Hurricane from the Heavens: The Battle of Cold Harbor, May 26-June 5, 1864 by Daniel T. Davis and Phillip S. Greenwalt. Savas Beatie, 2014. Paper, ISBN: 978-1611211870. $12.95.

“I have always regretted,” Ulysses S. Grant wrote in his memoirs, “the last assault at Cold Harbor was made.” He continued, “No advantage was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained” (97). One hundred and fifty years later, that battle remains largely misunderstood, thought by many to be simply a foolhardy, headlong Union dash against impenetrable Confederate earthworks. Hurricane from the Heavens: The Battle of Cold Harbor, May 26-June 5, 1864, by Daniel T. Davis and Phillip S. Greenwalt, looks to correct this impression. The book is the latest installment in Savas Beatie’s Emerging Civil War Series, which seeks to provide an introductory account of battles that can be read either in a living room or on the battlefield.

“I have always regretted,” Ulysses S. Grant wrote in his memoirs, “the last assault at Cold Harbor was made.” He continued, “No advantage was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained” (97). One hundred and fifty years later, that battle remains largely misunderstood, thought by many to be simply a foolhardy, headlong Union dash against impenetrable Confederate earthworks. Hurricane from the Heavens: The Battle of Cold Harbor, May 26-June 5, 1864, by Daniel T. Davis and Phillip S. Greenwalt, looks to correct this impression. The book is the latest installment in Savas Beatie’s Emerging Civil War Series, which seeks to provide an introductory account of battles that can be read either in a living room or on the battlefield.

In keeping with this approach, Davis and Greenwalt organize chapters around particular sites. Driving directions bring the reader to this site and the authors provide a brief – usually about ten pages – narrative of the action. The focus is on the terrain and the tactics, and the text is enlivened with quotes from unnamed common soldiers and the reports of generals.

The authors give serious attention to preliminary actions of the campaign, including Haw’s Shop, Totopotomoy Creek, and Bethesda Church. Here they demonstrate Grant’s capacity for maneuver rather than frontal assaults. Still, the casualties and frequency of combat became unparalleled, and the use of earthworks evolved rapidly. Union General John Gibbon recalled, “A few hours were all that were necessary to render a position so strong by breastworks that the opposite party was unable to carry it …” (33). An officer in the VI Corps wrote, “Great is the shovel and spade …. I would as soon dig the Rebels out than fight them” (31). As marches halted, soldiers immediately began entrenching. This discussion, coupled with the authors’ analysis of the importance of crossroads in Civil War campaigns, builds to the carnage at Cold Harbor.

Davis and Greenwalt pay fitting attention to the June 1st fighting at Cold Harbor – the “hurricane from the heavens” that gives the book its title – as the two armies jockeyed for position. However, their discussion of the attack of the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery lacks context. While they quote Confederate General Thomas Clingman as saying the Nutmeggers “had on apparently new uniforms,” there is no discussion that this engagement, in which the unit lost hundreds of men, was its first combat experience.

The major assaults of June 3rd and the brief breakthrough by elements of Francis Barlow’s division are appropriately recounted. The authors estimate that the day’s fighting resulted in approximately 4,000 Union casualties. As to why federal troops were thrown at such strong earthworks at all, Davis and Greenwalt argue that “the assault, if properly supported, could spell an end to the fighting and quite possibly, the war. Grant had to try ….” (78). Also interesting is the discussion about the semantic jousting between Grant and Robert E. Lee over the former’s desire for fighting to cease so that the wounded could be brought in, and the political price to be paid by the North in using a traditional flag of truce.

In the final chapter, Davis and Greenwalt make important analytical points about the broader campaign, arguing that Grant was “stymied” as much by the evolution of field fortifications and his “inability to exploit hard-won advantages” as by Lee’s army (107). The authors also suggest that in moving away from Cold Harbor and crossing the James River to the rail hub of Petersburg, Grant looked to avoid future frontal assaults in favor a strategy similar to that being employed in William Tecumseh Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign.

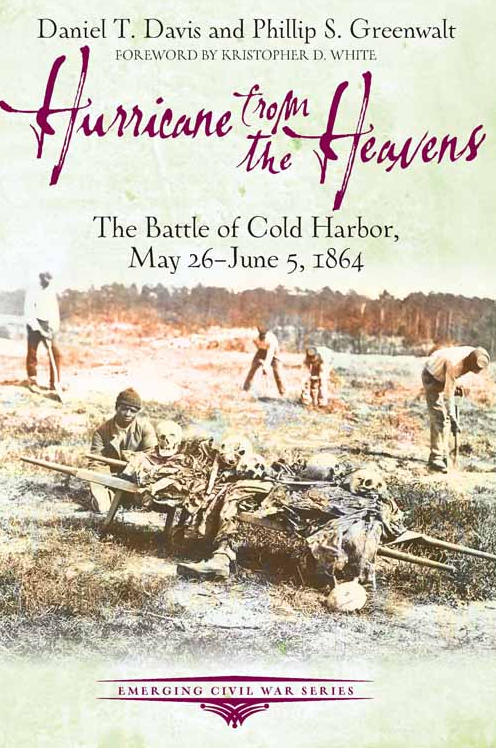

Davis and Greenwalt supplement their text with a combination of historic photographs/drawings, fine modern photographs, and battle maps. A particularly interesting feature of the book is the impressionistic asides they employ to put the reader in the mindset of the soldiers: “The first sound that greets you are the cries of the many Union wounded lying in the plain to your front” (91).

Noteworthy also are the five appendices, which feature essays and a tour of historic sites in Richmond. Two stand out. In “The Road to Cold Harbor: The Overland Campaign in Context,” Shawn Woodford concisely lays out the political considerations that hamstrung both Grant and Lee. Lincoln, Woodford argues, needed a military victory to solidify public support for the 1864 election. However, he forbade Grant from campaigning on the line of the James River, even though the general-in-chief believed that was the “most logical course of action” (116). To do so would have been to admit that Lincoln’s political opponent, George B. McClellan, had been strategically correct in his 1862 Peninsula Campaign. Meanwhile, as Grant concentrated Union forces in Virginia against a common objective, Confederate President Jefferson Davis rejected Lee’s calls for concentration in the early spring of 1864. Instead, Davis opted to use disparate forces to carry out smaller-scale operations like those against Plymouth, North Carolina. Woodford argues that if “Lee had been provided in April or early May with the extra men he actually received in late May and June, the chances of his spoiling Grant’s attack or fighting it to a standstill north of Richmond would have been considerably greater” (122).

In “Cold Harbor in Memory,” Greenwalt and Chris Mackowski draw a parallel between the negotiations over a flag of truce and Lost Cause interpretations of the battle. Lee, in seeking to maneuver Grant into admitting Cold Harbor was a defeat, and Lost Cause writers, in focusing on the butchery of Grant’s failed frontal assaults, both looked to divert attention away from the larger reality of Cold Harbor. Grant was on Richmond’s doorstep; “he lost the battle that day, but he was winning the campaign” (145).

The Emerging Civil War Series strives to provide “compelling, easy-to-read overviews” of Civil War battles and issues. Hurricane from the Heavens succeeds in doing this for one of the war’s most brutal engagements.

Peter C. Vermilyea is Lecturer in History at Western Connecticut State University. His work has appeared in Gettysburg Magazine and American History.