Library of Congress

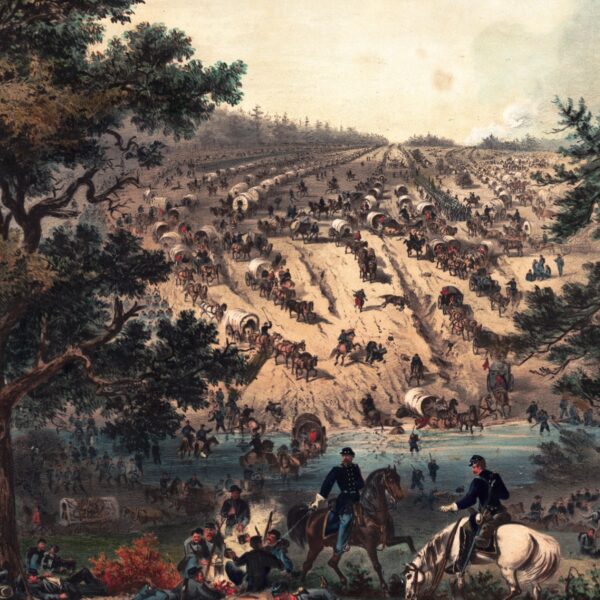

Library of CongressUnion troops advance during the Battle of Fredericksburg.

In its February 7, 1863, issue, Harper’s Weekly published the following poem. Titled “At Fredericksburg” and published under the byline “L.C.M.,” the poem tells a poignant tale of two Union army comrades swept up in the Battle of Fredericksburg, a decisive and demoralizing defeat for Ambrose Burnside’s Army of the Potomac fought on December 11–15, 1862. On December 13, repeated waves of Union regiments had advanced up the slopes of Marye’s Heights west of the city against intrenched Confederates from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Over 12,000 Union soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured during the ensuing struggle. L.C.M.’s poem is reproduced below, in full:

It was just before the last fierce charge,

When two soldiers drew their rein,

For a parting word and a touch of hands—

They might never meet again.

One had blue eyes and clustering curls—

Nineteen but a month ago—

Down on his chin, red on his cheek:

He was only a boy, you know.

The other was dark, and stern, and proud;

If his faith in the world was dim,

He only trusted the more in those

Who were all the world to him.

They had ridden together in many a raid.

They had marched for many a mile,

And ever till now they had met the foe

With a calm and hopeful smile.

But now they looked in each other’s eyes

With an awful ghastly gloom,

And the tall dark man was the first to speak:

“Charlie, my hour has come.

“We shall ride together up the hill,

And you will ride back alone;

Promise a little trouble to take

For me when I am gone.

“You will find a face upon my breast—

I shall wear it into the fight—

With soft blue eyes, and sunny curls,

And a smile like morning light.

“Like morning light was her love to me;

It gladdened a lonely life,

And little I cared for the frowns of fate

When she promised to be my wife.

“Write to her, Charlie, when I am gone,

And send back the fair, fond face;

Tell her tenderly how I died,

And where is my resting-place.

“Tell her my soul will wait for hers,

In the border-land between

The earth and heaven, until she comes;

It will not be long, I ween.”

Anne SK Brown Military Collection

Anne SK Brown Military CollectionUnion soldiers advance up Marye’s Heights during the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Tears dimmed the blue eyes of the boy—

His voice was low with pain:

“I will do your bidding, comrade mine,

If I ride back again.

“But if you come back, and I am dead,

You must do as much for me:

My mother at home must hear the news—

Oh, write to her tenderly.

“One after another those she loved

She has buried, husband and son;

I was the last. When my country called,

She kissed me and sent me on.

“She has prayed at home, like a waiting saint,

With her fond face white with woe:

Her heart will be broken when I am gone:

I shall see her soon, I know.”

Just then the order came to charge—

For an instant hand touched hand,

Eye answered eye; then on they rushed,

That brave, devoted band.

Straight they went toward the crest of the hill,

And the rebels with shot and shell

Plowed rifts of death through their toiling ranks,

And jeered them as they fell.

They turned with a horrible dying yell

From the heights they could not gain,

And the few whom death and doom had spared

Went slowly back again.

But among the dead they left behind

Was the boy with his curling hair,

And the stern dark man who marched by his side

Lay dead beside them there.

There is no one to write to the blue-eyed girl

The words that her lover said;

And the mother who waits for her boy at home

Will but hear that he is dead,

And never can know the last fond thought

That sought to soften her pain,

Until she crosses the River of Death,

And stands by his side again.