It’s hard to believe that 2014 marks the 25th anniversary of the release of the Hollywood movie Glory. Twenty-five years later it is also difficult to remember that for many Americans this was their first introduction to the story of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and the broader story of African Americans and the Civil War. More than midway through the Civil War sesquicentennial, a very different picture confronts us. The story of black soldiers is front and center in a narrative that places slavery and emancipation at the center of our understanding of what the war was about and what it accomplished. The contributions of United States Colored Troops can be seen on the big screen, in plays and musicals, news articles, museum exhibits, on National Park Service battlefields and in the textbooks we use in our schools.

The emphasis throughout the sesquicentennial on the contributions of black soldiers is part of a broader embrace of the Civil War as a “New Birth of Freedom.” The National Park Service helped to popularize it early on by framing their programs around the theme “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Within this interpretation, what started out as a war to preserve the Union was ultimately transformed into a war to end slavery. The end of legalized bondage brought the country closer to realizing its founding creed of equality for all. African-American soldiers function as the nation’s moral compass within this narrative as they faced numerous challenges ranging from racial discrimination within the ranks, unequal pay, and, on the battlefield itself, an enemy that could only view them as former slaves now engaged in servile insurrection. It’s a triumphant story of freedom that bridges the brief promise of Reconstruction, the long night of Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s and, for some, the election of the nation’s first black president.

No one will dispute that our understanding of the Civil War era is richer and more complete as a result of this increased attention to the military experience of former slaves and free blacks. But as we move into the 150th anniversary of 1864—a year in which black soldiers witnessed extensive combat—this increased attention has pushed us farther away from more fully understanding the military experience of black Americans in the Civil War.

We can see this most clearly in connection to the difficult subject of atrocities committed on battlefields involving black soldiers. New studies have emerged on the massacres of black men by Confederates at places such as Fort Pillow, Tennessee, and the Crater outside of Petersburg, Virginia. This sharp focus highlights how a growing number of Confederates viewed the war in 1864 and cuts to the core of the dangers that black soldiers faced on the road to freedom. But where in our popular understanding is there room for stories of United States Colored Troops massacring Confederates?

On June 15, 1864, “colored troops” in Brigadier General Edward Hincks’ Third Division of the Army of the James successfully stormed a line of Confederate earthworks outside of Petersburg. The assault received a great deal of attention in the press and in the ranks as well, but alongside praise of their battlefield prowess stories of the execution of prisoners spread. The Republican Tribune headed its dispatch: “The Assault on Petersburg—Valor of the Colored Troops—They Take No Prisoners, and Leave no Wounded.” The commander of the 30th USCT informed his family that the black soldiers “fought splendidly” and “took no prisoners.” One white soldier noted that “the rebs were shown no mercy.” “I saw some of them to-day,” wrote another soldier. “They said the white folks took some prisoners, but they did not.”

In one of the more graphic accounts of the battle, Chaplain Henry M. Turner of the 1st USCT emphasized that “Fort Pillow was the battle cry on both sides.” In the pages of the Christian Recorder he admitted that a few Confederates “held up their hands and pleaded for mercy, but our boys thought that over Jordan would be the best place for them, and sent them there, with very few exceptions.” Turner was not pleased with the conduct of the men. Even though he viewed it as retaliation for earlier actions by Confederates, Turner still chose to see it as “an outrage upon civilization and Christianity.”

When Confederates massacre black soldiers the latter are engaged in a desperate fight for freedom, but what happens when the roles are reversed? Our popular understanding of the war leaves very little room to understand these stories. The cycle of atrocity and vengeance reflected in these accounts and others clouds the heroic roles to which black soldiers have been assigned in the grand narrative. Failing to address these accounts results in a one-dimensional understanding of the experience of black soldiers on the battlefield.

Early in the war, Frederick Douglass insisted that once the black man was given “a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” The turn toward what some historians have called “hard war” in 1864 and early 1865 certainly tested that proposition, but it also left many white Americans sorting out their own racial assumptions related to the question of whether blacks could be controlled once they learned how to kill.

The bravery and sacrifice of black soldiers featured in movies like Glory and Lincoln has gone far to shape our own assumptions of what freedom should have meant in 1865. A closer look at the scale of violence described above, however, may help us come to terms with why military service did not translate into more lasting civil rights gains. We may even catch a glimpse of this nation’s continued struggle with race and violence.

Kevin M. Levin teaches American history at Gann Academy near Boston. He is the author of Remembering the Battle of the Crater: War as Murder (2012) and can be found online at Civil War Memory.

Sources: William A. Dobak, Freedom By the Sword: U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2011); Noah Andre Trudeau, Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War (Castle Books, 2002); John David Smith ed., Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

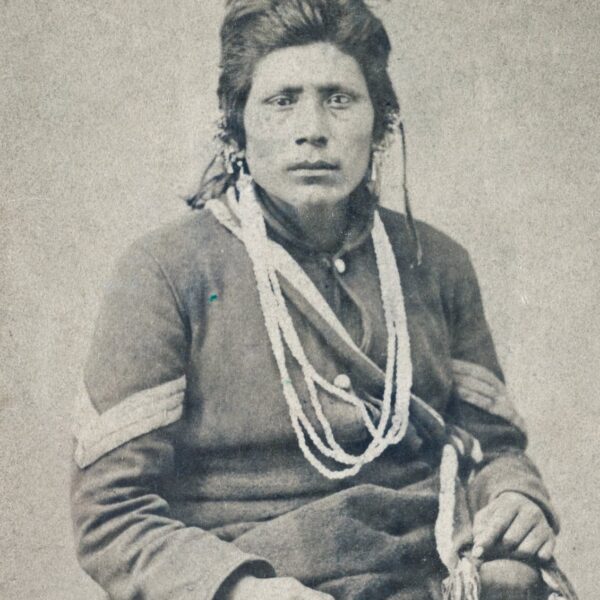

Photo Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs (loc.gov).