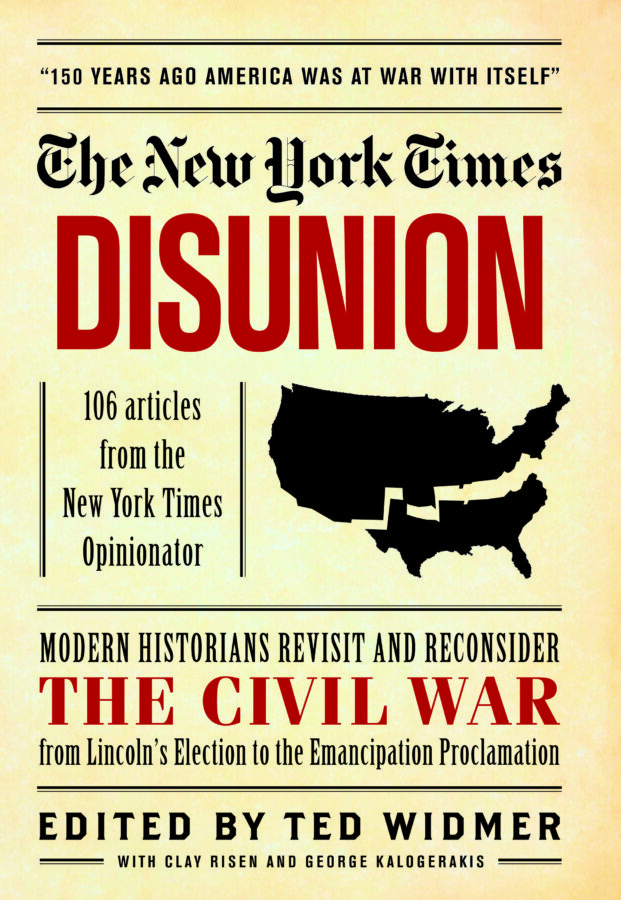

The New York Times: Disunion: Modern Historians Revisit and Reconsider the Civil War from Lincoln’s Election to the Emancipation Proclamation edited by Ted Widmer with Clay Risen and George Kalogerakis. Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, 2013. Paper, ISBN: 1579129285. $27.95.

In the fall of 2010 The New York Times marked the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s election and the commencement of the Civil War by launching “Disunion,” a daily feature on its “Opinionator” blog. Contributors were to be established authorities, some of them academics, others popular writers, all of them eminently qualified for their task, which was to provide insightful and engaging essays of about 1500 words on the conflict and its legacies, but with, in Ted Widmer’s words, “some of the snap, crackle and pop of lively online writing” (xii). This volume, edited by Widmer and two associates, includes 106 essays, about 1 in 8 of the contributions originally posted on the blog between October 31, 2010, and December 27, 2012, and covers the war more or less in sequence from the eve of Lincoln’s election to the eve of his signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. The editors’ job could not have been easy. An awful lot of good essays had to be excluded to produce an anthology that forms a cohesive narrative of the war’s first half.

In the fall of 2010 The New York Times marked the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s election and the commencement of the Civil War by launching “Disunion,” a daily feature on its “Opinionator” blog. Contributors were to be established authorities, some of them academics, others popular writers, all of them eminently qualified for their task, which was to provide insightful and engaging essays of about 1500 words on the conflict and its legacies, but with, in Ted Widmer’s words, “some of the snap, crackle and pop of lively online writing” (xii). This volume, edited by Widmer and two associates, includes 106 essays, about 1 in 8 of the contributions originally posted on the blog between October 31, 2010, and December 27, 2012, and covers the war more or less in sequence from the eve of Lincoln’s election to the eve of his signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. The editors’ job could not have been easy. An awful lot of good essays had to be excluded to produce an anthology that forms a cohesive narrative of the war’s first half.

Lincoln figures prominently in the story that emerges. He is the only figure present throughout the book. For nothing and no one else, save the war itself, do the snapshot essays form a moving picture. The slaves also figure prominently, but as a collectivity, and as part of Lincoln’s story. The South is very much neglected. Lincoln visits his stepmother before making his way to Washington, and once there, sits for photographer Matthew Brady. Mark Twain travels north, up the Mississippi River on the last civilian steamboat to do so until war’s end. Harriet Tubman leads her final exodus along the Underground Railroad to freedom. Frederick Douglass hopes for war but fears Lincoln will back away from the prospect. James Buchanan urges Congress to attempt one more compromise. Everyone waits to see what the South will do, but until the attack on Fort Sumter, we do not really see the South or its leaders do anything. Big things are happening down there, but readers are no more privy to them than Lincoln was. Only William W. Freehling’s essay on George Wythe Randolph, Thomas Jefferson’s youngest grandson, explores the motives and decisions of a secession convention participant. After the attack on Fort Sumter, Elizabeth Brown Pryor explains more than most readers will know about Robert E. Lee’s anguished decision to support the Confederacy, based on a recently discovered letter written by the general’s daughter. One wishes for more on what other southerners were thinking, fearing, hoping for, and doing, especially those southerners who orchestrated disunion and confederation.

There is an air of inevitability to the history told here, which is unfortunate. The United States prevailed because they had Lincoln, because slavery was indefensible, and because the Confederacy was unable to, in Widmer’s words, “prosecute a major war and build a domestic state.” (That the Confederacy was unable to prosecute a major war would have come as news to Lincoln.) Against this air of inevitability Edward Ayers’ essay on the First Battle of Bull Run, or First Manassas, shines. “We need to imagine immense confusion,” he writes, “with mistakes and failure and brilliance and bravery all swirled together” (170). There was nothing inevitable about the outcome of this battle, and it was just the beginning. Nor is there anything inevitable about historical evaluation even after a century and a half. For Widmer the battle was a “strategic draw,” while for Ayers it was “understood north and south as a United States defeat.”

Differences in scholarly opinion are present throughout the volume, and are responsible for much of its snap, crackle, and pop. For example, Striner’s essay on Lincoln’s audacity in late 1861, regarding slavery in Delaware, is countered by Michael Fellman’s essay on Lincoln’s trepidation regarding slavery in Missouri. Striner writes of Lincoln’s “crafty” politics, while Fellman writes of Lincoln’s “great conservatism.” It’s not that one view is right, the other wrong. It is that very little if anything was inevitable about the Civil War, which is, of course, why historians debate it and readers return to it endlessly. After all the entries on humor, new technologies, photography, regimental mascots, and all the readying and politicking, comes Winston Groom’s long essay on the bloodbath at Shiloh, which was so full of accidents, and the war has indeed begun. After Shiloh, one reads the rest of the book very differently, with less patience for the fluff of history, and with more hunger to understand what the killing accomplished. The Emancipation Proclamation, explained by David Blight in an essay written especially for this volume, offers an answer.

Some essays are real gems: Ayers’ on Manassas, Fellman’s on Sherman, and Groom’s on Shiloh to name only three. Many readers will look for and find familiar episodes in the book, for example, the battle between the Merrimack and the Monitor. Many who consider themselves well versed in the history of the war will be surprised at how much they learn, for example, about Sherman’s battles with depression, which nearly kept him on the sidelines but which ended up placing him on the field at Shiloh. There is enough trivia to sustain thousands of conversations between strangers on airplanes, on subjects ranging from underwear and its making, wearing, and cleaning, to the short life of the United States Army’s Camel Corps. There are essays on the profoundly consequential, the great battles, the momentous decisions, and the accidents that changed everything. And it is all here in easy to digest chunks—perfect for bedtime reading—that will engage readers from scholars well versed in the subject to first-timers.

Christopher Morris is a Professor of History at the University of Texas at Arlington.