Battles and Leaders of the Civil War

Battles and Leaders of the Civil WarA Confederate sharpshooter

What do Union generals John Reynolds, William Sanders, Stephen Weed, and John Sedgwick have in common? According to traditional historiography, each man was killed by a sharpshooter who targeted him, often firing from more than a half-mile away.

This column, the first in a series dedicated to using science and critical reasoning to explore Civil War history, will dissect that legend. The investigation involves the use of basic physics and external ballistics—the science of what happens to a bullet between muzzle and impact—to undo the Civil War myth of the long-distance sniper (a term not even used in the war). Future columns will use other sciences to investigate proposed historical situations: bullets falling like hail (meteorology), battlegrounds that frustrated entrenching or earthworks efforts (geology), panicked soldiers in the heat of combat reloading their muskets a dozen times without ever firing (psychology), rivers running red with blood (hydrology), and battle landscapes that could be crossed afterward only by walking on the dead (geography). In all these cases, science illuminates history, disproving, often in a surprisingly straightforward manner, what books and other texts may have taught us.

Let’s start with the killing of Major General John Sedgwick at Spotsylvania. A review of common military history books and sniper compendiums indicates a consensus about two aspects of Sedgwick’s death: 1) He was walking among the men of his VI Corps, gently scolding them for taking cover from the bullets from a far-off Rebel sharpshooter, one he is said to have claimed was incapable of wounding a pachyderm at such a distance; and 2) he was targeted and killed by a bullet to his skull at a range of at least 900 yards, and perhaps from twice that distance.

Most military historians agree that an extraordinary weapon would be required for such a high-value target at such a great distance. Thus, it is generally understood that a relatively rare weapon from the Confederate arsenal, a Whitworth rifle, would be used.

Whether fired from a rifle or dropped from a hand, a bullet falls because of gravity at a rate of around 32 feet per second2. So one requirement for a rifle capable of accurate fire from a tremendous distance is an exceptionally high bullet velocity—the faster the bullet, the less time it is in the air and falling to earth. Most modern rifles designed for sniper use have a muzzle velocity that approaches 3,500 feet per second. A bullet from such a rifle can cover a half-mile in under a second and, for more realistic targeting, will fall only 24 inches in 400 yards, requiring only a relatively small holdover by the shooter.

With a muzzle velocity of around 1,400 feet per second, a bullet from the Whitworth had the fastest speed and flattest trajectory of any rifle available during the Civil War. It also fired a long, slender “smallbore” slug, which retained more energy (and velocity) downrange because of its elongated and aerodynamic shape. The Whitworth was also demonstrated to be exceptionally accurate. In other words, if you were going to operate as a sniper during the middle of the 19th century, this was the weapon to carry.

To kill a man with a targeted headshot at 800 yards with a Whitworth would, however, require a number of challenges to be satisfied, all at the same time. First, the bullet would be in the air for almost two full seconds, during which time the target had to remain perfectly stationary. Next, because of the parabolic path of the bullet, the shooter would need to aim almost 15 feet over the target’s head and, most importantly, estimate precisely the distance between him and his target. Finally, if there was even the slightest breeze—say, 2 miles per hour—the shooter would have to adjust for the wind direction and speed. Also, at a distance of a half-mile, the general would appear to be the same size as the period at the end of this sentence.

If the sniper calculates that his target is 2,400 feet away, but in actuality he is only the slightest bit farther at 2,440 feet, the bullet sprays dirt on Sedgwick’s boots. If the shooter overestimates the distance by a mere 10 feet, the round sails over his target’s head. If the wind is blowing 2 mph faster downrange than where he is firing from, or from a slightly different direction, he misses. If Sedgwick moves in any direction during the two seconds after firing, the bullet falls harmlessly. In short, for a bullet from such a reputed distance to have felled Sedgwick on May 9, 1864, the shooter needed to aim precisely 13.8 feet above and 10 inches behind the momentarily frozen general, all after estimating his range with 98.4% accuracy. That did not happen.

Courtesy of the author

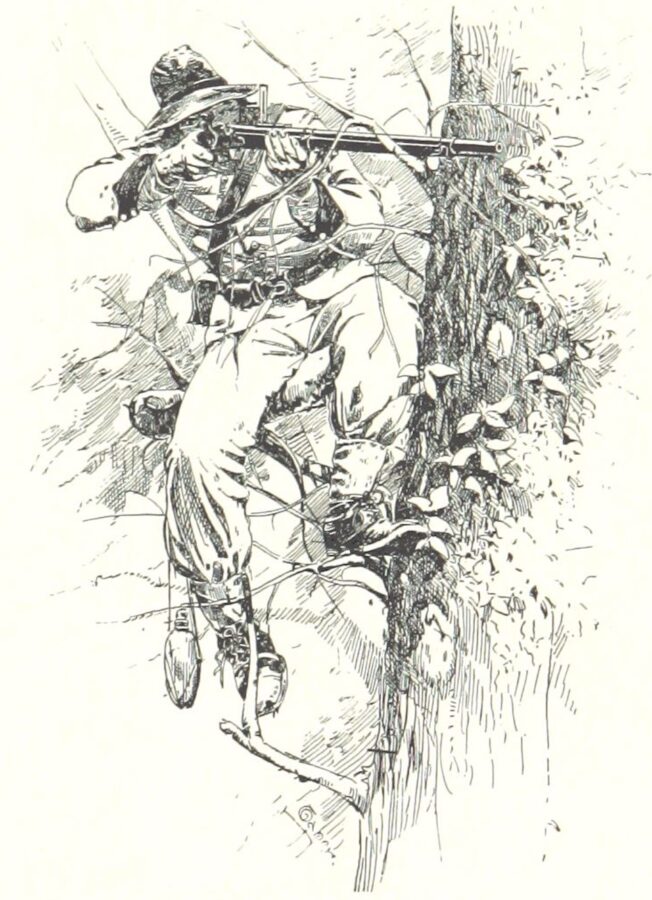

Courtesy of the authorThe monument to the 140th New York Infantry at Gettysburg stands over 8 feet high and includes a bronze relief of Colonel Patrick H. O’Rorke, one of the few Federal officers killed on the crest of Little Round Top by something other than sharpshooter fire. On the right is the same monument viewed through a modern Leupold rifle scope at 4X magnification, photographed from the famous “sniper’s den” in Devil’s Den. The crosshairs are positioned to strike O’Rorke using a holdover for a modern sniper rifle; with a Civil War weapon, the bullet would have fallen more than 50 feet below the monument on the side of the hill (approximately where a dark boulder intersects with the vertical crosshair). Hazlet and Weed were killed where a group of tourists are gathered on the left of the telescopic view. A person in red walks just to the left of the monument and provides a sense of the sharpshooter’s degree of difficulty at such a distance, especially without a rifle scope. (Note: The author did not bring a high-powered sniper rifle onto the Gettysburg Battlefield, only a scope and a camera.)

Gettysburg is the battle most written about in history, and most detailed volumes convey an even more impressive sniper story from Little Round Top. A Confederate sharpshooter, positioned in Devil’s Den, hit Brigadier General Stephen Weed from about 550 yards away. When Lieutenant Charles Hazlet rushed to take in the mortally wounded commander’s last words, he too was cut down by the marksman. Astonishing—two consecutive shots, at a 5 degree angle uphill, from more than 500 yards away, with a rifle musket.

Now let us determine the probability of success for this scenario. First, assume the shooter is armed with one of the more accurate types of rifle musket available to the Rebel infantry, a British Enfield. Despite this rifle’s reputation for precision, tests during the war (and more recently) reveal that it is only capable of hitting a human-sized target at a distance of 500 yards about 50% of the time. That means that for two consecutive shots, the probability of success falls to 25%, even if aimed perfectly at the targets. The shooter’s skill has nothing to do with the 75% chance of a miss; it is simply the result of the inherent inaccuracy of his weapon at this great distance.

With a muzzle velocity of around 900–950 feet per second propelling a broad, much less aerodynamic minie ball, the round will be in the air for two full seconds and the sharpshooter must aim 17 feet over the target. And there cannot be any wind (on a Pennsylvania hilltop in midsummer), and both targets must remain perfectly still during the four seconds the bullets are in the air. And, once again, this historical sniper must know the distance to his targets within a dozen feet (at 550 yards). The story as long told simply had no scientific underpinnings.

Most sharpshooters during the Civil War were selected because they were gifted marksmen who usually operated as elite skirmishers. Distant shots were occasionally successful, often taken from longer than 100 yards, but these soldiers were not operating as snipers as we think of them on modern battlefields. The term “sniper” only gained popularity much later in World War I.

For decades Civil War writers and interpreters have been relating sniper stories in a manner that would have the Whitworths, Springfields, and Enfields performing with the ballistics of a modern high-power rifle. Instead, those weapons had the muzzle velocity and bullet shape of a 9 mm handgun, a weapon that, even with a preposterously long barrel, would be a ludicrous choice for a 400-yard shot. What is much more probable is that these unfortunate generals were cut down by area fire—a sharpshooter was aiming in the general vicinity of the general, hoping an exceptionally auspicious shot might strike a high-value target. People dislike the notion of a person of importance being killed in an unimpressive manner (to this day we struggle with the Cold War-era scenario in which a beloved president is ambushed by an unimportant person wielding a military surplus gun). As a result, our legendary stories from that time about remarkable long-range killings by the sharpest of shooters persist, if for no other reason than that the concepts of area-fire and lucky strikes are so much less impressive.

Scott Hippensteel is professor of earth sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he focuses on coastal geology, geoarchaeology, and environmental micropaleontology. He has written three books about using science to illuminate military history: Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat (University of Georgia Press, 2023), Myths of the Civil War: The Fact, Fiction, and Science behind the Civil War’s Most-Told Stories (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), and Rocks and Rifles: The Influence of Geology on Combat and Tactics during the American Civil War (Spring Nature, 2018).