On July 21, 1861, Union and Confederate forces clashed just north of Manassas, Virginia, in the war’s first major land battle. The engagment brought together inexperienced northern and southern volunteers, most of whom expected a quick, relatively bloodless, and decisive victory. The result was a battle whose outcome remained up in the air until a late Confederate push that broke the Union army’s will to fight on … and resulted in its hasty retreat. Of the approximately 36,000 troops engaged that day, some 5,000 were killed, wounded, or declared missing. In the days after the battle ended, artists began creating scenes of the fighting and its aftermath. Shown here is a sample of some of that work.

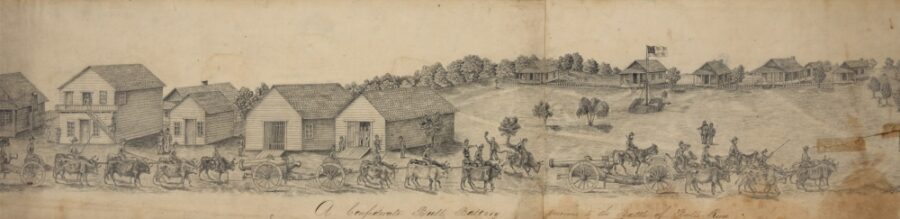

An unknown artist made this sketch of a Confederate artillery battery leaving camp to move into position before the battle. (Library of Congress)

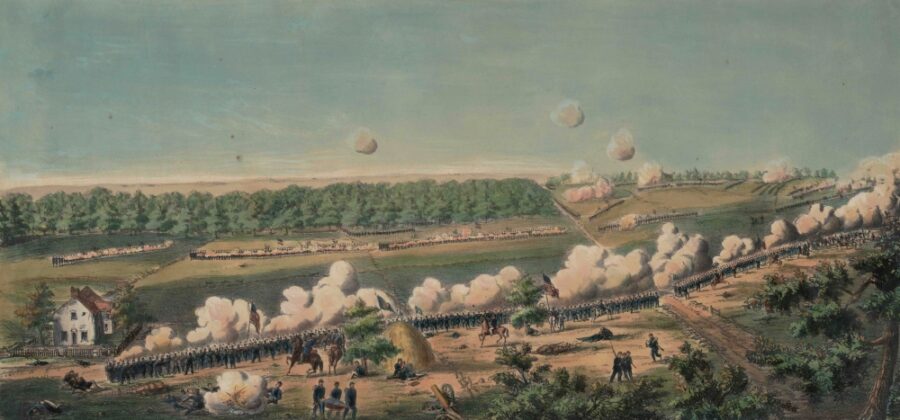

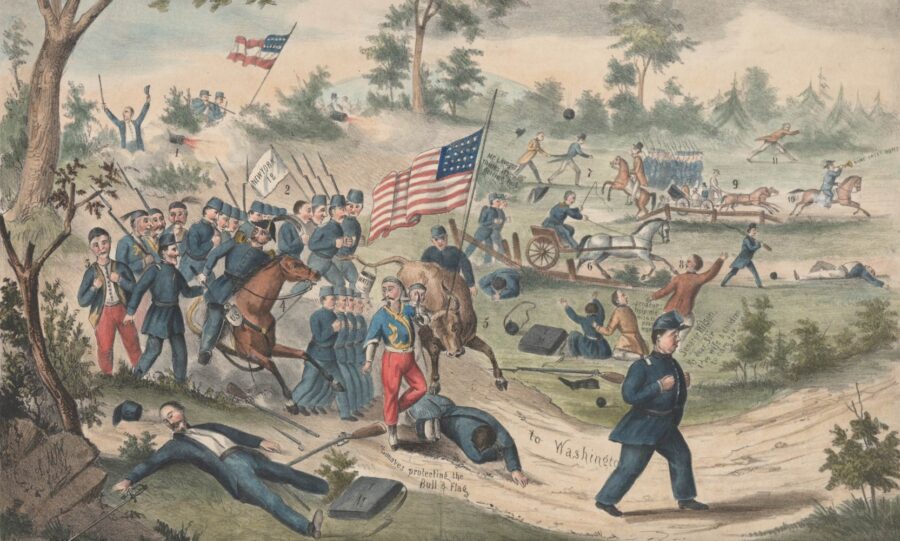

Advancing Union forces enjoyed success early in the battle, pushing Confederates from their position on Matthews Hill southward, to Henry House Hill. Among the troops that forced the Confederates back were those commanded by Ambrose Burnside, whose men are shown in action in this color lithograph. (Anne SK Brown Military Collection)

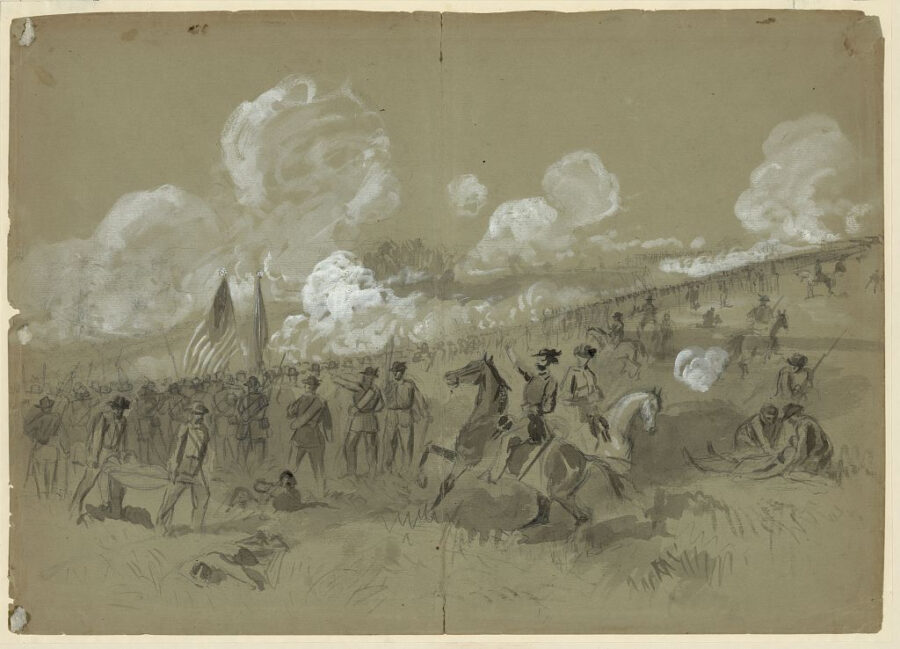

Artist Alfred Waud captured Burnisde’s men in action in this sketch made at the time of the fighting. (Library of Congress)

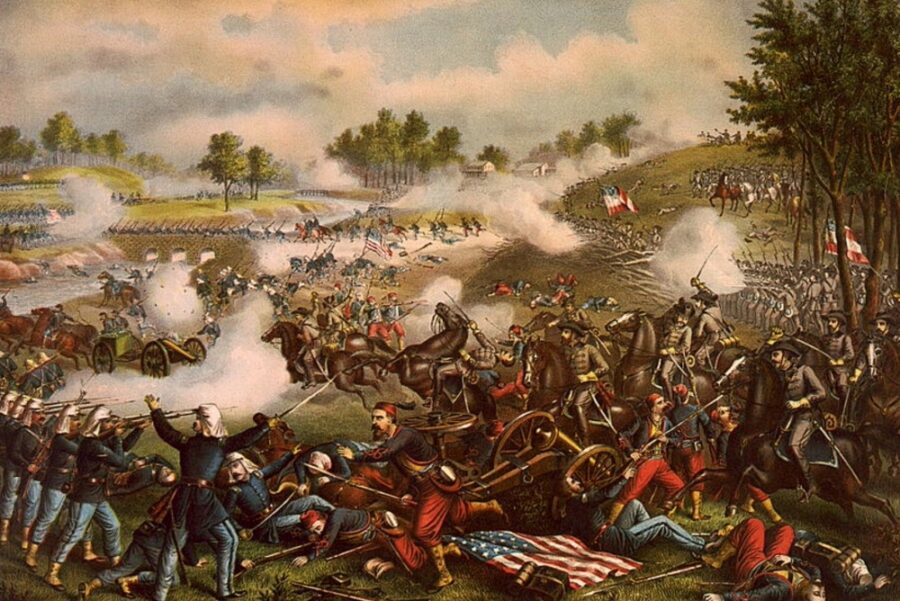

Advancing Union troops pressed the attack against the Confederates, sending more troops southward toward the heights of Henry House Hill, as depicted in this painting by Kurz & Allison. (Library of Congress)

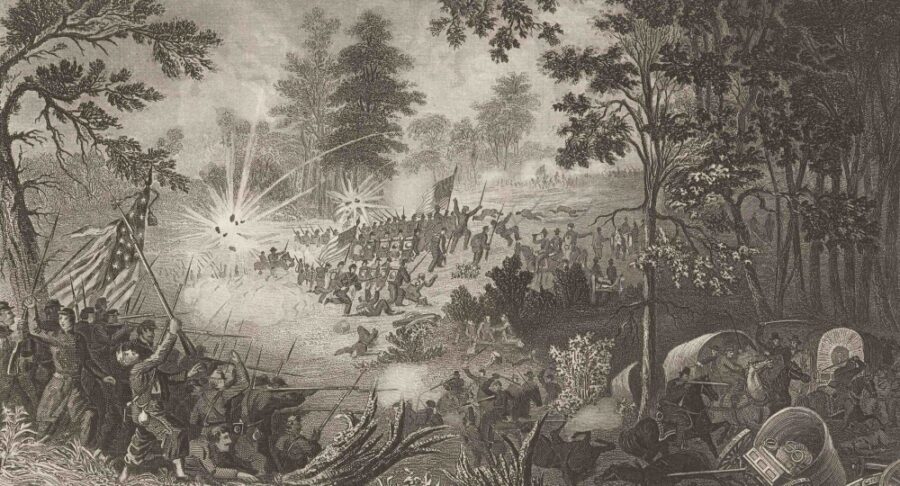

Artist Wilhelm Momberger depicted a similar scene in this postwar engraving. (Anne SK Brown Military Collection)

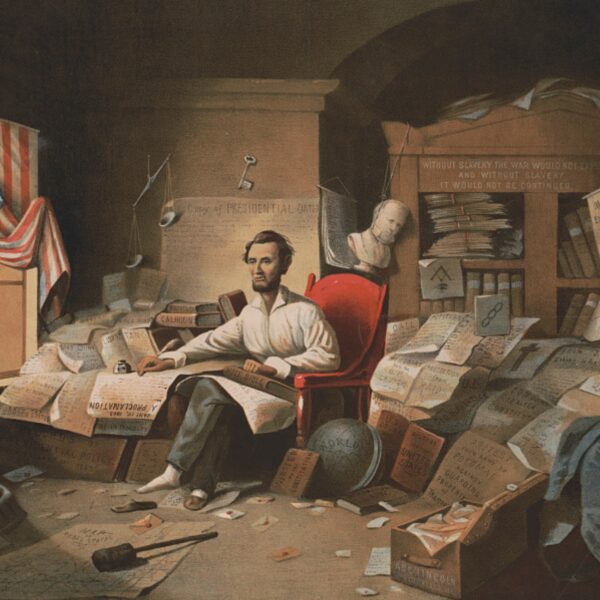

Around noon, Confederate reinforcements under Thomas J. Jackson fortified the heights of Henry House Hill. For his subsequent conduct at the battle, Jackson would earn the sobriquet “Stonewall.” Jackson is depicted here surveying the battle in a painting by H.A. Ogden. (Library of Congress)

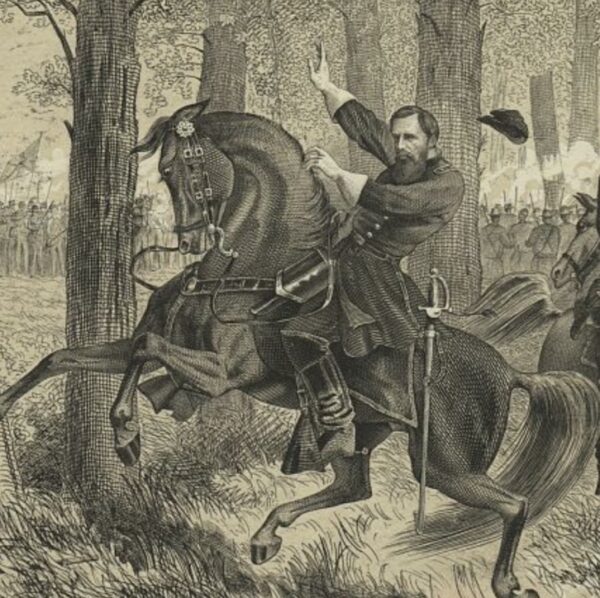

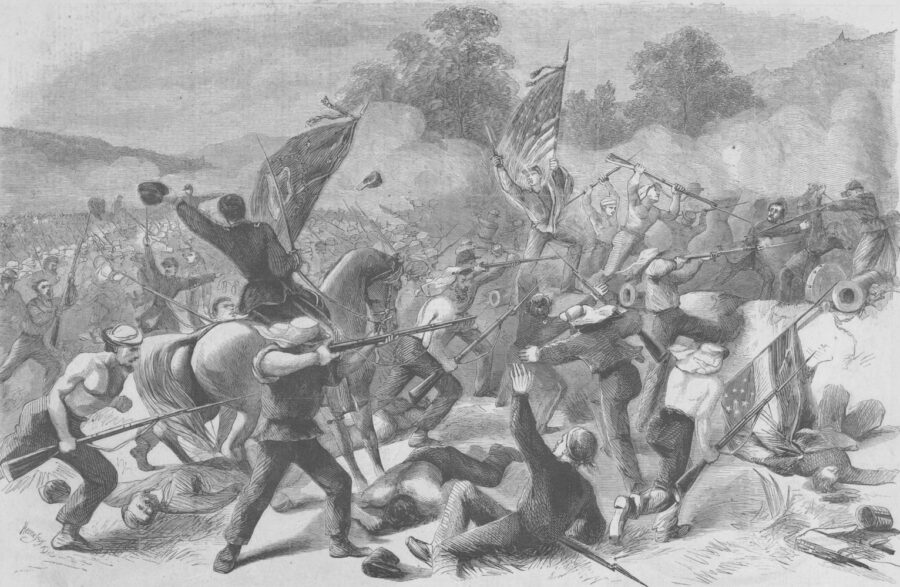

Among the Union troops who attacked up Henry House Hill were the men of the Irish 69th New York, led by its colonel, Michael Corcoran. This wartime illustration by Currier & Ives depicts Corcoran, on horseback, leading the 69th in a “desperate and bloody charge.” (Library of Congress)

Harper’s Weekly published its own rendition of the 69th New York’s advance within a few week’s of battle’s end. (Harper’s Weekly)

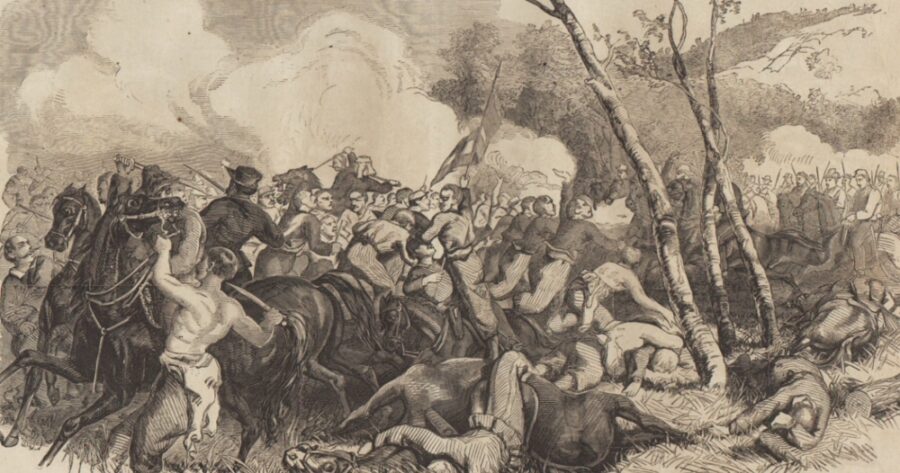

A turning point in the afternoon’s fighting occurred when Confederate infantry and cavalry attacked Union artillerists positioned at the southern end of the Union line, which were guarded in part by the 11th New York Infantry, Elmer Ellsworth’s famous unit of “Fire Zouaves.” (Anne SK Brown Military Collection)

This postwar painting by Henry Alexander Ogden shows Confederate cavalrymen overruning a Union artillery position during the afternoon of July 21, 1861. (Anne SK Brown Military Collection)

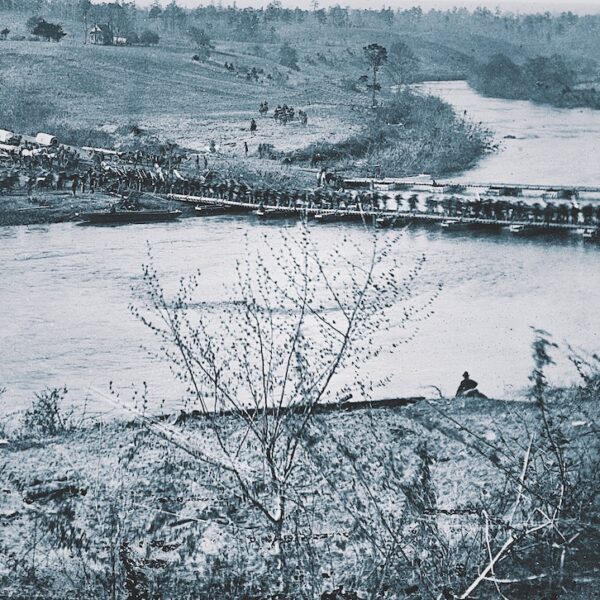

Around 4 p.m., the Confederates, recently reinforced, began to advance across the line, pushing Union troops back toward Bull Run, over which they had crossed that morning en route to the battlefield. Shown here is F.O.C. Darley’s depiction of Confederate infantry forcing Union troops to pull back. (Library of Congress)

The retreating Union forces soon disintigrated into a disorganized mob—one that swept up many northern civilians who had previously arrived to view the battle from a distance—as it made its way toward the safety of Washington, D.C. The battle did not, as both sides had hoped before it began, bring a swift end to the war, which would rage for four years and costs hundreds of thousands of northern and southern lives. (Anne SK Brown Military Collection)