Brian Matthew Jordan

I suppose you could say that I started researching my recently published book, Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War, when I was 12 years old. In 1998, I met a man from my hometown of Akron, Ohio, who spent much of his late teens and early twenties crisscrossing the Midwest in search of the last survivors of Abraham Lincoln’s armies. Nearly 70 years old and the son of a World War I private, John “Gary” Dillon and I struck up a most unlikely friendship.

Though a self-effacing man of little means and few words, Gary always had plenty to say about the men he called “my veterans.” “There was an aura about them,” he explained. Gary recalled the precious days that he passed with “Uncle Dan” Clingaman of Wauseon, Ohio (who entrusted to Gary his program from the final Blue-Gray reunion in Gettysburg in 1938); his attendance at a birthday party for Alvin Smith, who served with the United States Colored Troops and recalled with precision the price he had fetched on the slave auction block; and his rail journey to Duluth, Minnesota, where he finally met his venerable pen pal Albert Woolson, who before his death at age 109 in August 1956 was the last survivor of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the largest northern veterans’ organization.

Gary pasted his snapshots of the furrowed “old boys” in three leather-bound scrapbooks, each teeming with newspaper clippings that chronicled how the GAR slowly but inexorably folded up its tents. When the time came, Gary would lovingly mount the veterans’ obituaries on subsequent pages. Before I went off to college, I spent an evening with Gary, turning once more the brittle pages of those albums that he shared with me so often. “You got the sense,” he said, “that even after so many decades, they had never really put the war behind them.”

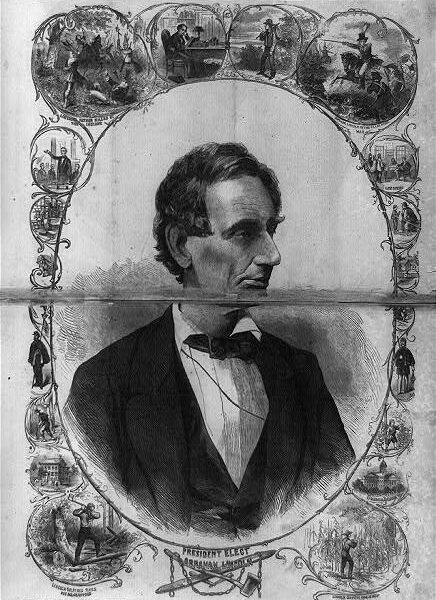

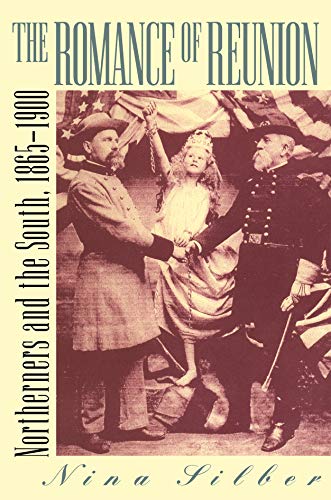

And I never really put that haunting remark behind me. As an undergraduate, it rang in my ears when I read David W. Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American

Memory(2001) and Nina Silber’s The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865–1900(1993). These books made powerful arguments that a culture of sectional reconciliation prevailed in the late 19th century, sanitizing and segregating the Civil War narrative. It made perfect sense, and yet I could never fully embrace the idea that Americans—much less grizzled veterans sporting empty sleeves—ever reached meaningful sectional accord.

As a young boy, I had maintained a steady diet of harrowing battle studies—Gordon C. Rhea’s The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5–6, 1864 (1994), Ernest B. Furgurson’s Chancellorsville 1863: The Souls of the Brave(1992), Earl J. Hess and William L. Shea’s Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West(1992), and the volumes in Gary W. Gallagher’s “Military Campaigns of the Civil War” series with the University of North Carolina Press were among my favorites—and found it too difficult to believe that the rancor of the Civil War was something easily willed away. I’d likewise never forgotten the emotional punch packed by photography historian William A. Frassanito’s haunting books Gettysburg: A Journey in Time(1975) and Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day(1978).

So it was off to graduate school—with David Blight at Yale University. He was a mentor’s mentor. If I persuaded David that his Race and Reunion did not do enough to emphasize the Union veterans who fanned the war’s embers, he (and many years of research) ultimately persuaded me that white northern civilians did indeed seek to “let bygones be bygones.” Marching Home, then, became the tale of how men who couldn’t forget lived in a society that—perhaps until my friend Gary’s generation—wouldn’t remember.

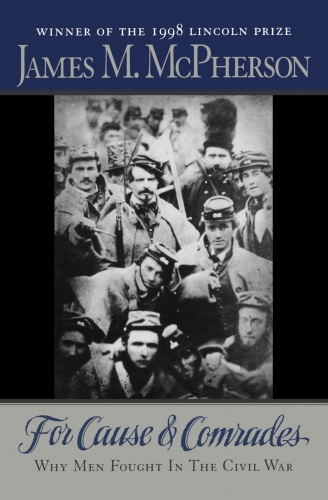

Marching Home is indebted to many books and to many historians. Readers can likely detect the influence of soldier studies like James M. McPherson’s For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War(1997), another childhood favorite and the one that perhaps opened my eyes to the power of archival sources. And yet Marching Home is most especially my effort to understand those men whom Gary Dillon described but could never explain. Rooted in research that took me to nearly 30 states, it is my own scrapbook of the Grand Army, my attempt to recover the ordinary voices of some extraordinary men. Union veterans did not abandon their cause, but were forsaken themselves by a country hurtling headlong toward the Gilded Age.

There are certain chance encounters that change your life forever. I don’t know how Gary Dillon came into my life, but I know why. A few months ago, I visited Gary at his Akron home, littered with newspapers he can no longer read. At 86, he is losing his sight—and his powers of recollection. But tears welled behind his thick lenses as I related the news that the book was finished. “The boys would be proud,” he said. I opened the book to the photograph of his old chum Albert Woolson. It took him a moment to focus. “215 1⁄2 East Fifth Street,” he suddenly belted out, recalling the veteran’s Duluth address with precision. And then we cried together.

Before long, I’ll receive that dreaded call. Before long, a man who gripped the hands of a former slave and veterans of the Union army will join them at their eternal campfire. Gary knows that the end is near, too, which is why he bundled up those scrapbooks—and Uncle Dan’s reunion program—and gave them to me.

One day I’ll donate them to an archive, so that future generations of historians can profit from them the way I have. But I’ll be holding on to them for now. Held together by string, those crumbling old albums are, above all others, the books that built me.