had limited exposure to or had no acquired immunity from infectious diseases. When young recruits mobilized in 1861–1862, millions of men without immunity to smallpox and measles crowded into training camps and transport ships. The same was true of refugees from slavery who congregated in pop-up camps near the front lines.

Suddenly exposed to opportunistic and unfamiliar microbes, huge disease outbreaks followed, felling entire units. Civil War commanders tried to “season” new recruits in special camps, where they contracted and (it was hoped) recovered from measles before shipping out. Men with smallpox were isolated in special hospital wards and physicians tried to vaccinate others to eradicate the disease in the army. By the war’s midpoint, epidemic measles among soldiers had largely subsided, but smallpox continued to rage largely unchecked among refugees.

During campaign season and in winter camps, dysentery and typhoid fever presented ever-constant threats. Both diseases were spread by feces-contaminated water, and typhoid also spread through contaminated food. Army camps often lacked groundwater drainage and trash removal, and overcrowded tents were too close together. Most camps had open-air latrines just a few feet from sleeping, cooking, and eating areas. Weary soldiers often defecated close to camp, contaminating their water supplies. Hands went unwashed and food went undercooked. Consequently, “divers miseries in the bowels” were omnipresent among soldiers, according to one Confederate surgeon. At Andersonville prison camp, Union soldiers had no water supply but a stream infected by feces from a Confederate camp not far away. The prison’s latrines, located just a few yards from tent rows, also contaminated the groundwater. Confederates withheld medical care. Thirteen thousand men, a quarter of Andersonville’s prisoners, died from dysentery, typhoid, and “chronic diarrhea.”

Even though they were not yet aware of the microbes behind these epidemics, health care workers felt the urgent need to act. Many observers realized that poor sanitation played a role in spreading dysentery and typhoid. The United States Sanitary Commission famously strived to convince commanders and soldiers to clean up communal spaces. Agents tried to get latrines relocated away from camps and to build well-ventilated hospital wards, saving many lives. After the war, physicians and medical volunteers returned home, spreading the message that sanitation could prevent epidemics. Newly established boards of health in cities like Chicago and New York tried to clean up filthy rivers, drain standing puddles, and enforce quarantines. Cholera and yellow fever deaths plummeted in the postwar decades.

But such efforts did not totally resolve the war’s health crisis. For every convert to cleanliness, there was a tired soldier or busy commander who remained unmoved by the Sanitary Commission’s health advice. Epidemics among the formerly enslaved, and even among black troops fighting for freedom, went unreported and unmitigated. As the war dragged on, medical officers and volunteers found themselves fighting an increasingly dire health crisis. Yet amazingly, they did not lose hope, instead responding with scientific investigations that unlocked new therapeutic interventions and new ways of understanding sickness.

Read along in future columns as we explore those innovative advances of Civil War medicine, from miracle painkillers to vaccines and microbe-hunting devices.

Jonathan S. Jones is an assistant professor of history at James Madison University. His research explores the medical and social legacies of the Civil War among veterans, their families, and doctors.