Undoubtedly one of the reasons for the tremendous, abiding interest Americans have with the Civil War is that a great many of us have a personal connection to it. We have uncles who fought in it, cousins who were widowed by it, or grandparents who were liberated by it. We live in towns that changed hands during the war, went to high schools named for famous generals, or help put out flags on soldiers’ graves on Memorial Day. The conflict even serves as a dubious backstory to the latest Hollywood steampunk fantasy. Perhaps even more than World War II, the legacy of the American Civil War is all around us.

Undoubtedly one of the reasons for the tremendous, abiding interest Americans have with the Civil War is that a great many of us have a personal connection to it. We have uncles who fought in it, cousins who were widowed by it, or grandparents who were liberated by it. We live in towns that changed hands during the war, went to high schools named for famous generals, or help put out flags on soldiers’ graves on Memorial Day. The conflict even serves as a dubious backstory to the latest Hollywood steampunk fantasy. Perhaps even more than World War II, the legacy of the American Civil War is all around us.

That personal intimacy with the war is a good thing, mostly, but it sometimes also lends itself to a false intimacy, an assumption that we can intuit the beliefs and motivations of those long-dead men and women. The reality is that in most cases, we haven’t got a damn clue. It’s hard enough, most of the time, to figure out what they did, much less why they did it, or what they thought about it.

Certainly there are many people from that era, men and women, soldiers and civilians, who left diaries and letters that have survived down to the present that give us real insight into their thoughts at the time. There are also those who wrote memoirs decades later; these are helpful but come with the caveat that they were written both from the perspective of the intervening years, and with the knowledge and intent that they would be read by a wide audience. The memoir depicts the old veteran as he wanted to be remembered, rather than how he actually was.

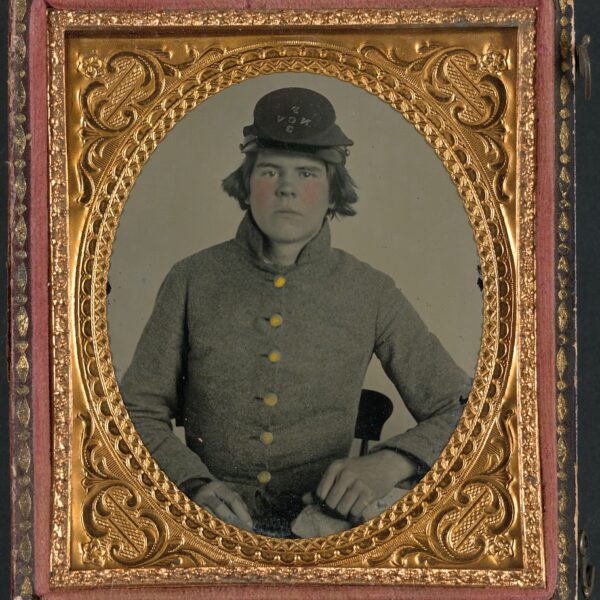

But most of us don’t have the luxury of being able to refer to a stack of fragile documents, written in rusty ink, to know why those young men eagerly marched off to war or, in some cases, scrambled for cash money to find a substitute. We do not know how their wives and mothers and children managed in their absence, or reacted when they saw their loved one’s name printed in a casualty list in the newspaper. We just do not know, and likely cannot ever know, the thoughts, inspirations and fears of these men and women.

The men who went off to war in 1861 were, like soldiers today, motivated by a whole range of reasons, often multiple reasons at once, and often by reasons that they could not fully articulate to themselves, much less to others. And while some clearly saw a larger, moral purpose to their service, many of the young men who so happily marched off to war 150 years ago did so for no reason more noble than not wanting to miss out on what looked to be the greatest adventure of their lives.

Unfortunately, that lack of documentation doesn’t stop many modern Americans from filling those gaps in their knowledge about their kin with imagined attributes and virtues. This is mostly subconscious, I suspect, originating from a deep desire to identify personally with those long-dead ancestors, to find them likeable, to see oneself in them. It’s understandable, but it’s a happy fantasy that serves the present, not the past.

I really do wish I could talk to that 20-year-old soldier, a century and a half ago, and ask him why—why was he enlisting? What motivated him? What did he expect would happen? And I wish I could talk to him again, trudging back home from Appomattox—tired, hungry, hardened, and perhaps traumatized by his experiences.

Those are questions I’d want to ask, and never can. The first principle of the historian is to recognize that there are some things he or she will never fully know. That’s a hard thing, but to my thinking, it’s preferable to projecting our own deep-seated wants and desires onto people we never met. Fantasy is no way to honor one’s ancestors.

Andy Hall is a Texan and Southerner by birth, residence and lineage, with a family tree full of butternuts. With a background in history, museum studies and marine archaeology, Hall also writes at his own blog, Dead Confederates.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress.