The following is Captain Jesse Taylor’s recollection of the Confederate defense of Fort Henry on February 6, 1862.

…Arriving at the fort, I was convinced by a glance at its surroundings that extraordinarily bad judgment, or worse, had selected the site for its erection. I found it placed on the east bank of the river in a bottom commanded by high hills rising on either side of the river, and within good rifle range. This circumstance was at once reported to the proper military authorities of the State at Nashville, who replied that the selection had been made by competent engineers and with reference to mutual support with Fort Donelson on the Cumberland, twelve miles away; and knowing that the crude ideas of a sailor in the navy concerning fortifications would receive but little consideration when conflicting with those entertained by a “West Pointer,” I resolved quietly to acquiesce, but the accidental observation of a water-mark left on a tree caused me to look carefully for this sign above, below, and in the rear of the fort; and my investigation convinced me that we had a more dangerous force to contend with than the Federals,-namely, the river itself. Inquiry among old residents confirmed my fears that the fort was not only subject to overflow, but that the highest point within it would be-in an ordinary February rise-at least two feet under water. This alarming fact was also communicated to the State authorities, only to evoke the curt notification that the State forces had been transferred to the Confederacy, and that I should apply to General Polk, then in command at Columbus, Ky. This suggestion was at once acted on,-not once only, but with a frequency and urgency commensurate with its seeming importance,-the result being that I was again referred, this time to General A. S. Johnston, who at once dispatched an engineer (Major Jeremy F. Gilmer) to investigate and remedy; but it was now too late to do so effectually, though an effort was made looking to that end, by beginning to fortify the heights on the west bank (Fort Heiman)…

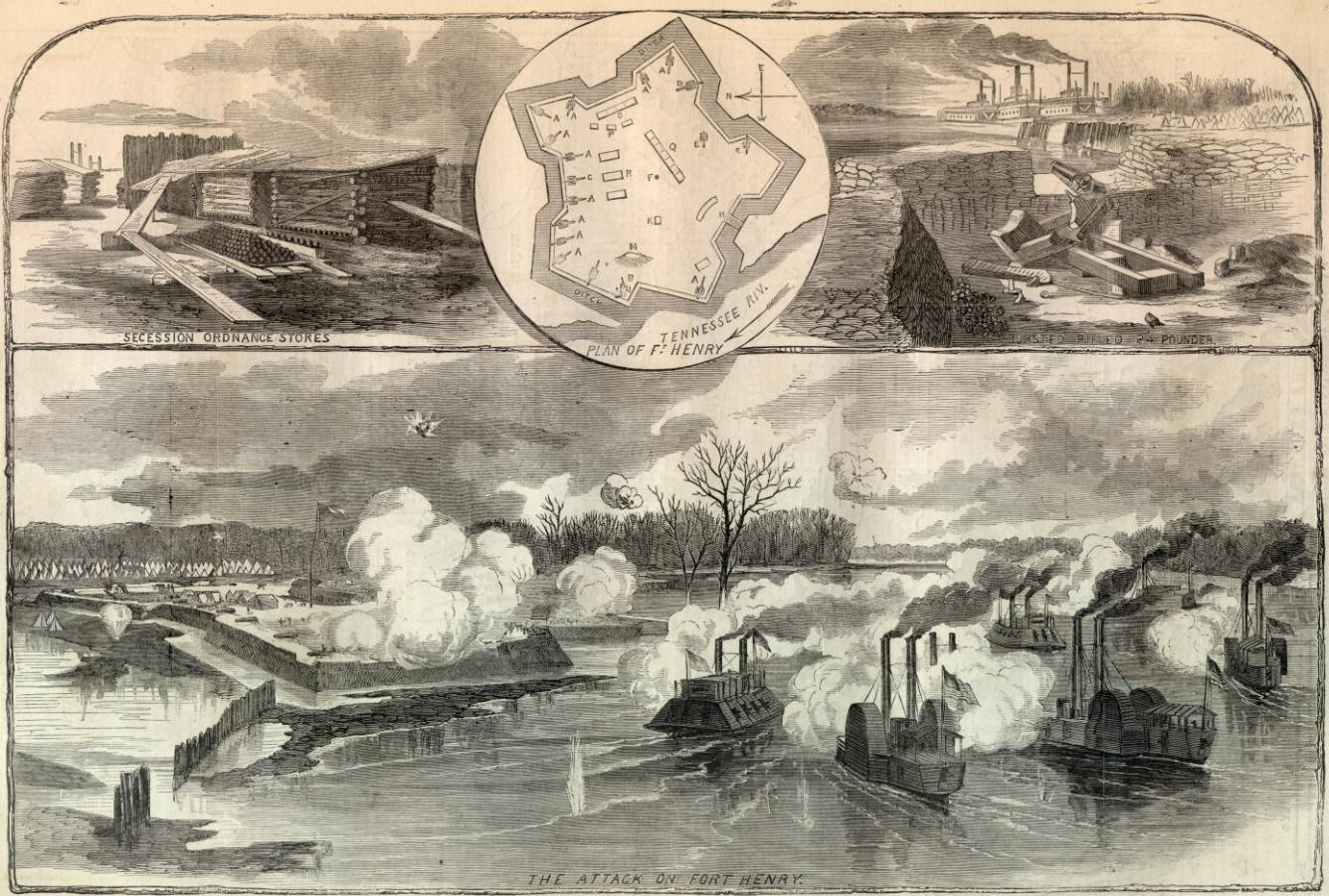

On the 4th of february the Federal fleet of gun-boats, followed by countless transports, appeared below the fort. Far as eye could see, the course of the river could be traced by the dense volumes of smoke issuing from the flotilla-indicating that the long-threatened attempt to break our lines was to be made in earnest. The gunboats took up a position about three miles below and opened a brisk fire, at the same time shelling the woods on the east bank of the river, thus covering the debarkation of their army. The 5th was a day of unwonted animation on the hitherto quiet waters of the Tennessee; all day long the flood-tide of arriving and the ebb of returning transports continued ceaselessly. Late in the afternoon three of the gun-boats, two on the west side and one of the east at the foot of the island, took position and opened a vigorous and well-directed fire, which was received in silence until the killing of one man and the wounding of three provoked an order to open with the Columbiad and the rifle. Six shots were fired in return,-three from each piece,-and with such effect that the gun-boats dropped out of range and ceased firing.

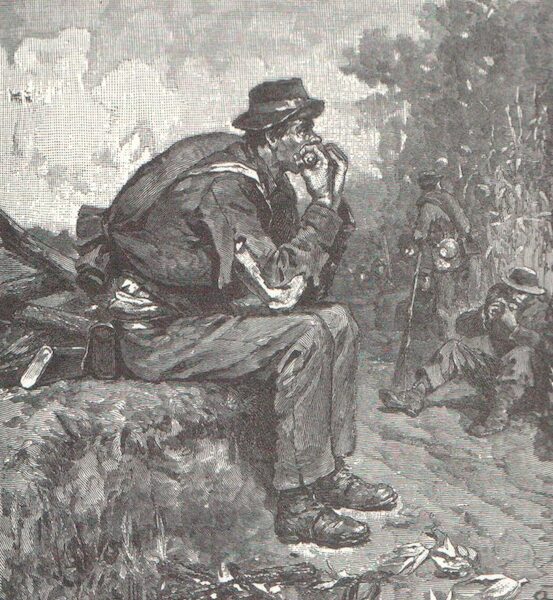

At night General Tilghamn called his leading officers in consultation-Colonels Heiman, Forrest, and drake are all that I can now recall as having been present. The Federal forces were variously estimated by us, 25,000 being, I think, the lowest. To oppose this force General Tilghamn had less than four thousand men,-mostly raw regiments armed with shot-guns and hunting-rifles; in fact, the best-equipped regiment of his command, the 10th Tennessee, was armed with old flint-lock “Tower of London” muskets that had “done the state some service” in the war of 1812. The general opinion and final decision was that successful resistance to such an overwhelming force was an impossibility, that the army must fall back and unite with Pillow and Buckner at Fort Donelson. General Tilghamn, recognizing the difficulty of withdrawing undisciplined troops from the front of an active and superior opponent, turned to me with the question, “Can you hold out for one hour against a determined attack?” I replied that I could. “Well, then, gentlemen, rejoin your commands and hold them in readiness for instant motion.” The garrison left at the fort to cover the withdrawal consisted of part of Company B, 1st Tennessee Artillery, Lieutenant Watts, and fifty-four men.

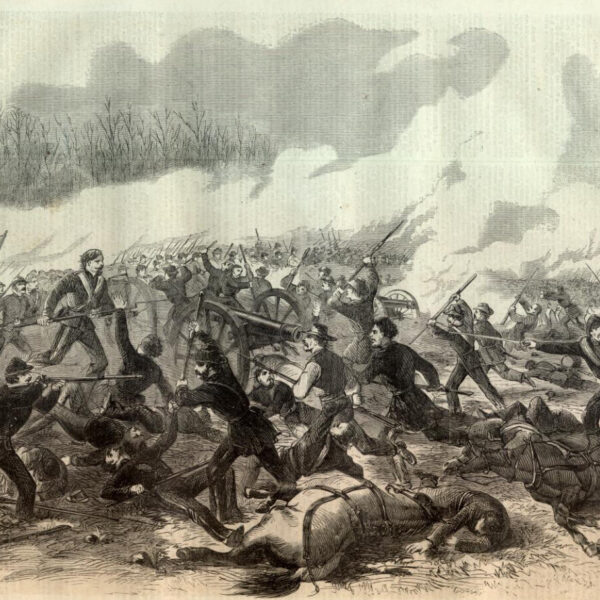

The forenoon of February 6th was spent by both sides in making needful preparations for the approaching struggle. The gun-boats formed line of battle abreast under the cover of the island. The Essex, the Cincinnati, the Carondelet, and the St. Louis, the first with 4 and the others each with 13 guns, formed the van; the Tyler, Conestoga, and Lexington, with 15 guns in all, formed the second or rear line. Seeing the formation of battle I assigned to each gun a particular vessel to which it was to pay its especial compliments, and directed that the guns be kept constantly trained on the approaching boats. Accepting the volunteered services of Captain Hayden approaching boats. Accepting the volunteered services of Captain Hayden (of the engineers) to assist at the Columbiad, I took personal supervision of the rifle. When they were out of cover of the island the gun-boats opened fire, and as they advanced they increased the rapidity of their fire, until as they swung into the main channel above the island they showed one broad and leaping sheet off lame. At this point, the van being a mile distant, the command was given to commence firing from the fort; and here let me say that as pretty and as simultaneous a “broadside” was delivered as I ever saw flash from the sides of a frigate. The action now became general, and for the next twenty or thirty minutes was, on both sides, as determined, rapid, and accurate as heart could wish, and apparently inclined in favor of the fort. The iron-clad Essex, disabled by a shot through her boiler, dropped our of line; the fleet seemed to hesitate, when a succession of untoward and unavoidable accidens happened in the fort; thereupon the flotilla continued to advance. First, the rifle gun, from which I had just been called, burst, not only with destructive effect to those working it, but with disabling effect on those in its immediate vicinity…

General Tilghman now consulted with Major Cilmer and myself as to the situation, and the decision was that further resistance would only entail a useless loss of life. He therefore ordered me to strike the colors, now a dangerous as well as a painful duty. The flag-mast, which had been the center of fire, had been struck many times; the top-mast hung so far out of the perpendicular that it seemed likely to fall at any moment; the flag hal-yards had been cut by shot, but had fortunately become “foul” at the cross-trees. I beckoned-for it was useless to call amid the din-to Orderly-Sergeant Jones, an old “man-o’-war’s man,” to come to my assistance, and we ran across to the flag-staff and up the lower rigging to the cross-trees, and by our united efforts succeeded in clearing the halyards and lowering the flag. The view from that elevated position at the time was grand, exciting, and striking. At our feet the fort with her few remaining guns was sullenly hurling her harmless shot against the sides of the gun-boats, which, now apparently within two hundred yards of the fort, were, in perfect security, and with the coolness and precision of target practice, sweeping the entire fort; to the north and west, on both sides of the river, were the hosts of “blue coats,” anxious and interested spectators, while to the east the feeble forces of the Confederacy could be seen making their weary way toward Donelson…

The fight was over; the little garrison were prisoners; but our army had been saved. We had been required to hold out an hour; we had held out for over two.

© 2025 The Civil War Monitor