The morning of May 15, 1862 set up to be another feather in the cap of the U.S. Navy following her victories at Port Royal, South Carolina (November, 1861) and the capture of New Orleans (April, 1862). Up until then, conventional naval wisdom held that heavily fortified shore batteries were superior to standard wooden vessels. However, recent Union naval victories over Confederate forts and the advent of ironclad ships offered more than just the prospect of a pyrrhic victory.1

In early May, Union naval officers developed a plan to make a run up the James River while the powerful Confederate iron-clad ram CSS Virginia lay in port for repairs. By May 8th, the Navy assembled a small task force to neutralize Rebel works along the route; however, the Virginia threatened to derail their plan. By the 11th, news arrived that the Confederates were forced to scuttle the Virginia as they abandoned Norfolk. Without the menacing ironclad to prevent Union shipping from ascending the James River, the Rebels had to scramble to fortify any waterborne approaches to the Confederate capital.2

Sensing a fleeting opportunity, Union naval officials planned to force a passage before the Confederate defenses could be completed. This sudden opening emboldened Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough to send a naval force in an attempt on Richmond itself. Potentially, the fleet would not only capture the Confederate capital but it also prevent the Navy from having to share the glory with Major General George B. McClellan whose army continued its timid advance towards Richmond. With seemingly little to hinder a run up-stream, Goldsborough ordered Commander John Rodgers to take his force of wooden and iron-clad gunboats up the James to force Richmond into surrender.3

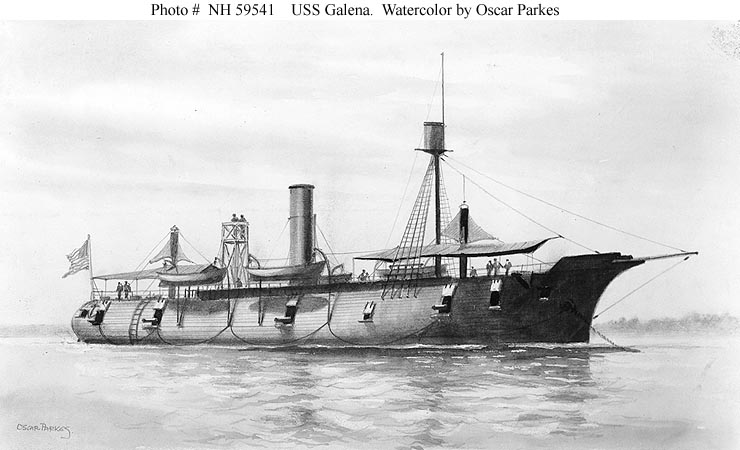

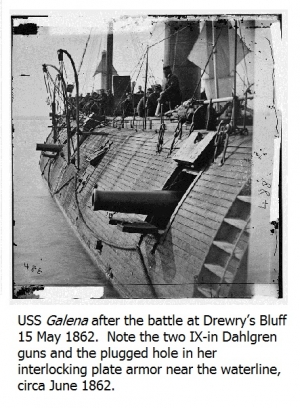

Early on May 15th, Rodgers’ five-ship task force, now reinforced by the armored gunboats USS Monitor and Naugatuck, resumed its ascent up river. Shortly, before 8 o’clock in the morning, the flotilla approached Fort Darling atop Drury’s Bluff, a high prominence located at a sharp bend in the river about 8 miles below Richmond. Soon after heavy Confederate cannon fire, which included salvaged naval guns manned by sailors from the Virginia, engaged Rodgers’ command ship, the USS Galena approached to within 600 yards of the fort. Rodgers’ ships also spotted hastily constructed obstructions in the river which prevented further progress as Confederate artillery fire grew in intensity. The Monitor anchored close to the Galena while the remaining vessels steered several hundred yards downstream.4

Early on May 15th, Rodgers’ five-ship task force, now reinforced by the armored gunboats USS Monitor and Naugatuck, resumed its ascent up river. Shortly, before 8 o’clock in the morning, the flotilla approached Fort Darling atop Drury’s Bluff, a high prominence located at a sharp bend in the river about 8 miles below Richmond. Soon after heavy Confederate cannon fire, which included salvaged naval guns manned by sailors from the Virginia, engaged Rodgers’ command ship, the USS Galena approached to within 600 yards of the fort. Rodgers’ ships also spotted hastily constructed obstructions in the river which prevented further progress as Confederate artillery fire grew in intensity. The Monitor anchored close to the Galena while the remaining vessels steered several hundred yards downstream.4

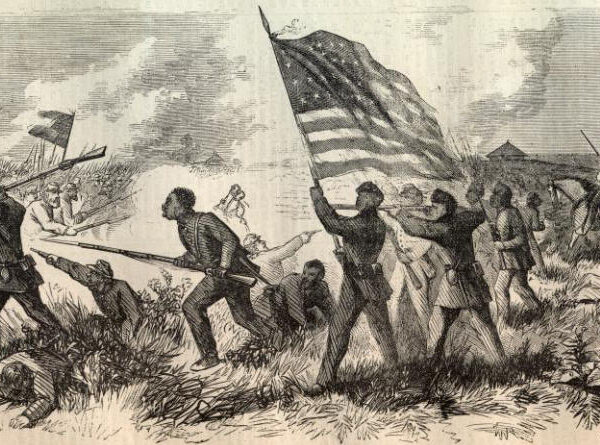

Historically, Marines fought from the fighting tops of masted sailing vessels. On board the armored, steam-driven Galena, however, the Marines remained inside the ship firing through the ship’s gun ports. A battalion of Confederate Marines commanded by Capt John D. Simms served in similar fashion; however, on this day they manned rifle pits along Drury’s Bluff, harassing Union sailors visible through the Galena’s gun ports. Sharp-shooters also opened up a “severe fire” on the lightly protected wooden gunboats, piercing their bulwarks and wounding several sailors. Rodgers’ gunboats traded salvos with the shore batteries and sent broadsides into the woods aimed at the Confederate infantry and Simms’ Marines. The 100-pounder Parrott rifle on board the Naugatuack burst, disabling the gunboat. Soon thereafter, a combination of Confederate artillery and concealed sharp-shooters compelled the remaining exposed wooden ships to retire further down river.5

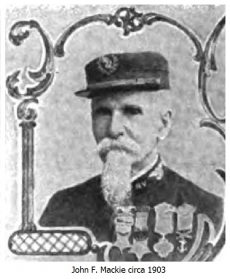

The Monitor remained close to the Galena but the Confederates chose to concentrate their fire on a more vulnerable target after several direct hits merely caromed off the Monitor‘s heavy armor. That left the Galena alone to take the full brunt of the Rebel onslaught; their salvo ripped through her armored sides. On board the Galena, Corporal John F. Mackie commanded the ship’s 12-man Marine guard. Amid the din of battle, the Marines “were at [their] ports, taking care of the sharpshooters on the opposite bank.”6

By nine o’clock, the Monitor passed the Galena in an attempt to draw some of the enemy’s fire and to engage Fort Darling; however her guns could not be elevated high enough and she withdrew close by in order to continue shelling the shore. Inside the Galena, shot and shell gashed her iron plates, sending hot metal and jagged splinters flying through her gun deck and leaving human wreckage in their wake. According to Mackie, the Galena’s smoke stack was so full of holes it looked like a giant “nutmeg grater.”7

Amid the carnage, Rodgers and his crew bravely continued to fight as the ship flew apart around them. After sustaining four consecutive direct hits, the ship staggered as shells pierced her armor and exploded between decks. As the haze cleared, Mackie saw that the entire Third Division of the four IX-inch Dahlgren guns and the 100-pounder Parrott rifle had been wiped out. He yelled to his Marines, “Come on, boys here is a chance for the marines!” Quickly, he cleared the deck and rallied the Marines who put the great gun back into action.8

Amid the carnage, Rodgers and his crew bravely continued to fight as the ship flew apart around them. After sustaining four consecutive direct hits, the ship staggered as shells pierced her armor and exploded between decks. As the haze cleared, Mackie saw that the entire Third Division of the four IX-inch Dahlgren guns and the 100-pounder Parrott rifle had been wiped out. He yelled to his Marines, “Come on, boys here is a chance for the marines!” Quickly, he cleared the deck and rallied the Marines who put the great gun back into action.8

By 11 o’clock, however, it was a shortage of ammunition that finally forced Rodgers to withdraw; he had sustained over 40 direct hits which resulted in terrific damage and dozens of casualties among the crew. The Confederates cheered in triumph atop the bluff as the battered Yankee vessels made their way back down stream. Richmond was saved and the Union Navy’s bold plan defeated. When recounting the battle, Rodgers praised the Marine effort stating, “ the marines were efficient with their muskets, and they, . . . when ordered to fill vacancies at the guns, did it well.” For his part, Mackie became the first Marine to receive the recently created Medal of Honor.

David Kummer is a Major in the United States Marine Corps and a researcher for Marine Corps University and the Marine Corps History Division.

Notes:

1. Chester G. Hearn, Admiral David Dixon Porter: The Civil War Years (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996) 68, 72

2. “Goldsborough to Welles,” 9 May 1862, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I, vol. 7 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1898), 331 (hereafter cited as ORN) “The Defiance of Richmond,” 16 May 1862, The Richmond Daily Dispatch; Thomas J. Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy from its Organization to the Surrender of its last Vessel (New York: Rogers & Sherwood, 1887), 227. (hereafter cited as Scharf, Confederate States Navy).

3. “Welles to Goldsborough,” 11 May 1862, ORN, 341; “Welles to Goldsborough,” 13 May 1862, ORN, 347; “Goldsborough to Rodgers,” 15 May 1862, ORN, 355.

4. “Rodgers to Goldsborough,” 16 May 1862, ORN, 357; Scharf, Confederate States Navy,190

5. Scharf, Confederate States Navy,716; Walter F. Beyer and Oscar F. Keydel, Deeds of Valor: How America’s Heroes Won the Medal of Honor, vol. 2 (Detroit: Perrien-Keydel Co., 1901),26-27. Hereafter as Beyer and Keydel, Deeds of Valor. “Morris to Rodgers,” 16 May 1861, ORN, 363.

6. “Jeffers to Rodgers,” 16 May 1862, ORN 362; Beyer and Keydel, Deeds of Valor. 28.

7. “Jeffers to Rodgers,” 16 May 1862, ORN 362; Beyer and Keydel, Deeds of Valor. 26,28.

8. John F. Mackie, “The Bombardment of Fort Darling,” The Story of American Heroism. J.W. Jones, ed. (Springfield, Ohio, 1897), 658. “Rodgers to Goldsborough,” 18 May 1862, ORN, 368.

Image Credits: U.S. Naval Historical Center, Library of Congress, and Deeds of Valor.