“The Saltpeter is the Soule, the Sulphur is the Life, and the Coales the Body of it.”

— John Bate, The Mysteryes of Nature and Art (1634)

If cannon and rifles were the engines of war, then gunpowder was the fuel for those engines. On countless Civil War battlefields, the fuel was employed to great effect—physically and psychologically—just as it had for the centuries prior. When Francis Bacon declared that “Printing, gunpowder, and the magnet…these three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world,” he gave testament to the fact that the influence of gunpowder in history cannot be underestimated.1

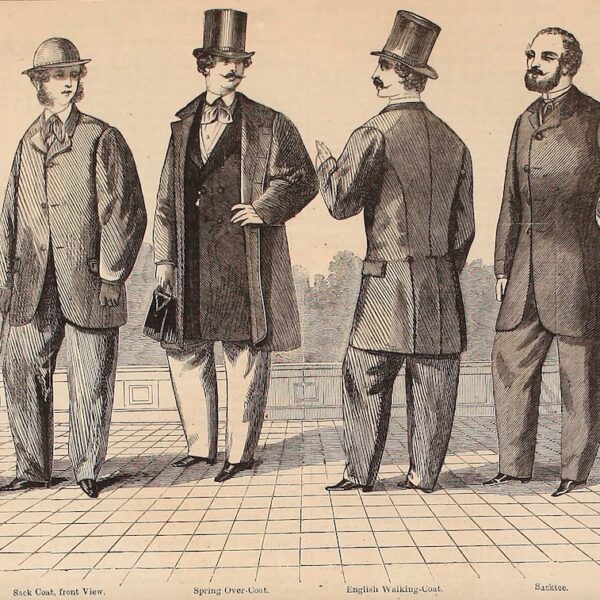

No one knows exactly when gunpowder was invented; one author suggested that anyone looking into its genesis “is soon entangled in a web of mistakes, misinterpretations and misrepresentations.” Its origins have been traced to Egypt, Persia, India, and Arabia. More recently, scholarship suggests that its birth occurred in China in the mid-ninth century A.D. Gunpowder was first used in fireworks, but it did not take long to see it used in simple ordnance. As elusive as the invention’s provenance is its transfer to the West. An early work, attributed to “Mark the Greek,” had the recipe and a perverse title: Book of Fires for the Burning of Enemies.2 However, it was revealed that the recipe—which did not change for centuries—is actually quite simple; it is the combination of three ingredients: saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal in a ratio of approximately 75%, 10%, and 15%, respectively (although early samples contained much smaller amounts of saltpeter), finely powdered, and mixed well.

Given the immense amount of gunpowder used during any large scale conflict, securing the “Soule, Life, and Body” was, not unexpectedly, an important consideration for the authorities of both belligerents during the American Civil War. The New York Times felt so confident in the Union’s supply of gunpowder that it proudly proclaimed in August 1861 that “We have more than enough already to drive a bullet to the heart of every traitor that breathes in our land.” There was reason to be confident: when the war broke out, the North was home to more than fifty powder mills; the South, in contrast, only a handful. However, most of the mills in the North were small; many were in the mining regions of Pennsylvania, producing crude blasting powder for local use only. Thus, the Times’ confidence would ultimately prove to be hasty.3

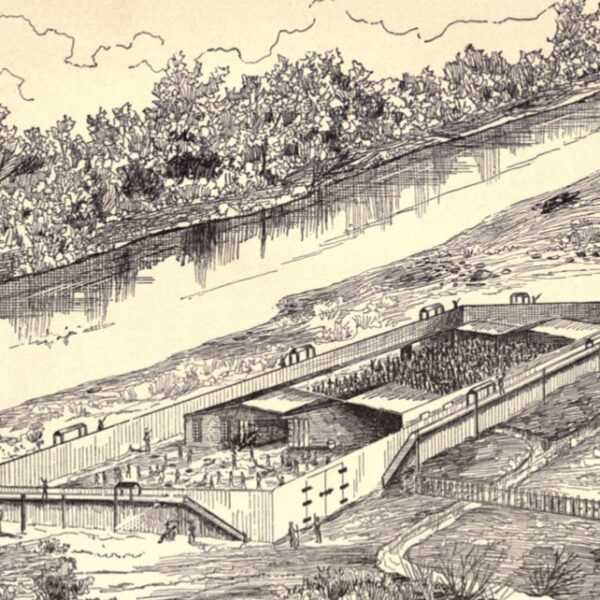

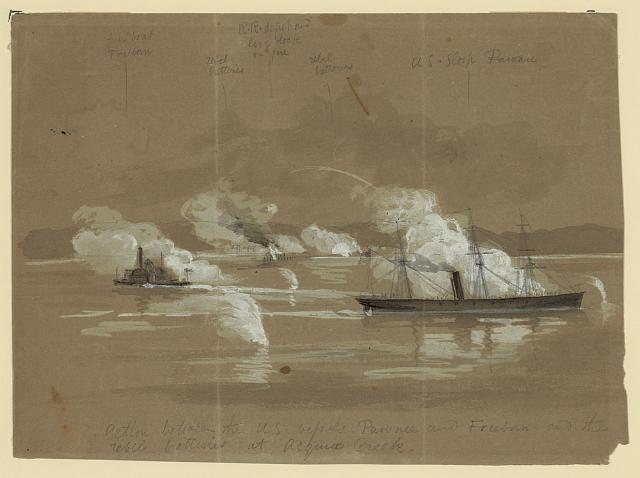

The chief producer of black powder, itself responsible for nearly forty percent of the country’s production in 1860, was E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, located on the Brandywine River near Wilmington, Delaware. The role of the du Pont mills during the American Civil War is grand in its scope: keeping powder out of enemy hands, protecting itself from marauding enemies, supplying the immense needs of the Union Army and Navy, participating in secret missions, and more. The company boasted authentic family heroes at sea, on land, and as powdermen who gave the ultimate sacrifice by simply doing their job.4

Fortunately, for historians, few American companies have maintained their historical records as well as du Pont. The collected business papers of the company and the personal records of the family form the core of the Hagley Museum and Library, which sits on the original powder works property on the Brandywine. Though dated, John Beverly Riggs’s A Guide to the Manuscripts in the Eleutherian Mills Historical Library (Greenville, DE: Library, 1970; supplement published in 1978) remains an essential starting point for the huge amount of material. Inventories and finding aids are available online through the library’s website and should be an important resource for Civil War scholars. Among the more interesting Civil War-related documents in the collection are ones that make us look beyond the obvious wartime uses of black powder. Peacetime enterprises that relied on powder for blasting—the mining of gold and coal—also became important in supporting the war effort. For example, the successes of Confederate sea raiders prompted an increase in insurance rates and a tightening of permission to ship powder to California. A du Pont powder agent warned that if gold miners were not adequately supplied with powder, shipments of bullion to the East would be cut in half and that the effect of such a reduction to the country’s currency would be “greater than would be experienced by the loss of a dozen battles.”5 A similar warning came from a du Pont agent in Cincinnati anxious to keep his coal-mining customers in powder as well:

We have your letter of the 13th inst. We regret very much that the mining powder cannot be sent as usual. We have not a single keg on hand now. There is none to be had in this part of the country and if we must wait for it to come by canal, the wait will be disastrous.Coal cannot be mined without powder and the naval fleet on the Ohio and Mississippi will be powerless unless they can get coal for the boats. They have to rely entirely on the supplies furnished by the mines we want this powder for and at best the supply of coal is altogether scant and it sells here today at three times the price usually current. If this explanation was made to the authorities at Philadelphia they might make a special exemption in this case. Cutting off the supply of coal from the fleet would be the very best kind of assistance to the rebels. Coal for the Furnaces is as important as Gunpowder for the Guns.6

James M. Schmidt is the author or editor of three books on the Civil War. He is a biotech research scientist near Houston, Texas, and blogs at Civil War Medicine.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Notes:

1 J. Kelly, Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. New York: Basic Books, 2004, p. ix.

2 G.I. Brown, The Big Bang: A History of Explosives. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton, 1998, p. 4.

3 New York Times, August 10, 1861, p. 3.

4 The convention for spelling the family name is “du Pont” when quoting an individual’s full name but “Du Pont” when speaking of the family as a whole (and for some individuals, most notably Civil War naval hero Samuel Francis Du Pont). The name of the chemical company founded by the family is properly spelled DuPont. For simplicity, I have used “du Pont” throughout this post.

5 H. B. Hancock and N. B. Wilkinson. “A Manufacturer in Wartime: Du Pont, 1860-1865.” Business History Review, Vol. 40, Summer 1966, p. 219.

6 J.W. Donohue & Co., Cincinnati, to Messrs. E. I. du Pont & Co., March 18, 1863, Hagley Museum and Library, Accession 500, Series 1, Box 52.