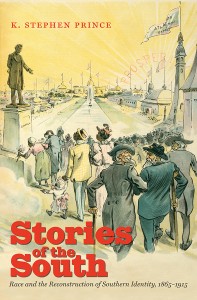

Stories of the South: Race and the Reconstruction of Southern Identity, 1865-1915 by K. Stephen Prince. University of North Carolina Press, 2014. Cloth, ISBN: 1469614189. $39.95.

In Stories of the South: Race and the Reconstruction of Southern Identity, 1865-1915, K. Stephen Prince dissects the tremendous power of stories and narratives that offered Americans new ways to imagine the South in the post-Civil War era. As Prince explains, both white northerners and southerners participated in the making and disseminating of these tales — some of which appeared in the form of actual fiction (novels, short stories, and minstrel performances), and some of which appeared in the form of scholarship and journalism — but all of which contributed to an imagined depiction of the South that had serious political consequences. These tales focused on a wide range of topics, including the travails of the Reconstruction era, the trope of the interfering Carpetbagger, the economic progress of the New South, the supposed deterioration of the black race, and the white South’s alleged superiority in racial knowledge. Throughout, Prince maintains that these stories (although challenged at every turn by African American writers and activists) exerted a commanding political influence that ultimately dissuaded northerners from intervening in Southern racial practices and allowed them to accept the long retreat from Reconstruction-era racial democracy.

In Stories of the South: Race and the Reconstruction of Southern Identity, 1865-1915, K. Stephen Prince dissects the tremendous power of stories and narratives that offered Americans new ways to imagine the South in the post-Civil War era. As Prince explains, both white northerners and southerners participated in the making and disseminating of these tales — some of which appeared in the form of actual fiction (novels, short stories, and minstrel performances), and some of which appeared in the form of scholarship and journalism — but all of which contributed to an imagined depiction of the South that had serious political consequences. These tales focused on a wide range of topics, including the travails of the Reconstruction era, the trope of the interfering Carpetbagger, the economic progress of the New South, the supposed deterioration of the black race, and the white South’s alleged superiority in racial knowledge. Throughout, Prince maintains that these stories (although challenged at every turn by African American writers and activists) exerted a commanding political influence that ultimately dissuaded northerners from intervening in Southern racial practices and allowed them to accept the long retreat from Reconstruction-era racial democracy.

Prince marshals a vast array of evidence and makes a convincing case for the persuasive power of many of these Southern stories. He insightfully traces, for example, the emergence of the trope of the terrible carpetbagger, a symbol that not only seized the imagination of white southerners but also (increasingly) white northerners, who saw in this figure an argument for ending federal involvement in Southern politics. Even African-Americans, says Prince, often accepted the portrait of carpetbagger meddlesomeness, as late as the beginning of the twentieth century. In a particularly effective chapter, Prince explores the devastating stories southern whites began to tell about race in the late nineteenth century —stories about black regression and bestiality as well as about the presumed innate knowledge white southerners possessed about race matters —that helped pave the way for the Jim Crow era, and for northern acquiescence to that process.

Prince does an excellent job showing how much culture served politics and, to some extent, vice versa. Some readers might bemoan his lack of attention to political and ideological differences among white southerners, say between conservative and radical racists. Nor is he primarily interested in correlating stories about the South with specific political rulings and pronouncements such as Supreme Court decisions or Congressional votes. Rather, Prince paints the period with a broader brush-stroke, analyzing the kinds of overarching narratives to which many people, even those with political differences, contributed, and how those narratives could shape a world view that made the politics of Jim Crow ultimately seem not only acceptable but necessary.

Prince does not ignore African American attempts to shape their own “stories of the South,” and he gives sustained attention to the writings of Charles Chesnutt, Ida B. Wells, and Pauline Hopkins, who countered notions of black regression. He also documents the work of performers, like the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who sought to musically rebut the idealized visions of plantation fiction with their mournful songs of slavery. Yet, as Prince demonstrates, African Americans were frequently stymied in their responses — a point made apparent in the way the Fisk Singers found themselves continually heralded as another black minstrel troupe.

With this book, Prince hopes to challenge what he calls “the reunion model” (9) that he says has dominated the historical scholarship on the post-Civil War era. This includes work by David W. Blight (Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory) and by this reviewer as well (The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865-1900). Like a number of recent scholars, among them Natalie Ring (The Problem South: Region, Empire, and the New Liberal State, 1880-1930) and Caroline E. Janney (Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation), Prince believes late nineteenth century sectional reconciliation was far more tenuous than what the reunion framework conveys. And, although Prince concludes his book with a tale of reconciliation in his final discussion of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, he argues that the path to reunion “proved contingent, complicated, and endlessly contested” and that “rather than a reunion of two estranged regions, the postbellum decades witnessed the construction of a new South and a new nation” (249). Yet this reviewer cannot help but worry that the “reunion model” is being too hastily discarded. Perhaps Prince’s work would be better served if he treated “the reunion model” not as something that has “blinded” historical scholarship, but as yet another influential narrative that, while it certainly competed with the kinds of stories that Prince documents, also exerted its own powerful influence at every step in the political and cultural history of the late nineteenth century. Surely, when white southerners crafted their stories about “the New South” or about northern interference on racial matters, they also had in mind the story of reconciliation that was being played out, repeatedly, in the pages of magazines, postwar fiction, travel writing, and even on the minstrel stage.

Indeed, one of the most powerful stories white southerners may have created, out of the many tales that Prince considers, was the idea of “the New North.” According to Prince, the “New North” narrative argued that northerners needed to relinquish their sectional hostilities and “accept the New South on its own terms” (120). Yet it seems, too, that the commanding trope of reconciliation played its own part in constructing the idea of “the New North” by regionalizing the qualities of interventionism, racial egalitarianism, and Civil War bitterness. Rather than consider post-war politics in terms of the relationship between the nation state and the southern states, the tale of “the New North” helped to construct an image of two sections, shaped by their own distinctive regional qualities — two sections that could come together and neatly close the circle in a well-crafted story of reconciliation.

Nina Silber is Professor of History at Boston University and author of The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865-1900.