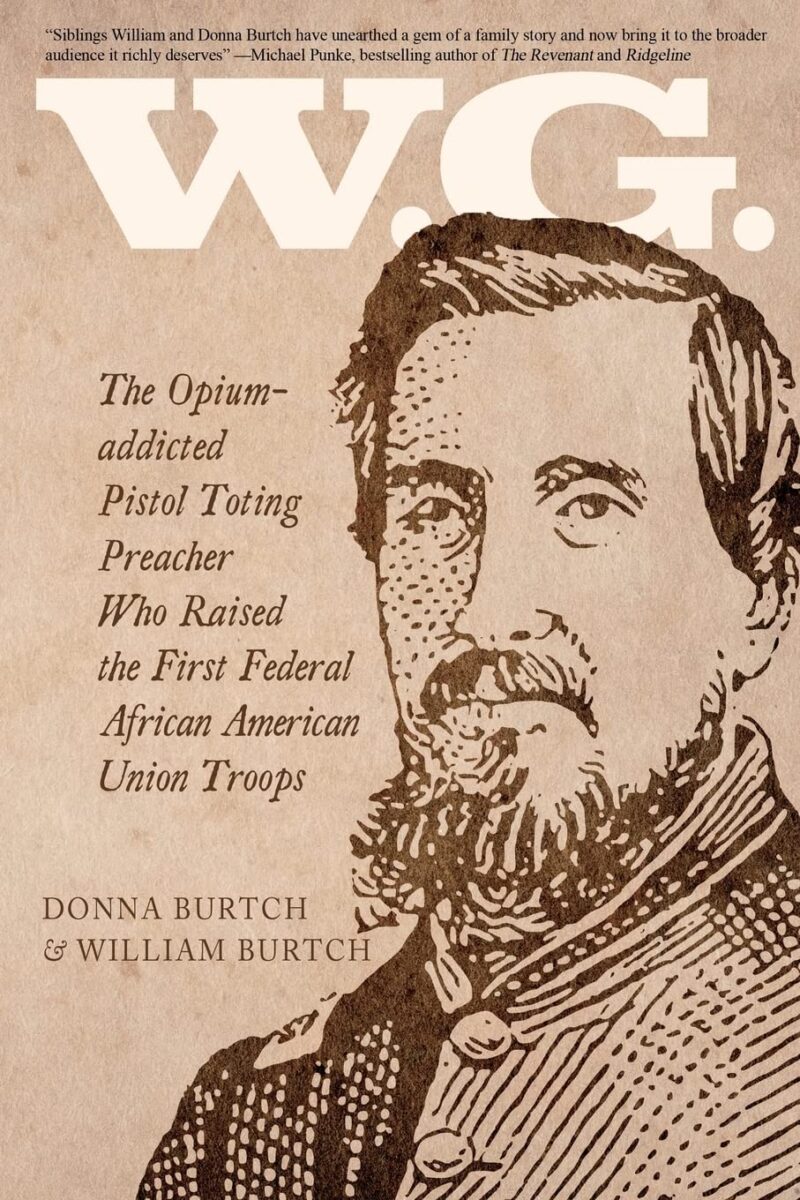

Donna and William Burtch’s W.G. explores the fascinating life of W.G. Raymond, a white Baptist preacher whose experiences included everything from service as a United States army officer in the Civil War to opium addiction and faith healing. Most notably, W.G. Raymond played a prominent role in recruiting, organizing, and funding the unit that would become the 1st United States Colored Troops. Initially commissioned as the unit’s lieutenant colonel, Raymond was replaced in his command when the War Department created the Bureau of Colored Troops; his role in raising the first federal African American is largely absent from official government records. In fact, as W.G. explains, the Committee on War Claims rejected Raymond’s involvement with the 1st U.S.C.T., pointing to this absence of official records. Based largely upon Raymond’s autobiography and scattered archival sources, the authors (who are siblings and descendants of Raymond) seek to restore W.G. Raymond’s place in the historical narrative and bring attention to his life and accomplishments.

W.G. Raymond’s life, as portrayed by Donna and William Burtch, serves as a strong example of the complexity and multi-faceted nature of Civil War soldiers, officers, and veterans. Rather than depicting Raymond as a one-dimensional figure based entirely around his Civil War service, W.G. presents a man who was deeply committed to his faith, suffered from addiction and personal loss, and battled depression and suicidal thoughts. By exposing the complicated experiences and thoughts of W.G. Raymond, the authors have rightly connected him to the histories of mental health, drug addiction, religion, and Black military service in nineteenth century America. This complexity, however, also exposes the book’s main shortcoming: a lack of historical context.

While the book is rooted in W.G. Raymond’s clearly fruitful autobiography, the authors often fail to develop the circumstances, setting, and broader meaning of Raymond’s experiences. For example, W.G. recounts a fascinating encounter between Raymond and a 107-year-old enslaved woman during his Civil War service in Maryland. According to Raymond, the enslaved woman was the mother of three children fathered by her enslaver, all of whom were sold away. After Raymond expressed surprise that the enslaver “sold his own sons,” the mother replied, “that’s nothin’” (13). While this encounter speaks clearly to the broader history of slavery and the slave trade, the authors move on from the conversation without exploring the topic. For an example on how to connect Raymond’s life to the broader historical context, the authors need look no further than their own chapter on the recruitment of the 1st United States Colored Troops. Although still deeply rooted in Raymond’s autobiography, this chapter effectively engages with secondary literature on the unit as well as Black Civil War service at large to place Raymond’s recruiting efforts within a broader narrative.

Overall, W.G. presents a fascinating character whose life reflects the complex and often troubled nature of nineteenth century America. Despite its contextual shortcomings, the book convincingly affirms W.G. Raymond’s role in recruiting the 1st U.S.C.T., and provides a useful figure for further historical analysis.

Brian Martin is a doctoral student in the Department of History at The University of Alabama. His scholarship is exploring the impact of race and ideas of racial difference on the medical treatment of Black soldiers during the Civil War.